Islamic State: Why leader's death is not a fatal blow

After the death of Islamic State (IS) leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi during a US raid in Idlib on Wednesday, questions have inevitably arisen over the group’s fate. The same happened after the death of former IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October 2019, but as I argued then, such questions are misdirected.

IS will survive, as it is an organisation structured in an amorphous manner, whose survival is not predicated on its leader, but on the chaos that gave birth to it. The socioeconomic and political conditions that initially led to the terrorist group’s formation will continue to enable its existence going forward.

Islamic State today is a far cry from the former self-declared caliphate that once straddled Iraq and Syria. And yet, it persists

The precursor of IS, al-Qaeda in Iraq, was founded in 2004 and led by Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who was killed in an air strike in June 2006. He was succeeded by Abu Ayyub al-Masri, an Egyptian bombmaker, who realised that an Iraqi should have a leadership role in Iraq’s insurgency and promoted Abu Umar al-Baghdadi, a former officer under Saddam Hussein.

Both were killed in 2010 in a joint raid between US and Iraqi forces near Tikrit, paving the way for Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi to become leader. His tenure of nine years at the helm, until his death in 2019, was relatively long.

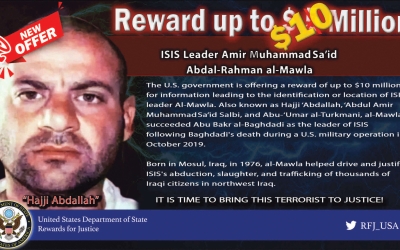

Qurayshi, who subsequently assumed the leadership, was also a Saddam-era officer. He hailed from the Turkmen community of the Iraqi town of Tal Afar, from where a number of former officers went on to serve in the higher echelons of the terrorist group.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Galvanised by incarceration

Exclusion, the denial of job prospects after 2003, and the neglect of Iraq’s rural periphery before and after Saddam’s rule are among the key factors behind Qurayshi’s rise to the IS leadership. Incarceration after 2003 also played a role.

Both Baghdadi and Qurayshi were imprisoned in Camp Bucca, a US facility where IS commanders came together as a nucleus. Once the prisoners were released, galvanised and hardened by their incarceration, they would revitalise the flagging group after 2010.

Another set of prisons near Baghdad were raided by IS in 2013, freeing close to 500 people who had been captured. This provided a pool of commanders and foot soldiers who were essential for the group’s offensive in Mosul a year later.

This raises questions as to what type of organisation might have formed in the Kurdish-guarded prison currently holding IS fighters in al-Hasakah, Syria, who escaped during a recent prison break. It remains to be seen as to whether the escapees will contribute to an IS resurgence.

After the collapse of the group’s self-declared state, Mosul reportedly became a refuge for its leaders and rank-and-file, who sought to melt back into the city. The anarchic border area between Iraq and Syria was another location, while IS remnants were also ensconced in the caves of Makhmour, southwest of Erbil.

Yet, IS leaders in 2019 and 2021 were found in Syria’s Idlib, held by Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, the al-Qaeda affiliate that once rivalled IS. This serves as a reminder that while the Syrian civil war has ebbed, it is not over - and IS continues to take advantage of it.

Symbolic blow

This examination of the past highlights policy measures that should be adopted on a micro and macro level by actors in the Middle East and abroad.

On a micro level, the symbiotic role of incarceration and IS needs to be addressed, particularly in light of the latest prison break. Western nations that have citizens in the Hasakah camps need to start repatriating them, especially children, who could otherwise become the future generation of IS.

Unfortunately, with attention focused on Russia and Ukraine, alongside the Biden administration’s pivot to Asia, Middle Eastern affairs are not being prioritised by the US or the international community.

On a macro level, the best strategy to ultimately defeat IS is not American raids, but a political solution to the Syrian war, alongside international reconstruction aid for Syria and Iraq.

IS today is a far cry from the former self-declared caliphate that once straddled Iraq and Syria. And yet, it persists. IS emerged with the collapse of the Syrian state after 2011 and the decrease in governing capacity in Iraq after the 2003 US invasion - problems that continue to this day. The death of Qurayshi has dealt a symbolic blow to IS, but it is by no means defeated.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.