Let Syria have its voice

In the summer of 2013, I had a meeting with three international staff working for different organisations concerned with Syria. Two of them talked about conducting a study in southern Syria, and since I am originally from Daraa I was interested in offering help and contacts.

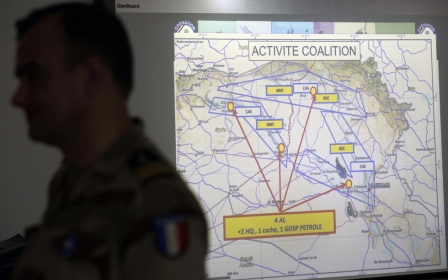

The third expat silenced me, telling me I was wrong and that there was no place in Syria called Daraa. Pointing at the map, this person spent 10 minutes telling me what my hometown was correctly called, and mentioning the names of towns and villages unknown in Syria.

I was bewildered by the over-confidence of someone who was working on Syria for a big European organisation and who had never been to Syria before, but who was not ashamed to claim a superior knowledge and to vigorously hush me up.

It was clear to me and the two other international staff that the places being reeled off by the expat were in southern Turkey, not southern Syria. I wanted to turn the map round and give an elementary lesson in geography, but I swallowed my anger.

That was one of countless incidents in the Syrian context where power is not defined by knowledge or experience but often by the hegemonic over-confidence of many Western pundits and aid professionals.

This article does not set out to claim that only Syrians have the right to speak, write, or work on Syria, or to make blanket generalisations about outsiders.

There are indeed some analysts and expats who have great knowledge of Syria, have genuine passion for and interest in the country, and understand the context and its sensitivities. Presumably, these are the ones who speak only when they can contribute to the debate rather than just adding their voice to the chorus or chasing after media exposure.

Syrian voices have been silenced both voluntarily and by force. This silence is deeply rooted in the generations of dictatorship, oppression and fear we grew up with. Latterly it has been the result of the shock, anger, exhaustion and frustration that have built up over the past five years.

In many cases – and I include myself here – we silenced ourselves because of a lasting feeling of paralysis and helplessness because the Syrian catastrophe has become indescribable, because our voices have never been really heard, and simply because speaking or writing about Syria exhausts us.

It brings back the trauma of losing our homeland and loved ones and reminds us of the individual and collective memories of a country that formed us as human beings.

This form of silence can be comprehensible. However, the question is whether we have been given the space in geopolitical debates that we deserve or has it been filled with the voices of Western pundits eager to teach us about our own country?

In political debates and the media, we are often perceived as emotional and unbalanced. While this might be true to some extent, I wonder why we shouldn’t be. For the majority of Syrians, Syria is not an opportunity, not a career, and not a mere narrative.

For us, Syria is years of subjugation, agony and fear that are unfathomable to most of the pundits who claim to analyse Syria.

They can be more "balanced," "rational," and "emotionally detached" because they do not have to worry about their families suffering every minute of their lives; while sitting in Washington, London or other capitals, they have not experienced what war means. Hence they are able to talk and write incessantly about Syria and simplify what is happening down to a simple "civil war" or "Islamic State".

Many Western pundits and expats, even those who have never been to Syria, have indeed learnt about the country after five years of war there and have built their careers and reputation in the academic, geopolitical, humanitarian or development spheres. In many cases, they require or use Syrians to "milk our brains" or to do fieldwork inside the country for which they take the credit.

Some of them will start every speech they make or article they write with a reference to the one and only day they managed to cross into Syria. They never forget to picture themselves with a Syrian child. They dip in and out as tourists and then market themselves as heroes.

When some Syrians manage to go back to the country, whether to the regime- or opposition-held areas, we risk our lives and we conceal our visits even from ourselves. For security and ethical reasons, it takes a long time before we are able to process and reflect on our homeland and our exile.

In the humanitarian and development business, many expats have been funnelled into the country through UN agencies and international organisations.

Here they have the advantages of power and money, and they gain pseudo-knowledge and a sense of superiority. The expats ask Syrians to implement the work in conflict and besieged areas, transfer the risk to "locals" while paying them very little, and then present themselves as swashbuckling pioneers.

How has this happened? In her book Knowledge in Context: Representation, Community and Culture, Sandra Jovchelovitch, professor of social psychology at the London School of Economics, explains that the European mind, even after the end of the colonial era, still sees itself as the supreme achievement of history.

She writes: "As long as the modern ego does not recognise its own destructive tendencies, it will continue to imagine its own as the most developed and most superior civilisation, and in accordance with this sense of superiority will feel obliged to educate, to civilise and to develop lesser civilisations."

So there is a "hierarchy" of knowledge; knowledge does not depend on understanding and relevant context, but rather on the language and status of the speaker.

This is what enables some Western pundits, academics and expats to act like bulldozers and believe they can be more Syrian than the Syrians themselves.

The Syrian people may feature in poignant stories of suffering, but these are often seen merely as good journalism rather than as an indispensable part of the political debate in which the actors should be engaged. It is time to recognise our voices and respect our agency in determining the future of our country; we are simply tired of being the animals in the zoo.

-Kholoud Mansour is a former Academy Senior Fellow at Chatham House and Senior Consultant at the Local to Global Protection Initiative. This article was first published in The World Today.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Syrian woman mourns on the grave of her son of the first day of Eid al-Adha holiday in the rebel-held southern city of Daraa (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.