It is too soon to write the Muslim Brotherhood's obituary

Conditions for Islamist movements, parties and organisations across the Middle East and North Africa region have never seemed bleaker.

The brief political openings that followed the 2010-11 Arab uprisings saw some Sunni Islamist movements, such as Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and Tunisia’s Ennahda, capitalise on the removal of longstanding dictators and free elections to gain political power after years of being in opposition.

Yet, their successes were short-lived. The Egyptian Brotherhood was removed by a military coup in July 2013. Since then, the counterrevolution in Egypt has marked a global shift in which Islamist movements have been targeted with the goal of eradicating them. Islamists have been labelled as undemocratic political entities and even terrorist groups.

More than a decade after the uprisings, Islamist movements across the region are navigating renewed repression, political and social polarisation, and drastically altered circumstances. Yet, it is too soon to write the obituary of Islamism.

Islamist groups have historically proven to be extremely resilient and able to adapt to catastrophic circumstances, so the current bleak context could be an opportunity for renewal, rather than an indication of their imminent annihilation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Widespread backlash

As political scientist Marc Lynch notes, the “current catastrophe” of political Islam is characterised by some clear trends. Firstly, Islamist movements seized political space after the uprisings, but this opportunity was short-lived and often exposed their unpreparedness to rule, resulting in a widespread backlash.

Secondly, the return of authoritarian rule in the region has closed down meaningful opportunities for political participation, as the global campaign against Islamism waged by the UAE has restricted the ways in which Islamist movements can gain legitimacy and resources. Islamists are being widely demonised once again, significantly impeding their potential return to political life.

The dimension of exile creates space to engage in new forms of political organising, ideological revision and long-term strategic thinking

Thirdly, renewed repression and forced exile have dealt a heavy blow to Islamist movements’ organisational structures, historically a source of their strength. Assets have been seized and hierarchies shattered, leading to widespread defections and internal splintering over ideology, direction and strategies to respond to repression. As a result, Islamists’ historical commitment to non-violence and peaceful resistance has come into question.

Lastly, Islamist movements face deep ideological and strategic challenges, as their commitment to moderation and peaceful political participation, which allowed them to thrive for decades, has led to destruction and persecution. They must now stipulate a new set of strategies to rebuild their popular bases and appease younger cadres unsatisfied with the passive resistance embraced by senior leaders.

All the same, Islamist movements have proven to be resilient to difficult circumstances in the past, suggesting the same can happen now, although their direction remains uncertain.

Harsh crackdown

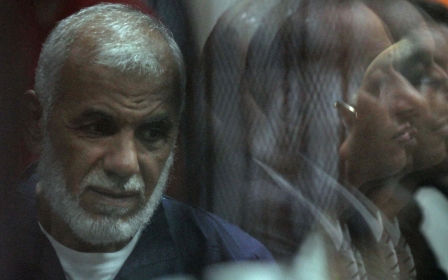

The Muslim Brotherhood, the oldest Islamist movement with which many contemporary Islamist groups and parties share a range of organisational and ideological traits, is facing one of the harshest crackdowns in its history since the 1950s. In Egypt, the group was able to capitalise on the brief period of political opening that followed the removal of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, securing electoral victories in parliament and the presidency.

But the movement failed spectacularly at governance, and since the 2013 coup, it remains under heavy repression. Thousands of key leaders and rank-and-file members and supporters have been arrested, killed or forced to live in exile.

Yet, the unprecedented circumstances that the Brotherhood faces, along with external and internal challenges, also hold significant chances for revival. The dimension of exile creates space to engage in new forms of political organising, ideological revision and long-term strategic thinking.

Since its establishment in 1928, the Brotherhood has faced repeated crackdowns by Egyptian regimes, which co-opted the group into the political system or repressed it. In all instances, the Brotherhood demonstrated the ability to resist repression and to re-emerge as a powerful sociopolitical force when favourable circumstances for participation materialised once again.

Indeed, the Brotherhood has learned to capitalise on repression, turning it into a source of strength and cohesion. Regime repression has thus helped the group to garner public support by strengthening its image as a legitimate opposition actor, reinforcing members’ commitment to its cause, and sparing it the need to revise core ideological traits or strategies, in favour of an approach promoting steadfastness in the face of adversity.

The Brotherhood is thus well-positioned to survive the current wave of repression by relying on tools of resistance, such as organisational strength and its ability to foster a strong collective identity among members.

Uncertain future

As we have argued elsewhere, however, there are four dimensions of the current crackdown that make it qualitatively different from the Brotherhood’s past experiences, thus casting uncertainty on how the movement may re-emerge from repression in the future.

Firstly, the brutality of the Sisi regime has been indiscriminate, marking unfamiliar territory for some members across the organisational and generational spectrums. Secondly, repression emerged just after the Brotherhood failed at its first experience in government, causing many members to question the group’s political vision and project.

Thirdly, repression has opened a significant space for younger members to act independently from the organisation and to advance their own initiatives, political agendas and ideas, challenging core principles such as blind trust and obedience to the leadership. And finally, the Brotherhood now faces the unprecedented task of having to reunite while in exile.

The dimension of exile has also favoured further internal fragmentation, with the most visible effect being the establishment of a second Guidance Bureau in 2015 by a small cohort of members over disagreements on how to respond to regime repression. This marked the first serious internal split since the 1950s.

Importantly, after 2013, the Brotherhood found itself fragmented not only along vertical lines, as its hierarchical structures were increasingly challenged, but also across geographical contexts due to the new dimension of exile. Members of the Turkish diaspora led the way for internal renewal through their engagement in new forms of activism and cross-generational, cross-ideological alliances, taking advantage of a sociopolitical context more favourable to their presence and activities.

Qualitative shift

The Brotherhood’s fragmentation, along with the unfamiliarity of exile and the opening up of opportunities for sub-groups such as women and youth to exercise greater agency, complicates the process of regrouping. It creates the necessary conditions for internal change, as members take stock and build on past experiences to reunite and rebuild the Brotherhood.

Indeed, young members, and those who briefly left the movement because they were disillusioned or expelled for activism that contradicted Brotherhood policies, are slowly circling back to the mother organisation. Yet, many continue to pursue alternative venues for activism and are engaged in the process of rethinking the Brotherhood’s core ideological principles and goals.

Islamist movements are not monolithic actors. More emphasis should be given to the roles of individual members

The trajectory that the Brotherhood has taken since 2013 shows that the movement is on a path of renewal, spurred by internal debates over key issues such as organisational structures, ideology, leadership and values, often led by actors who used to occupy a marginal position in the group. What remains to be seen are the lessons that the movement and its members will draw from their experiences since the uprising.

As the Brotherhood’s modus operandi is questioned and reshaped, the movement finds itself in a unique position. Observers should take note of the key contemporary forces shaping Islamist movements, in order to fully capture their current and future trajectories. This requires a qualitative shift in how we study and understand Islamist movements, moving away from binary categories such as “radical” and “moderate” that have long dominated analyses.

Islamist movements are not monolithic actors. More emphasis should be given to the roles of individual members, and how they are shaping questions pertaining to politics and ideology, along with how geographical contexts contribute to the emergence of ideological cross-fertilisation with other political actors, leading to new collaborations and alliances.

The roles of previously marginalised actors must also be fully captured, including those of women and youth. While there are some global signs that Islamism might be “running out of steam”, a closer examination shows that movements such as the Brotherhood are not dead - and there is a strong opportunity to foster resilience and internal revival.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.