'Til Kingdom Come: How Christian evangelicals fuel chaos in Palestine

In the Evangelical Christmas Lutheran Church in Bethlehem, Reverend Munther Isaac sits on a bench alongside Pastor Boyd Bingham IV, a Christian Evangelical pastor from a small American town, to discuss Christian Evangelicals and their role in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

"Evangelicals have contributed very negatively to this conflict because they are obsessed with prophecy," Isaac, a Palestinian Christian, tells Bingham, a hardline Christian Zionist from the Binghamtown Baptist Church in Middlesboro, Kentucky.

"See, what I don't get about many American evangelicals: in their scenario, Jews will either be converted to Christianity one day, those who won't sadly will be massacred - that is the prophetic understanding. Somehow, this is perceived as a theology that supports the Jewish people.

"To me, that is a twisted logic: the idea that God is bringing the Jews back to their land. But what is often missing is the Palestinian presence; it is as if you speak of an empty land. We have been at the receiving end of a theology that actually told us we don't belong here, that even told us we are second-class citizens in our homeland," Isaac adds, as Bingham looks on.

Their conversation is one of a series of remarkably incisive scenes in'Til Kingdom Come, a new documentary about the poorly understood and often underplayed bond between the Israeli right-wing and American Christian evangelicals.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

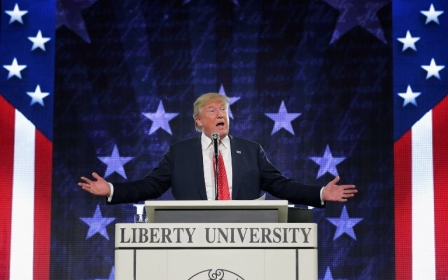

Directed by Maya Zinshtein, an Emmy-award-winning Israeli filmmaker, the documentary is an eyewitness journey into the fanatical world of the Christian Zionist movement in the United States as it unfolded feverishly during the Donald Trump presidency.

Christian Zionist base

Christian evangelicals comprise a quarter of the American electorate, and around three-quarters of the overall evangelical population are white. Many are Christian Zionists, who literally believe that Israel is a manifestation of biblical prophecies and that Jews must be supported to return to their spiritual homeland.

According to the movement's theology, once they are assembled in Israel, Jesus will return and bring about the mass conversion to Christianity for some Jews and death for the rest.

With the election of Trump in late 2016 and the very public and triumphant spirit that followed his Christian evangelical base into the White House, Zinshtein said it felt like an appropriate time to explore a story that few in Israel seemed to understand or care about, but which she envisioned would wield massive influence over the region.

The exposure to the inner machinations of this decades-old relationship makes the film a gripping affair

"When I started looking into this issue, I understood that there is huge power under the surface that influenced my life, the life of Palestinians who lived next to me... and I wanted to bring it to light," the filmmaker told Middle East Eye.

In the documentary, Zinshtein and her team explore the small evangelical community in Middlesboro, Kentucky, a microcosm of the larger Christian evangelical community in the US. She spends time with Bingham and showcases how both young and old are brainwashed into believing that supporting Israel would improve their lot in life.

'The destiny of this church'

Middlesboro is part of a belt of former coal towns that make up some of the poorest districts in the US. Despite 40 percent of its population living in poverty, the community is among the biggest contributors to the non-profit International Fellowship of Christians and Jews (IFCJ).

"The destiny of the Jewish people is the destiny of this church. And the destiny of this church is the destiny of the Jewish people," IFCJ president Yael Eckstein tells a packed church in Middlesboro, after receiving a cheque for $25,000.

"There is good versus evil. And God is saying: What side are you on?" she adds, to the roar of the faithful before her.

'Til Kingdom Come enjoys unfettered access to some of the most exclusive, intimate spaces in the US Christian evangelical world.

In Los Angeles, Zinshtein follows Eckstein into a fundraising event for the Israeli military, where Hollywood A-list celebrities such as Gerard Butler parade around figures such as the late Sheldon Adelson, the billionaire patron to Trump and supporter of Israel. Butler is later seen taking a selfie with Israeli soldiers while being flanked by Israeli TV hit series Fauda star Rona-Lee Shimon.

"It's a story of faith, money and political influence," Zinshtein said.

The exposure to the inner machinations of this decades-old relationship makes the film a gripping affair. Zinshtein is a masterful storyteller, allowing her characters to let their words and expressions tell the story, and even to challenge the main protagonists.

When Bingham tells Zinshtein on camera that "there is no such thing as a Palestinian," after a testy conversation at the church in Bethleham with Isaac, the audience is left with no doubt as to the bluster of the evangelical project.

Zinshtein interjects only to ask questions, but never to narrate.

Incomplete tale

Part of the intention of the film, Zinshtein said, was to illustrate to Israeli politicians on both sides that "when Israel signs on with the evangelicals, they sign on to their 'whole agenda'. And this agenda is anti-abortion rights, anti-LGBTQ rights, and these questions are very much in a different place compared to evangelicals." It is this burgeoning relationship between the Israeli government and the Christian right that concerns her.

