Why Iraqis are still searching for a 'homeland' 20 years after US invasion

The US invasion of Iraq succeeded in toppling the Baathist regime of President Saddam Hussein, but 20 years on, it clearly failed to achieve its proclaimed goal of bringing freedom, security, democracy, and prosperity to Iraq and its people.

Rather, it created a whole new set of problems. It imposed structures and institutions that are neither representative nor effective; it deepened human insecurity and introduced other kinds of instability; and it denied the prospect of long-term sustainable socio-economic development.

In other words, it created structural deficiencies and systemic impediments that shackled and denied the transformative capabilities of the Iraqi people.

The disastrous outcome of the US invasion is hardly a coincidence

Meanwhile, the human toll and suffering only increased, with hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties, and over 9.2 million Iraqis internally displaced or made refugees abroad.

The civil and political demands and aspirations of the Iraqi people remain unfulfilled and, to a large extent, were denied by design. The post-2003 structural arrangements in Iraq (also flawed by design) debilitated and weakened state institutions largely due to the dominance of political factionalism instead of participatory inclusive approaches to governance.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

State institutions were captured by political factionalism, and transformed into mechanisms that served the economic interests of the ruling elite, rendering the state largely dysfunctional and unable to deliver basic services.

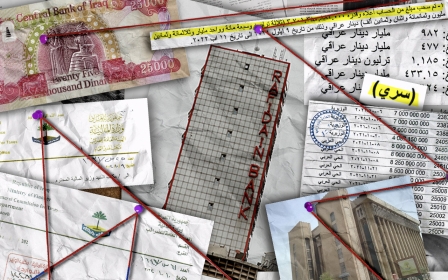

For instance, between 2003 and 2013, not a single new hospital or power plant was built, according to observers and analysts, despite spending $500bn in public funds. During the same period, Iraqi officials confirmed that $300bn was actually paid to contractors for projects that were never completed.

In 2021, the Iraqi president declared that Iraq had lost $150bn since 2003 due to embezzlement and endemic corruption - especially in the oil sector - as those billions had been smuggled out of the country.

Doomed to fail

The disastrous outcome of the US invasion is hardly a coincidence.

In the initial phase, external interventions did not include anticipation of any future developments or rebuilding and strengthening institutions, and were largely devoid of considerations for governance or accountability. Yet, these circumstances led to the present situation.

Neither the formation of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) or the Iraqi Governing Council (IGC), nor the processes that led to the new 2005 constitution, aimed to put the people and their needs at the core of the political system. It failed to create an inclusive participatory political system or establish the foundations of transparency and accountability - key pillars for any successful democratic transition process.

Fast forward to 2019 and beyond, the October (Tishreen) Protest Movement emerged as a result of cumulative governance failures that accompanied the mandates and programmes of consecutive Iraqi governments. These governance failures have their roots in the structural framework put in place during the initial phase following the 2003 invasion.

Despite the cosmetic and technical changes, the root causes of the failures were left unaddressed, or remained in the hands of particular ethno-sectarian groups who were neither interested nor able to tackle these issues as that would shake and hamper their dominance.

This explains why many governance issues that emerged after 2003 remain unaddressed due to the lack of effective and responsive institutions or mechanisms to do so.

Hence, the slogan "we want a homeland" emerged as a key demand and slogan of the October 2019 protest movement that captured the desire and need to institute fundamental changes in structures, institutions, and political processes.

Twenty years after the invasion of Iraq, the Iraqi people continue their search for a homeland.

Consequently, repeated calls over the past two decades to halt violence, address security gaps, and reform institutions to root out endemic corruption ingrained in the political system have been ignored. The people have also suffered from inadequate public services and soaring unemployment (36 percent amongst youth), amidst several other challenges.

An external intervention paradigm fraught with tensions and contradictions was bound to have such detrimental consequences, as it is inherently designed to serve the political elite, occupying forces (and by extension their allies and economic enterprises), and some regional actors, but not the Iraqi people.

Structural failures

Four elements are particularly acute in explaining these structural failures. First, ethno-sectarian identity was institutionalised as the basis of political representation, illustrated in the "muhasasa ta'fiya" quota system.

Second, the lack of agreement over fundamental issues such as federalism proved to be highly problematic. The relations between the federal government of Iraq and the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region are still fraught as a result. Long-standing issues over territory and revenue-sharing remain unresolved.

The fundamental disagreement over foundational questions was also illustrated in the dysfunctionality of the 2005 constitution, currently under discussion with calls to visit it and redress the mistakes of the past.

Third, the formation of security architecture outside the official state apparatus has led to the rise of militias. These paramilitary groups did not only fill the security vacuum but also blurred the lines between security and governance. The governance sphere became highly driven by the security agenda instead of engaging with processes of democratisation and inclusivity.

Finally, the adopted approach to elections did not render the ballot box as an avenue for positive change. Within the existing framework, and as illustrated on a number of occasions, elections did not really disrupt political patronage, hence why the factional ethno-sectarian distribution of power remains mostly unchanged.

Elections in Iraq largely missed the crucial elements of representation, inclusivity, and accountability, and institutions providing checks and balances, all necessary for them to be perceived as meaningful. This has been manifested in the steady decline in voter turnout in recent elections.

'Uncertainty' as a constant

Two decades after the fall of the Baathist regime, processes of "reform, state-building and democratisation" continue to fall short in tackling the root causes of the Iraqi people’s grievances; meeting their demands; fulfilling their basic needs; and building representative and functioning institutions and a political system.

If anything, the ramifications of the invasion forced Iraqis to deal with a divided, fragmented society, with fault lines aggravated along sectarian identities, and politics, and the resultant violence.

It left Iraqis with a political system that enables corruption and absolves the political parties of accountability. It left Iraqis to confront the rise and demise of the so-called Islamic State. It left Iraqis to deal with complex processes of post-war reconstruction. But it also left them to struggle with consecutive governments and polity that failed to govern and deliver effectively.

Successive short-lived governments have developed plans and strategies to address Iraq’s problems but signally failed to fulfil their promises.

According to the results of the seventh wave of the Arab Barometer, as of today, Iraqi citizens perceive "corruption to be as high as their trust in political institutions is low".

Around 93 percent of Iraqi citizens believe that corruption is extensive in national state agencies and institutions, and just 19 percent of Iraqis report having trust in parliament, 26 percent in national government, 33 percent in local government, and 40 percent in the legal system (notably, 83 percent of Iraqis express a great deal or quite a lot of trust in the armed forces).

Additionally, with a plurality seeing parliamentary elections as "significantly flawed", Iraqis "bemoan the lack of governmental responsiveness to their grievances".

Only 20 percent say that government is very or largely responsive to citizens' needs, and 62 percent believe that their domestic system (including the current electoral system) should be replaced. Accordingly, per the survey, diverse Iraqis agree on two issues: that the only constant is "uncertainty", and that "reforming the system" is an immediate and not incremental demand.

Therefore, 20 years on, and as was argued in a recent publication by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute and the UN Development Programme, a critical entry point to change some of the above-mentioned dynamics requires a serious engagement in redesigning the social contract in Iraq.

At its core, a redesigned social contract in Iraq requires tackling corruption and delivering basic services, addressing security gaps, and ensuring gender and social equality to protect the most vulnerable and marginalised segments of the population.

This is not only vital to improve the daily lives of Iraqis, but also to meet citizens' expectations of the state and help the Iraqi people establish the homeland they seek.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.