Morsi myths: Re-examining justifications for Egypt’s coup

Two years ago, on 3 July 2013, swathes of Egyptian protesters received with joy the news that their military had granted their request to remove elected president Mohamed Morsi from office. Morsi, who hails from the Muslim Brotherhood, had only completed one year in office. Anti-Morsi protesters argued that Morsi was destroying the nation, necessitating an exceptional extra-democratic measure. Numerous Morsi mistakes notwithstanding, many of the justifications for Egypt’s military coup were based more on myth than reality.

Was Morsi a dictator?

One myth circulating widely around the time of Egypt’s coup was that Morsi had become a dictator no different from his predecessor Hosni Mubarak, who led Egypt for 30 years before being ousted in a popular uprising in 2011. As evidence for their claim, critics commonly pointed to Morsi’s contentious November 2012 decree that placed Morsi temporarily above judicial oversight and accusations that Egypt was being “Brotherhoodised” on his watch.

For multiple reasons, the claims that Morsi’s November 2012 decree qualified him as a dictator are unconvincing. First, Morsi’s decree was only temporary — it was active for only three weeks and was annulled a full seven months before the coup.

Second, from a purely political science perspective, Morsi’s policies did not closely resemble those of an autocrat. Shadi Hamid and Meredith Wheeler devoted an entire academic study to the topic. Their quantitative analysis concluded that Morsi was more democratic than most leaders of states in the midst of “societal transition”. Third, the decree was issued to jumpstart Egypt’s democratic transition - Morsi desired to hold parliamentary elections and hold a referendum on the nation’s new constitution.

Context is important to understanding the decree. Egypt’s judiciary is heavily politicised and had obstructed democratic movement during Egypt’s transition. In 2012, the judiciary disbanded Egypt’s first constituent assembly and first-ever democratically elected parliament. More importantly, just before Morsi issued his decree, Mubarak-appointed judges threatened to disband Egypt’s second constitutional assembly and rescind an earlier Morsi decree that effectively prevented the military from playing a dominant role in politics.

Failure to issue the decree, then, could have jeopardised the draft constitution, which was near-completion, and prevented parliamentary elections. Also, importantly, failure to issue the decree may have returned Egypt to quasi-military rule, where the president was little more than a puppet of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Harvard law professor Noah Feldman, University of Toronto law professor Mohammad Fadel and others defended the decree as essentially democratic. Morsi’s decree was mishandled from a public relations standpoint, but it did not make him a dictator.

Brotherhoodisation?

Like all elected leaders, Morsi had the right to appoint party members and others who could help him implement his political programme. Many in Egypt’s opposition, however, took issue with Morsi’s appointments of Brotherhood members, claiming that the appointments were evidence of the “Brotherhoodisation” of the nation. The “Brotherhoodisation” argument quickly took on a life of its own.

I’ve written elsewhere that claims of “Brotherhoodisation” were misplaced and exaggerated. Only 11 out of 35 Egyptian cabinet members and 10 of 27 governors were members of the Muslim Brotherhood. These are not absurd figures, especially given the Brotherhood’s electoral dominance and that Morsi had been facing regular overthrow threats (which, of course, culminated ultimately in an actual overthrow).

More importantly, from the very beginning of Morsi’s term, non-Islamist politicians systematically rejected participating in Morsi’s government. The long list of those who rejected positions included Nasserist politician and 2012 presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabbahi, who turned down Morsi’s offer to be his vice president, and April 6 Movement founder Ahmed Maher, who rejected a presidential advisor post. None of Egypt’s key state institutions - the military, police, judiciary, or media - had become “brotherhoodised.” Had they been, a military coup would not have been carried out so easily.

‘The Muslim Brotherhood constitution’

In December 2012, Egypt held a referendum on a new draft constitution, which was written by a democratically assembled body during the last half of 2012. Nearly 64 percent of voters approved the constitution and it was signed into law on 26 December, 2012.

A series of myths were produced both about the document itself and the process through which it was written. One major myth concerned the writing of the document - many in Egypt’s opposition believed that the Muslim Brotherhood wrote the document by itself. In fact, Egyptian independent media outlets often referred to the document as dustoor al-ikhwaan, or “The Brotherhood Constitution”.

The constitution building process was flawed, but not nearly as flawed as media outlets hostile to the Brotherhood suggested. It is true that the constituent assembly contained more Islamists than non-Islamists and that some of the non-Islamists withdrew from the assembly. But the withdrawals came late in the process, after writing was near completion. More substantively, the withdrawals were political and part of the larger attempt to suspend formal democratic procedure.

Those that withdrew from the assembly complained about the assembly’s composition. But the entirety of Egypt’s summer 2012 political spectrum — 22 Egyptian political parties in all — signed off on the assembly’s basic composition, which, in keeping with the results of several elections, was to include a slightly greater number of Islamists than non-Islamists. According to one liberal member of the assembly, Mohamed Mohie El-Din, non-Islamist complaints about (and withdrawals from) the assembly were driven mostly by politics, not substantive concerns about the composition of the assembly or constitutional draft content.

