'Diary of a siege': The secret of Palestinian resilience revealed in film

What is the secret of Palestinian resilience and steadfastness, or what they call sumud? Decade after decade, they have faced brutality, dispossession and barefaced thuggery at the hands of those who face no accountability, yet still have the audacity to play the victim. Imagine yourself a Palestinian: how do you do it?

Allow me to share a story. Quarantined and tucked away at home these days, I watch most everything on my little iPad screen, positioned inches from my face and using headphones to keep the noise and occasional inappropriate words away from my younger children.

The fact of Palestinians living under siege, occupation, dispossession, exile and destitution begins to morph into something allegorical

This is not an ideal way to watch films, especially for my generation, which was born and raised on big screens. But the Covid-19 pandemic, combined with advances in digital technologies, has made this mixed blessing possible. Pandemic isolation now comes with Netflix, HBO Go, Amazon Prime, Hulu and God only knows what other streaming channels. But God forbid if you are at the mercy of these corporate tastes and their nonexistent corporate wisdom.

Over the Christmas break, I was treated to a personal Palestinian film festival, courtesy of one of the greatest living Palestinian filmmakers, Nizar Hassan. From his home near Nazareth, he curated a bold and revelatory collection of recent works for me. We communicated over WhatsApp, email and text messages, and adjusting for the time difference between New York and Nazareth, we held post-screening discussions over tea and coffee, despite being half a world apart.

We talked politics, life, good films and terrible films, as we exchanged the latest on our personal lives, families, previous projects and upcoming projects. Then, we adjourned until the next film. It was like being in the Cairo, Cannes, Berlin or New York film festivals - except this one was online and entirely devoted to the most recent Palestinian films.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Life under siege

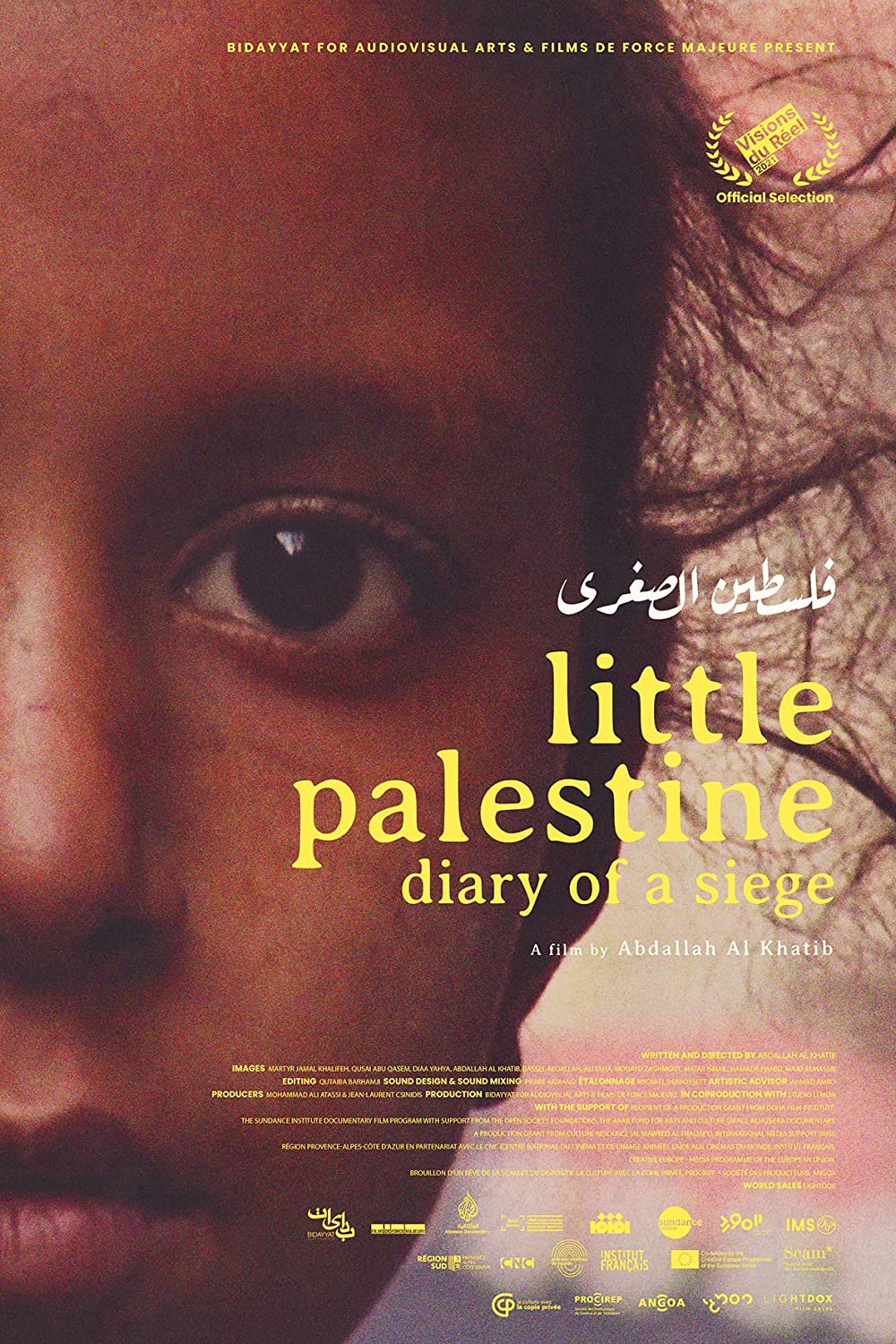

A major film I saw in this way was Abdallah al-Khatib’s Little Palestine (Diary of a Siege), about Yarmouk refugee camp in Syria, home to thousands of Palestinians, which emerged as a major battlefield during the Syrian revolution and subsequent mayhem. The documentary follows the lives of ordinary Palestinians under siege, with careful attention to detail, an insider’s touch and vivid clarity.