After seeing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at a Christians United for Israel summit saying that American evangelicals were Israel's "best friends," Zinshtein recalled thinking: "This is insane. This scares me as an Israeli."

However, it is this framing that becomes the central weakness of the film. Nowhere do Zinshtein or her characters question Israel as a settler-colonial project that has systematically uprooted Palestinians, destroyed lives and occupied lands, even before the evangelical connection.

Despite the film's efforts to tell a complete story, the centring of Israeli concerns and fears that a hapless Israel has been saddled with a runaway, antisemitic behemoth is not just unfortunate; it is simply not the complete tale.

Though Christian evangelicals have a "plan" for Jews, their project remains theological, based on their interpretation of the Bible, and is largely a question of faith. While some Israelis might be uncomfortable that evangelicals have a massacre of Jews on their wish-list, it is also not something most Israelis take seriously.

For Palestinians, however, the fear is a lot more visceral and existential. At home, Israel has expelled hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, built a 700km wall through the occupied West Bank, and functioned as a US watchdog in the region. Abroad, Israel has long been allied with right-wing and racist governments, be it apartheid South Africa, Myanmar's military junta, or, most recently, the authoritarian and xenophobic regimes of Brazil and India.

Israel's partnership with the nativist, racist Christian evangelicals is, therefore, just one among a string of right-wing alliances. The film's failure to highlight the similarities between Israel and fanatic white evangelicals only serves to mainstream the notion that an alliance between Israel and Trump's abhorrent supporters is something of an anomaly.

But for Palestinians who have borne the brunt of this bond between fanatics for decades, and for those Jews who have attempted to highlight the settler-colonial ambitions of Israel, the bond represents the hollowness of Zionism itself.

"I really think that I am showing the key aspects of how this bond is influencing this question [the conflict]. The bottom line is that the Christian evangelicals believe that all the land that God promised Abraham belongs to the Jewish people. That means that anyone who gives [away] this land is basically a sin. And then we make these people our best friends, and so how exactly are we supposed to solve this conflict?" Zinshtein said. "My feeling is that the [question] of our [collective] destiny in this place is all over this film."

A question of history

Though it makes clear that Christian Zionism is not new, the film does not seek to clarify that the courtship between Christian Zionism and the Israeli right has been a long-term project, pursued by the Israeli state itself in the late 1970s and early 1980s under the leadership of former prime minister Menachem Begin.

"Begin's alliance-making was bolstered by the foreign ministry report that considered evangelicals a vital electoral force in American politics," Daniel Hummel writes in Covenant Brothers: Evangelicals, Jews, and US-Israeli Relations. "Under Begin, Christian Zionists became a key piece of Israel's diplomatic relationship with the United States."

It raises, and perhaps unwittingly so, an entirely different set of questions about the types of myths Israelis have held onto about their country for all these years

President Joe Biden's refusal to invalidate the US embassy move to Jerusalem, or his administration's dismissal of the International Criminal Court's decision to investigate Israel (and Palestinian groups) for war crimes and hesitancy to lift sanctions on ICC officials - all Trump-era decisions - show that Israel is still arguably the only policy matter that both Democrats and Republicans can reach a consensus on.

In Zinshtein's defence, the film could not have covered all of this. The narrative is led and shaped by her characters, and 'Til Kingdom Come explores one aspect of this relationship.

"I think that the film clearly shows that today's Israeli leadership - and you know we have had the same leadership for the last 10 years at least - they decided that the Christian evangelicals are our best friends. That's it. And they don't care what happens beyond that," Zinshtein said.

"Instead of saying we support the settlements, we support a right-wing agenda, they [Christian evangelicals] say we support the whole of Israel. And when you are an Israeli, you are not [going to] say no to support for Israel."

Erasing Palestinians

Still, the failure to probe how the Israeli state grapples with the so-called irony of working with Christian fanatics - or better still, to showcase how the state has used the tremendous clout of American Christian evangelicals to help inch its way towards achieving its own goals, such as settlement expansion, annexation and the erasure of the Palestinian people - allows the film to hint that Israel's destiny has been hijacked by fanatics.

'Til Kingdom Come, then, feels less like an indictment of the Israeli right. It raises, and perhaps unwittingly so, an entirely different set of questions about the types of myths Israelis have held onto about their country for all these years.

That it would take the grotesque bond with Trump to reveal the fundamental malfeasance of the Israeli state is perhaps the biggest irony of all.

'Til Kingdom Come is available to stream here.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.

![Yael Eckstein receives a $25,000 donation from the community in Middlesboro, Kentucky [Til Kingdom Come]](/sites/default/files/03_Yael%20and%20Boyd1.jpg)

![Pastor John Hagee from Christians United for Israel and Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu [Til Kingdom Come]](/sites/default/files/04_Bibi%20and%20Hagee0.jpg)