Local government could change things for Tunisia's disillusioned young

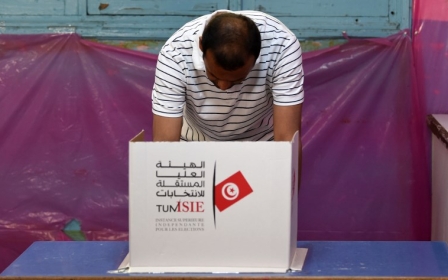

Last week I sat with a group of young political activists in Mornaguia, a mixed middle and working class suburb of Tunis, the Tunisian capital. They were newly elected local councillors, under 35 years old, who'd won seats in the 6 May local elections, the first local elections since the 2011 revolution.

As I listened to their plans and aspirations, I could sense how empowered and energised they were to address challenges in their own communities. They identified significant issues that are common across the country: fixing pot holes in the roads, cleaning up their neighbourhoods and reforming the management and administration of local authorities, among many others.

A frustrating experience

After the massive uprisings in 2010-11 that brought young Tunisians to the streets and ignited protests across the region, the past seven years have been a deeply frustrating experience for the country's younger generations. They hoped for a freer, richer and more socially just society, but their expectations were dashed as leaders struggled to deliver change and reverse decades-old patterns quick enough.

One in every third person under 35 years old is unemployed in Tunisia, twice the national average. Soaring inflation, a depreciating currency and external shocks like rising oil prices sucking away government revenues have only added to their sense that change is needed more than ever.

Young activists across the country have won popular mandates at the ballot box. They have gained recognition, not as a result of protest, demonstration, or obstruction, but through campaigning and winning a mandate from their own communities

The effects of such conditions reach across the country. Under-35s represent 60 percent of the population and too little has changed for too many young people who have little prospect of getting work that will allow them to get on in life, establish their independence or start their own families.

But for the first time since 2011, the local elections may change the tide. Young activists across the country have won popular mandates at the ballot box. They have gained recognition, not as a result of protest, demonstration, or obstruction, but through campaigning and winning a mandate from their own communities to bring the change for which they have longed.

For all its challenges, Tunisia's civil society has flourished during the transition. Young people have managed to engage politically, working for accountability and transparency, human rights and transitional justice. But for many, this was never enough. They wanted to be a part of the decision-making process.

Their inability to find the space to do so led to a high level of disillusionment and frustration with the Tunisian political establishment. This was reflected in their political participation: although exact data has not been released, turnout among young people in recent elections is widely acknowledged to have been low.

The rejectionists

In 2012, at a meeting held in Tunisia with political leaders from a variety of parties, politicians were concerned about young activists who not only did not participate in - but also actively rejected - the political transition. These activists feared that their revolution had been stolen by an older generation. They had come to call themselves 'rejectionists'.

Several politicians asked us to facilitate a dialogue between the activists and the leaders – members of parties, ministers and members of parliament – to open a space for engagement on the issues under debate at the time.

At the beginning, as is often the case, such meetings were tense, with a sense that little deference was being paid between participants. Over time, more young leaders from across the political spectrum - including political parties and civil society - participated in the meetings, eager to be involved and share their perspectives.

With national politics hard to break into, young people recognised that local politics could be a space in which to cut their teeth and gain valuable experience. And after repeated delays, the first local elections since the revolution were held. Across the country, independent candidates came first in the elections (32 percent), ahead of Ennahda (28.6 percent) and Nidaa Tounes (20.8 percent).

Were local government to fall short of its potential to address challenges and lift up communities, it risks becoming another symbol of a system that is failing a young generation

Many of those independent local councillors are young people who, for the first time since 2011, have a popular mandate to work for the betterment of their communities and bring the change they have been calling for. However, with thousands of new candidates, many young and with little previous experience, success will only come with support.

There are two ways, Tunisians told me on my recent visit, that the international community can respond immediately to these needs:

A potent antidote

Firstly, local councils can be 'twinned' with those in Western countries, enabling newly-elected Tunisian local officials to understand how local government works in other parts of the world, share best practices and develop lasting links that can serve their local communities.

Such initiatives would not require enormous financial investment, and with political will and a little coordination, Tunisia's local authorities could be twinned in no time.

Secondly, local councillors across the country would benefit from training programmes in different experiences of local government and management. With local councillors hungry to learn and eager to act, now is the time to respond.

Were local government to fall short of its potential to address challenges and lift up communities, it risks becoming another symbol of a system that is failing a young generation. Those young people who have participated will have little to show for it and few arguments to draw on to convince their peers to engage. Such an outcome would feed instability in a fragile country and would be a terrible waste of talent.

However, should Tunisia get this moment right, this first cohort of local government officials will provide an example to other young people in the country. They will show that political engagement is worth it and that local government can in fact work and change people's lives for the better. They can provide a potent antidote to the disillusionment, marginalisation and frustration that many young people face on a daily basis.

-Julian Weinberg is Political Dialogues Director, Forward Thinking

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Tunisian man draped in the national flag reads graffiti written in French, "Stay standing Tunisians", along Mohammed Bouazizi Avenue, in the impoverished central town of Sidi Bouzid, on 16 December 2013, where the self-immolation of a 26-year-old street vendor in December 2010 led to the uprising that forced veteran president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to flee the country (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.