Israel's vineyards want to be part of global boom in colonial wine

One of the most remarkable things about the newly emergent global wine culture since the 1990s is that it is not limited to Europe’s wine-producing countries.

Aside from France, and less so Italy, which had dominated previously, the newly marketed wine producers hail from European settler-colonies: Australia, New Zealand, California, South Africa, Argentina and Chile. Their wines have become widely available internationally since then.

The settler-colony of Israel has been trying hard to penetrate this market - albeit unsuccessfully, due to the non-competitive quality of its wines, except perhaps in limited venues in a few US and European cities and parts of the UAE. Recent surveys of global regions evaluating wine production around the world do not even mention Israel as a worthy candidate.

Acts of resistance increased when the colonists expanded their farming, at which point the peasants realised how much of their land had been stolen

Are the settler-colonial origins of these wines a mere coincidence, or has there been a settler-colonial history to wine production based on theft of native lands? An important episode in the history of European wine production was the devastation it experienced towards the end of the 19th century due to an infestation of the phylloxera insect, which feeds on grapevines. Phylloxera almost destroyed the French wine industry, with production falling between 1875 and 1889 by around 75 percent.

This was the era of high French settler-colonialism, especially in Algeria, which experienced new waves of settlers from the 1870s onwards. Most of the later settlers were impoverished farmers from the Midi area of southern France, who had escaped the poverty resulting from phylloxera’s destruction of the vineyards of Languedoc and Provence.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

With the provision of state and banking credit for white settlers, vineyards began to cover the Tell Atlas area of Algeria, where the profitable wine industry was established and prospered until Algeria’s independence. Dispossessed Algerian peasants did most of the farming work. Algerian anti-colonial resistance manifested in periodic attacks on the settler agricultural colonies.

As the Algerian example illustrates, colonial legal measures that privatise conquered lands are always instrumental for the expansion of settler-colonisation. In neighbouring Tunisia, another French settler-colony, the French between 1892 and 1914 usurped upwards of a quarter million hectares.

Colonial-settler agriculture specialised in olives and grapes to produce oil and wine. With official state-sponsored colonisation, the French displaced Tunisian peasants off land they had traditionally worked, but to which they did not possess title. This was also the fate of grazing lands lost to the colonists. Displaced and impoverished Tunisians attacked colonial farms.

Agricultural colonisation

In Palestine, the Ottomans in 1858 issued a Land Code that privatised land, which began to be acquired by merchants from inside and outside Palestine. Absentee landlords bought huge tracts and sold some to local agents of France-based Jewish philanthropic organisations, which were in turn financing agricultural colonies.

Meanwhile, the French vineyards of Baron Edmond de Rothschild, a major French wine producer, were devastated by phylloxera. He began to fund Russian-Jewish colonists to grow vines, and financed in 1883 the colonies of Petah Tikva and Rishon LeZion, where he wanted to establish vineyards and a winery.

The Russian colonial settlers established Rothschild’s first winery in Rishon LeZion on the lost lands of the village of Uyun Qarah in 1882, and another one soon afterwards in the colony of Zikhron Yaakov, built on the lands of the Palestinian village of Zammarin. Rothschild “followed the model of French agricultural colonization in Algeria and Tunisia”, dispatching agricultural and horticultural experts trained in French Algeria and France.

Palestinian peasants, like Tunisian and Algerian peasants, were evicted off lands where they had lived and worked for centuries. The first major peasant act of resistance against the Jewish settler-colonies occurred in 1886, when peasants attacked the Rothschild-financed Jewish colony of Petah Tikva. Peasant land had been sold to the colony after it was forfeited to Jaffa-based money lenders and authorities due to peasant indebtedness.

Yet, large parts of the land sold to the colony had not been forfeited, and in fact belonged to the villagers. Acts of resistance increased when the colonists expanded their farming, at which point the peasants realised how much of their land had been stolen. In the late 19th century, resistance was such that there was hardly a Jewish colony “which did not come into conflict at some time with” Palestinians.

Settlement wines

Close to a century later, in 1967, Israel invaded and occupied the Syrian Golan Heights and expelled 100,000 Syrians. Contravening international law, Jewish colonists arrived in droves, and Israel formally annexed the territory in 1981. Today, there are around 22,000 Jewish settlers living in 33 colonies in the Golan Heights.

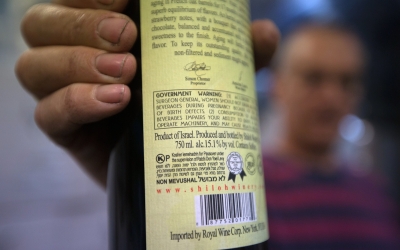

Some of the Golan colonies planted vineyards and began production of wine. In 1984, the Golan Heights Winery released its first vintage. Other wine producers include Jewish colonial settlements built on confiscated land in occupied East Jerusalem and the West Bank, such as the colony of Rechalim in the northern West Bank. This has created problems for Israeli wine exporters and embarrassed European importers.

The EU, Israel’s largest trade partner, decided in 2015 to label wines from Jewish colonies in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem and Golan Heights as products from “Israeli settlements”. This was ratified in 2019 by a ruling of the European Court of Justice.

The ruling resulted from a lawsuit brought by the Psagot Winery, a company based in the Jewish colonial settlement of Pisgat Ze'ev in occupied East Jerusalem, to reverse such labelling. Psagot’s vineyards are located on land in the occupied West Bank. But its lawsuit backfired; the EU court decision followed another 2019 decision by the Federal Court of Canada refusing to allow wine from Jewish colonies to be labelled “Made in Israel”.

An advisory opinion from a senior official of the EU court earlier likened Israeli wine from the colonial settlements to goods from South Africa under apartheid.

A different brand of apartheid

More than three centuries ago, Dutch and French Huguenot colonial settlers started South Africa’s wine industry on conquered native land. Much of the agricultural labour on South Africa’s vineyards was provided by the "coloured" population, who were paid with wine via the “dop system”, a form of unofficial enslaved labour that led to massive alcoholism.

After apartheid ended in the 1990s, coinciding with the neoliberal economic age, the still white-settler-owned South African wines began to be marketed internationally. Though illegal, the dop system continues in South Africa to this day, with estimates of its use in 2015 ranging between two and 20 percent of labour payments in the Western Cape.

Insistent that unlike South African apartheid, its brand of apartheid is more than acceptable to the Arab - and especially Gulf - regimes with which it recently established relations, Israel’s goal is to create a commercial niche for its substandard wines made on stolen Palestinian and Syrian lands.

Whereas the UAE recognises the Golan Heights as occupied Syrian territory and East Jerusalem and the West Bank as occupied Palestinian territories, Israel’s marketing its wines in the UAE as "made in Israel" would help push the recent legitimation its annexation of the first two received from the Trump administration in the last few years.

It remains unclear, however, if the UAE government or its courts will insist on labels that clarify that the wines are made in illegal Israeli settlements, or give the go-ahead for the "made in Israel" label.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.