In terms of content, the document that was ultimately produced by the 2012 constitution-building process was far from perfect, but also hardly an Islamist manifesto. The constitution demanded regular presidential elections, term limits, political inclusion for all Egyptians, an impeachment article, and balance of power, among other things.

Concerns about Islamist influence were largely unfounded. Fears over Article 2 - which decreed that Islamic law would serve as the nation’s primary source of legislation - were mostly baseless. This article had already been part of Egypt’s constitution since 1971, and most Egyptians supported its inclusion. Tellingly, Egypt’s new post-Morsi constitution also includes the Islamic law provision.

Liberals also grumbled over Article 4 of the 2012 constitution, which gave Al-Azhar University scholars oversight on certain matters of Egyptian legislation. However, this article was not even suggested by an Islamist - it was suggested by a liberal member of the assembly as a way of protecting Egypt from an extreme application of Islamic law. Islamists merely agreed to the article’s inclusion. Also, at the behest of the four Egyptian Christian assembly members, an article exempting Christians and other non-Muslims from Islamic law was included. Mohie El-Din noted that this article was accepted by the assembly as is, word-for-word, and that none of the assembly members suggested it be removed even after all four Christian assembly members withdrew.

Morsi and the Brotherhood are not truly Egyptian

The Muslim Brotherhood was founded in Egypt in the 1920s and its members fought alongside other Egyptians against the British occupation and in several wars against Israel. In spite of their rather obvious Egyptian-ness, many Egyptians proclaimed in 2012 and 2013 that the Brotherhood is a disloyal, treasonous group. In fact, one well-known author claimed that the Brotherhood’s election constituted a “foreign occupation” of Egypt.

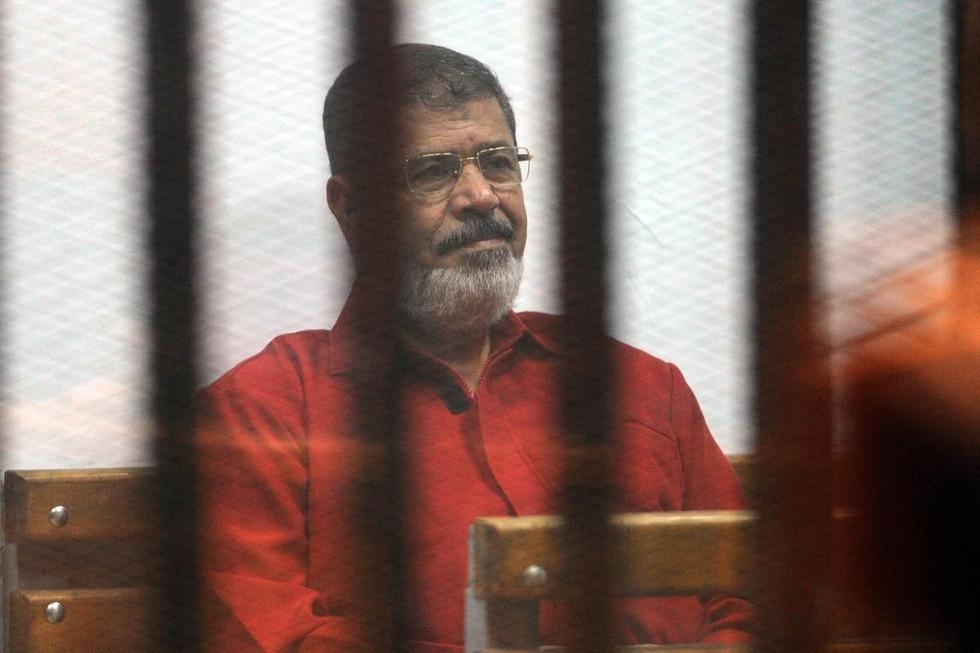

Speculation about the Brotherhood’s disloyalty to Egypt picked up during Morsi’s presidency. Newspaper articles and television news shows devoted considerable attention to Morsi’s allegedly close ties to Israel, Hezbollah, Hamas, Qatar and Iran. Importantly, many Egyptians view these varied political entities as enemies of Egypt. Actions by Morsi that would have been interpreted as normal diplomatic relations by a head of state in any established democracy were interpreted by anti-Morsi Egyptians as acts of treason. Given the extent to which the discussions about Morsi’s allegedly treasonous relationships took on a life of their own, it is not surprising that Morsi is currently on trial on espionage charges.

Mythical news stories were also produced about Morsi’s plans to sell the Great Pyramids of Giza and the Suez Canal - both sources of great pride for Egyptians - and give away the Sinai Peninsula to the Palestinians.

As evidence of Morsi’s allegedly disloyal nature, Egyptians pointed to Morsi’s speeches, which they argued provided important clues about his leanings. In particular, prominent media and political figures lamented Morsi’s use of the phrase “My family and my clan,” which they argued was a concealed reference to the Muslim Brotherhood and an indication that Morsi intended to exclude non-Brotherhood Egyptians from his political programme. As I argue in a chapter in a forthcoming book (edited by Dalia Fahmy and Daanish Faruqi, Oneworld Publications), an examination of Morsi’s presidential speeches reveals that Morsi did not once use the “my family and my tribe” phrase as an exclusive reference to the Muslim Brotherhood. His speeches, however, were edited and spliced on hostile television news programmes to make it appear as though he did.

