On Jean-Paul Sartre and Palestine

In June 1967, five years after independence, Algerian students set fire to the books of Jean-Paul Sartre - Sartre, who had been a great friend of the Algerian revolution.

Around the same time, Josie Fanon, widow of the psychiatrist and anti-colonialist essayist Frantz Fanon, asked his publisher to remove Sartre’s forward to The Wretched of the Earth. “From now on, there is absolutely nothing in common between Sartre and us,” she declared.

A ban of Sartre’s books was announced in Iraq, and Arab intellectuals across the board began disavowing their kinship with the philosopher from the Paris Left Bank.

By coming out in favour of Israel on the eve of the 1967 Six-Day War, Sartre essentially put an end to the Arab existentialist movement, discrediting in one fell swoop his revolutionary stance on the struggles for freedom across the Middle East and North Africa.

Sartre and the creation of Israel

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In 1947-48, Sartre and the majority of French intellectuals on both the left and the right of the political spectrum were in favour of the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine.

“I have always hoped, and I continue to hope, that the Jewish problem will find a lasting solution within a humanist framework free of borders. But since societal transformation inevitably involves a period of national independence, we can only welcome the fact that an autonomous Israeli state has given legitimacy to the hopes and struggles of Jews throughout the world,” he is quoted as saying.

Torn between his political convictions and his 'emotional determination', Sartre chose the middle ground - an ambivalent stance he maintained in a convoluted and often contradictory manner

His words marked a radical break with his earlier stance on the Jewish question. In an essay entitled “Antisemite and Jew”, he wrote: “It is the antisemite who creates the Jew ... who compels the Jew to make himself a Jew in spite of himself.”

His words also stood in stark contradiction to his political engagements with struggles for liberation in Cuba and Vietnam, and against the “cancer” of South African apartheid and the segregationist regime of the US, a stance no doubt shaped by two factors in particular: the recent end of World War II and the horrific reality of the Nazi concentration camps, which, according to Sartre, had forged the “emotional determination” of French intellectuals on the question of Palestine and the wider Arab-Israeli conflict.

“Thus are we allergic to whatever may resemble, in one way or another, antisemitism. Many Arabs will reply: ‘We are not antisemitic but anti-Israeli.’ And they are no doubt correct: but they cannot keep us from thinking that those Israelis are also Jews,” Sartre wrote in 1967 in Modern Times, a journal he co-founded with Simone de Beauvoir.

Then there was the political context of the period, the de-colonialist enthusiasm of Western intellectuals unthinkingly granted to the creation of a Jewish state - ignoring the existence of the native Palestinian population.

Right to self-determination

Throughout the 1950s, Sartre was silent on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At the same time, he redoubled his efforts in favour of Algerian independence: He published numerous pro-revolution articles and the essay “Colonialism is a System”, a powerful piece deconstructing colonialism as a system of exacerbated violence.

During this period, he was the darling of the Arab intelligentsia, won over by his outspoken views and the image he had honed of being a committed intellectual. From Algiers and Baghdad to Cairo, Damascus and Beirut, he was one of the most widely translated, debated and celebrated intellectuals.

For Sartre, the question of Palestine could no longer be avoided after the independence of Algeria in 1962. Torn between his political convictions and his “emotional determination”, Sartre chose the middle ground - an ambivalent stance he maintained in a convoluted and often contradictory manner.

On the one hand, he consistently condemned the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and championed the right of return; on the other, he supported the existence of Israel as a sovereign state. These efforts to remain “neutral” entailed an intellectual crisis.