Throughout the film, Khatib’s camera becomes an inconspicuous resident of the camp - always there, invisible to itself and to others. It is impossible to imagine any other filmmaker, except a lifetime resident of the camp, being able to place and move a camera so imperceptibly, while capturing integral images of a landscape we learn to embrace.

There does not appear to be much online about the film or the filmmaker, but a description on the Rotten Tomatoes movie review site notes: “Between 2011 and 2015, he [Khatib] and his friends documented the daily life of the besieged inhabitants, who decided to face bombing, displacement and hunger with rallying, study, music, love and joy. Hundreds of lives were irredeemably transformed by war and siege - from Abdallah’s mother, who turned into a nurse taking care of the elderly at the camp, to the fiercest activists whose passion for Palestine got gradually undermined by hunger.”

I began reading more on Khatib, who reportedly studied sociology at the University of Damascus and was active prior to the Syrian uprising with the UN refugee agency in Yarmouk. Now, the poetic disposition of the film became more meaningful.

Khatib’s poetry, titled 40 Rules of Siege, hovers over the documentary like a wandering ghost: “When the future sticks out its tongue sarcastically/When the most obvious answers to simple questions/Are as rare as a lump of sugar.” Here, we realise that what Khatib has brought before his camera is a fusion of evident facts and liberating visions, otherwise hidden to casual observers of Palestinian lives.

Suffering and joy

This is when the dystopia that we witness with our own eyes begins to promise a utopia that never was. The fact of Palestinians living under siege, occupation, dispossession, exile and destitution begins to morph into something allegorical. Human suffering morphs into joy, pain into laughter, despair into happiness, abandonment into living care.

Khatib does not blink at the suffering he shows us, nor does he imagine things that are not there. It is all there, but it requires a poet’s eyes to convey the true meaning.

Here, we come back to the question: how do Palestinians survive? What is the secret of their resilience, and what can the world learn from that resilience? The space between this and similar films on the one hand, and the circumstances under which Hassan arranged for me to see them on the other, now come together. We are not in control of the calamities that befall us, from a global pandemic to European colonialism. But we are in control of how to turn those facts around, to have them signify a world we must purposefully reclaim.

The circumstances under which Khatib connects to the outside world are themselves revelatory. According to a 2015 Guardian article, “during a Skype interview from his home, Khatib disconnects every half an hour. He has five laptops that he charges every night on a generator because electricity is cut off. The laptops belonged to activist friends who were killed, one on the first day ISIS [the Islamic State] arrived as he tried to document the invasion with his camera.”

The same situation persists in all other Palestinian refugee camps in and out of Palestine, perhaps in Gaza most particularly. But life must go on, and it does. Consider rule number one from Khatib’s 40 Rules of Siege: “There is a direct relationship between love and death/The more you love love, the more you fear death/And the more you love death, the more you fear love/Me, I am afraid of love.”

'Thread of sunlight'

The born poet is condemned to see beauty in everything. As the Guardian piece noted: “Abdullah al-Khatib pondered the sniper bullet that had pierced the window of his home close to the besieged Yarmouk refugee camp. Astonishingly, he was grateful. ‘The sniper had wanted to kill someone, but that hole has allowed a thread of sunlight to pierce through,’ he said. ‘Everything has two sides. There is nothing that lacks beauty.’”

But what exactly is the documentary about? One reviewer begins with the right note: “Quite why the refugee camp … should be a target for siege, other than the ubiquitous excuse that it is being infiltrated by Daesh (ISIS) rebels, is never explained. But then this is not a documentary about the Syrian war, but a portrait of some 160,000 poor people crammed into a couple of square kilometers of crumbling, war-torn concrete apartment blocks, trying to survive after a lifetime of trying [to] survive against the odds.”

In that transmutation of digitised relics into uncompromising truths dwells the endurance of the Palestinian cause: their sumud

One should not romanticise Palestinian suffering or sugarcoat it with poetry. Palestinian poetry, from Mahmoud Darwish to Khatib, is not pretty; it is not beautiful; it is real. We stand in awe of that reality.

What has been done to Palestinians is barbaric, and those who have done it - and who live triumphantly on their ruins - are barbaric. The poetry of Khatib or Darwish does not sugarcoat that barbarism. Instead, it yields to a sense of sublimity coterminous with the reality it sees and the truth it speaks.

It takes a bold and daring poet and artist in Syria, a master documentary filmmaker in Palestine, and a witness quarantined at home halfway around the globe to turn the digitised fragments of their lives around to see something beyond these limitations, reaching for an allegory of our earthly whereabouts. In that transmutation of digitised relics into uncompromising truths dwells the endurance of the Palestinian cause: their sumud.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.