Morsi’s first formal televised address was taken by anti-Brotherhood news outlets as one of the more prominent examples of Morsi’s alleged exclusionary intentions. Prominent television network OnTv edited segments of the speech to make it appear as though Morsi was using “my family and my clan” to address only Brotherhood members and exclude the rest of Egyptian society. However, a look at the entire speech makes it clear that Morsi included all Egyptians among his “family” and “clan.” He said:" O Great Egyptian people… you who are celebrating democracy today in Egypt... my beloved ones, my family and my clan, my brothers, my sons and daughters, you who are looking toward the future, and you who desire good, progress, growth, stability and safety for our nation of Egypt… all of my beloved ones…” Later in the speech, Morsi says: “I say to everyone [in Egypt], to all sections of Egyptian society, my family and my clan, I say to all [Egyptians] on this great day, that on this day, with your will and choice… I am a president for all Egyptians, regardless of where they are, inside of Egypt and outside of Egypt, in all of the governorates…”

‘The Nation’ did not reject Morsi

Egyptians who supported the large anti-Morsi protests held from June 30 2013 to July 3 2013 have greatly exaggerated the extent to which Egyptians opposed Morsi. Perhaps in an effort to justify extra-legal, extra-democratic procedure, Egyptian media and political figures referred to anti-Morsi protesters as “the nation” and argued that tens of millions of Egyptians had gathered in the streets to protest Morsi’s rule.

The popular 33 million estimate was convenient because, as was frequently pointed out in Egyptian media, that number represents a greater number than the total number of Egyptians who voted in the 2012 election that brought Morsi to office. The logic, explained ad nauseam, went something like this: because protest numbers were so extraordinarily large and represented a majority of Egypt’s 52 million electorate, it was acceptable to bypass procedural democracy in this one exceptional case.

Media figures Amr Adeeb, Lamis El-Hadidy, Mahmoud Saad, Youssef El-Husseiny and Khairy Ramadan, among others, asserted that more than 30 million Egyptian protesters had poured into the streets across the nation. Politician Naguib Sawiris argued that 30 million Egyptians had protested in Cairo alone. A Wall Street Journal op-ed written by a prominent Egyptian politician argued that the Brotherhood and Morsi possessed less than 1 percent support in Egypt. Media personality Reham Saeed recently upped the ante, claiming that there were 60 million Egyptian protesters in the streets in June and July 2013.

These cited protest figures represent logical and mathematical impossibilities. Tahrir Square, the site of the largest anti-Morsi protests, is the size of a small football stadium and cannot possibly contain millions of protesters. Between 30 June and 3 July 2013, there were about 20 protest sites across Egypt. Using crowd-sizing methodology - and assuming a generous estimate - there may have been between a million and 2 million Egyptians protesting (out of a total 84 million). The protests were large, but not nearly as large as was claimed - and they should not have been taken as a pretext to bypass formal elections.

Scientific polling data provide better indications of popular support. According to the only credible scientific polling data available, Morsi had more than 50 percent support among Egyptians before the coup and has maintained a support rating of more than 40 percent in the coup’s aftermath. This poll from Pew Research showed Morsi’s approval rating at 53 percent in the months preceding the coup, while this Zogby Research Services poll showed Morsi’s support rating at 42 percent as of September 2013, two months after the coup. A Spring 2014 Pew poll also showed Morsi with 42 percent approval among Egyptians, and reported that nearly half of Egyptians opposed the 2013 military takeover.

Conclusion

The myths presented here - along with other myths concerning the Brotherhood’s alleged opposition to the January 2011 uprising against Mubarak — provided ammunition for the June/July 2013 protest movement. Ultimately, and whether intentionally or not, these myths served as tools to steer Egypt far away from a democratic path.

The media and political figures who helped manufacture the myths were likely more terrified of electoral democracy than dictatorship. In post-Mubarak Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood had won five consecutive free and fair elections, with four of the elections being landslides. Egypt’s anti-Morsi opposition could have opted to wait a few months until parliamentary elections. If the opposition genuinely believed it had a majority, it could have taken a majority of parliamentary seats in those elections, had final say on who Egypt’s prime minister would have been, revised the constitution, and, if necessary, impeached Morsi using the 2012 constitution’s impeachment mechanism (as outlined in article 152). Instead of competing with the Brotherhood, however, Egypt’s anti-Brotherhood opposition chose to subvert established democratic rules and principles. Competition and democracy would have obviously been preferable.

At the time of Egypt’s 2013 military coup, there existed more than 40 registered Egyptian political parties, signs of legitimate political contestation, and indications that the Muslim Brotherhood was starting to lose public support as a result of clumsy policy and a series of mistakes and miscalculations. That constituted the perfect recipe for legitimate democratic change. Instead, Egypt’s anti-Morsi opposition chose to ignore domestic and international warnings about the dangers of a military takeover and bypass democracy altogether. Sadly, they, and all Egyptians, are now reaping the fruits of that decision.

An abbreviated version of this article was published in Al-Jazeera on July 1, 2015.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.