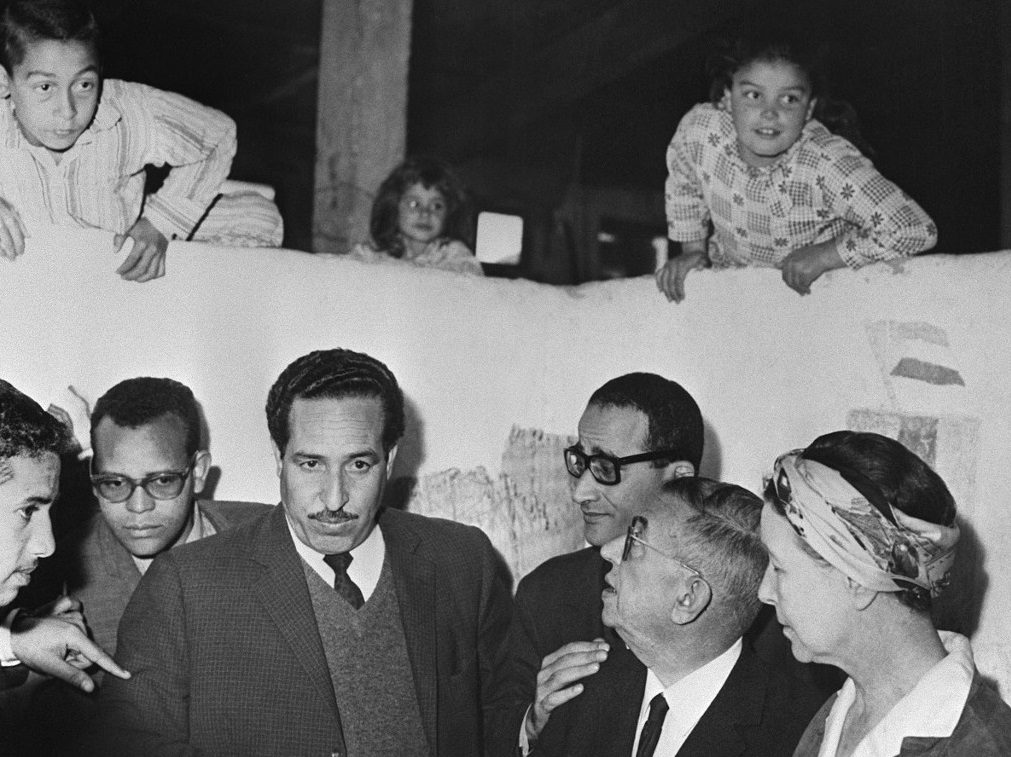

In February 1967, Sartre visited Egypt, Gaza and Israel to investigate the conflict, speaking with students, activists, refugees, women, workers and party members, including Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. In his book No Exit, historian Yoav Di-Capua describes the intricacies of organising such a visit - not to mention the heavy political consequences, with both sides of the conflict vying for the celebrated French philosopher’s support. Everything he said was picked apart, analysed and interpreted as a possible sign of support.

Meanwhile, more and more editorials and statements urging Sartre to take a firm stand were being published by Arab intellectuals, who saw his neutrality as a sign of support for Israel.

A spectacular reversal

Shortly after his celebrated visit, tensions between Egypt and Israel led to a military escalation in the region that garnered considerable support in France in favour of Israel which, amid associations of former combatants and returnees from French Algeria, turned into a racist, anti-Arab campaign.

In this context, a petition in support of Israel was published in Le Monde. Sartre was among the signatories, proclaiming in black and white the French philosopher’s breakup with his Arab friends. Only later would they learn that Sartre had been loath to sign.

From the 1970s onwards, with the intensification and export of the Palestinian struggle in Europe, the opinions of left-wing intellectuals on Israel underwent a spectacular reversal. Sartre would even go so far as to support suicide attacks.

“I have always supported counterterror against established terror. And I have always defined established terror as occupation, land seizure, arbitrary arrest, and so on,” he noted.

Israel was no longer seen as an island surrounded by hostile Arab waters, but as a cog in the US imperial machine - and an over-militarised cog, to boot, attacking a people crushed by centuries of Ottoman, and later British, occupation.

In June 1972, Sartre addressed a letter to the mother of an Israeli conscientious objector, in which he affirmed that “it would be to the court’s credit to acquit [the accused] who is facing years in prison for a courageous and concrete act: to refuse to serve in what was initially an army of preservation, but which has since deployed offensive tactics and become an occupying force”.

Struggle for freedom

So how did this political reversal come about? The answer can perhaps be found in an interview Sartre gave to the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram, and which appeared in the Lebanese existentialist magazine Al-Adab, in the months following the publication of the controversial petition.

Sartre, who had retreated into silence after the controversy, said his signature was only a stand “against the looming [Six-Day] war” and not against the Arab and Palestinian people’s “struggle for freedom and progress”.

He condemned Israel’s use of napalm, which he described as a “criminal act”; he recalled why French public opinion had been favourable to Israel in the 1967 war, claiming that the French stance had been fuelled by fears of witnessing a second “attempt to exterminate the Jews” and by ignorance about what was really going on.

He also declared that “wars of liberation are the only legitimate wars”, condemning Israel’s expansionist intentions and describing the plan to annex Jerusalem as “absolute madness”. Lastly, he said he regretted the “powerful reactionary forces” gaining ground in Israel and preventing all possibility of peace.

In 1976, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In his acceptance speech, he said he would have likewise been honoured to receive such a title from the University of Cairo.

In 1979, he organised a seminar for the advancement of peace in the Middle East. Both Israeli and Palestinian intellectuals were invited. He died a year later, on 15 April 1980.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article was translated and condensed from the original version in the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.