Jamal Khashoggi's long shadow

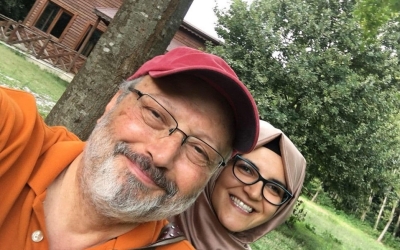

A year ago on Wednesday, Jamal Khashoggi stepped into the Saudi consulate in Istanbul to get a paper that would allow him to marry his fiancee Hatice Cengiz.

There was a spring in his step. The paper declaring his divorce was a formality. His closest Saudi friends had warned him the previous week not to step foot inside the consulate, but Jamal brushed them aside, relying instead on his inside knowledge of how Saudi embassies worked.

A year on from Khashoggi's murder, the Saudi crown prince finds himself in a very different place

His future in Turkey and Washington was ahead of him. After months of indecision, homesickness and loneliness, Jamal had made up his mind. He did not get back in touch with his friends when he returned to Istanbul from London. He went straight to the consulate.

Within seven minutes he was dead, the victim of a medieval act of butchery.

The death squad did not just answer the question of who would rid Mohammed bin Salman of a "troublesome priest" - words attributed to Henry II about the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Khashoggi's murder changed the course of Mohammed bin Salman's rule itself. A year on, the crown prince finds himself in a very different place.

In retreat on all fronts

The oil-for-security alliance with America is over. Two of Saudi Arabia's biggest oil terminals were attacked in what Mike Pompeo, the US secretary of state, called an "act of war" by Iran, and US President Donald Trump walked away - for entirely realistic and pragmatic reasons.

Bin Salman's brutal campaign in Yemen is in tatters. His main ally, the Emiratis, have deserted him. They are content to divide Yemen in two and leave the Houthis where they were in the north. A few weeks ago, the Houthis launched a mass attack in which they claimed to have captured 2,000 pro-alliance soldiers, including Saudis.

Far from bringing the battle to the heart of Iran, as he had promised to do, the Saudi crown prince has wrought havoc in the heart of his kingdom. Iran's President Hassan Rouhani revealed that he had received a letter from Saudi Arabia, through an intermediary - the Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi.

We do not know what the letter said, but one can surmise it was not a declaration of war.

A year on, the crown prince is in retreat on all fronts. Mohammed bin Salman still reigns at home with an iron hand. The continued prosecution of religious scholar Salman al-Odah, for charges that would lead to a death sentence, is testimony to that.

But his charm offensive in the West is over. Bin Salman is no longer courted as an extremely rich moderniser, the young prince in a hurry, the reformer who cuts corners, lauded by columnists such as the New York Times' Thomas Friedman.

His name is toxic to US brands. Consultancies are deserting, not queueing up to join. No one is talking anymore about flying taxis, robots and cities rising in the desert.

For much of this, Khashoggi is personally responsible. He, by the way, initially supported Mohammed bin Salman's reforms. He recognised that Saudi Arabia had to change radically. What he criticised was how those reforms were being done.

The opposite effect

Unhappily for his butchers and for the crown prince whose personal bodyguards supervised the operation, Khashoggi's murder and dismemberment turned out to be one of the most recorded in history.

Saudi Arabia tried everything it could to efface that record. They invited the head of Turkish intelligence to Riyadh, claiming the whole affair could be dealt with "in an afternoon". The offer was declined. They offered to bribe Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. He refused. They destroyed the forensic evidence. That was to no avail. The CIA added their own records of telephone intercepts, concluding that Mohammed bin Salman ordered the assassination of Khashoggi.

The Saudi crown prince ordered this assassination because he wanted to silence all whistleblowers. Khashoggi had been part of the establishment and the crown prince, an admirer of Russian President Vladimir Putin's attempts to poison Russian dissidents in England, wanted to make the same point: no Saudi was beyond his reach.

Besides, Khashoggi was Saudi property. Khashoggi was bin Salman's goods and chattel. He, the crown prince and future ruler, could do what he wanted with his subjects. That is what being an absolute ruler meant.

Khashoggi's murder had the exact opposite effect. From that October day on, Mohammed bin Salman would never be able to crawl out from under Khashoggi's shadow. When the CIA's director, Gina Haspel, and Washington DC turned definitively against him, the crown prince went into crisis mode. He has been there ever since.

He set up an emergency committee whose task was to deal with the fallout from the murder. They came up with a series of bizarre ideas, one of which was for a "game-changing" Camp David style summit between the crown prince and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

That came to nothing. He tried courting China as a counterweight to the US. That did not help either. Every time Mohammed bin Salman thought he had banished Khashoggi's ghost, it has come back to haunt him.

Nothing inside the kingdom has changed. Dissidents and business rivals are suffering horrendous conditions in Saudi prisons. The repression is as harsh as it ever was. Mohammed bin Salman himself has learned nothing from his serial policy failures.

New lease of life

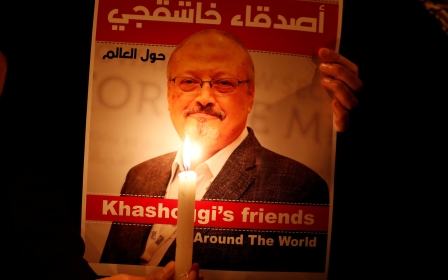

But Khashoggi's murder has given the role of the Saudi dissident - one that he never wanted for himself - a new lease of life. The impact of his death, which continues to this day, has given new hope to the Arab world in a way that goes far beyond one crime, one of many, which will go unpunished.

Khashoggi's message to the Arab world is one of hope. If his life and work boiled down to one message as a Saudi journalist, it was this: the status quo in Saudi Arabia cannot continue. It is doomed to collapse. He was right. The mood of pessimism which settled on the Arab world after the crushing of the Arab Spring in Egypt in July 2013 has lifted.

Egypt's President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi literally had to lock down his major cities to prevent Egyptians taking to the streets at the weekend calling for his removal. Six years on, protesters have found a new voice and can affect political change. In Sudan and Algeria they already have.

Tide of history

The tide of history is once again turning, and its absolute rulers and military dictators are on the wrong side of it. Khashoggi was not a revolutionary. He was an establishment figure. He was also a modest man. I do not think he would have remotely imagined his death would have had the effect it has had.

Khashoggi will not fade away with time. If anything, the image of the man who campaigned for a modicum of freedom of speech in his country will grow with time. Khashoggi's final story - that of the slain journalist - has had a journalistic power unrivalled by any of his columns.

In sealing Khashoggi's fate, Mohammed bin Salman sealed his own.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.