Netflix's Farha, a sea of orientalist tropes that says too little, too late

No sooner had the movie Farha hit Netflix than Israeli officials and hasbara propagandists were up in arms. Israel’s army of propagandists could not tolerate an honest depiction of the Nakba. More specifically, Zionist discontent seemed to focus on a poignant scene involving a horrific crime the titular character witnesses.

Although the film is about the Nakba, the Nakba as a deliberate event is absent throughout most of the film and only comes very late in the film’s narrative

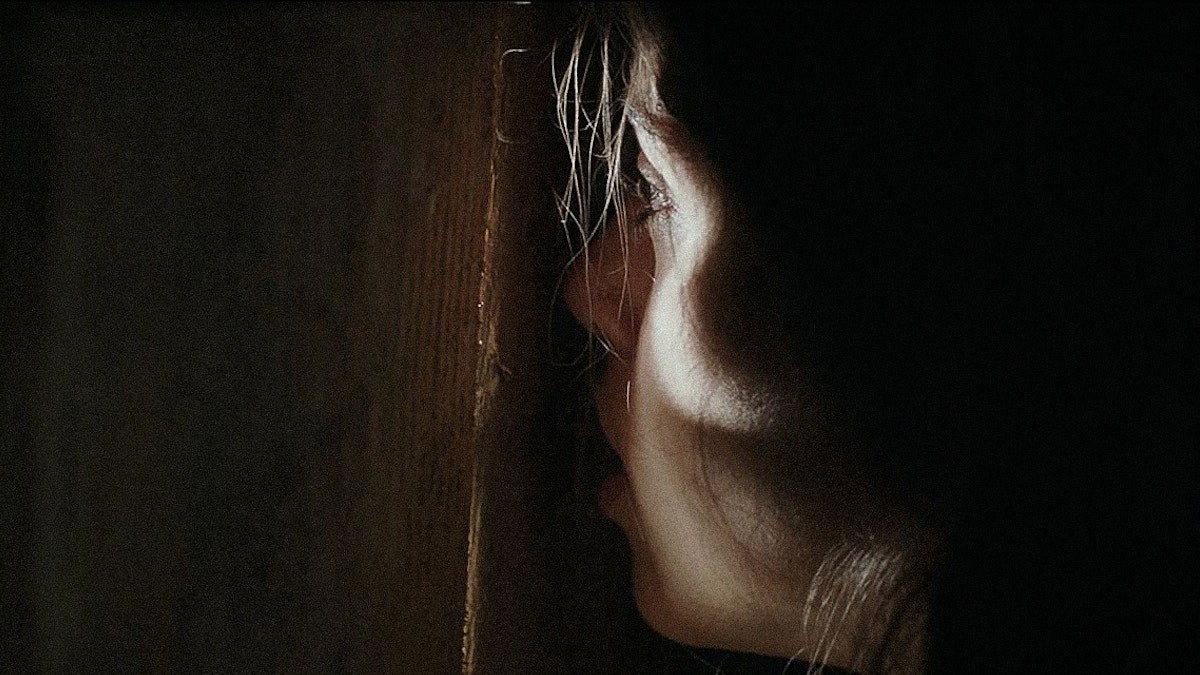

Farha, a teenage girl locked and hidden away by her father in the cellar of her home to protect her from Zionist militias, observes through a crack in the door the massacre of an entire Palestinian family (save an infant who is left to meet a harrowing slow death) at the hands of Zionist forces.

It is by now a well-established fact that such crimes took place during the war of 1948. Such events were saved not only in the Arab collective memory and Palestinian popular and oral histories, but also in the Israeli archive.

They were dug up by myriad Israeli historians. More recently, clips of Israeli documentaries where Israeli veterans jovially reminisce about the crimes they committed in 1948 resurfaced on social media.

If for Zionist apologists and hasbara propagandists the murder scene is shocking, it is not so because of any lack of evidence for what is presented, but rather, because it represents a truth that should not be told. Yet we are justified to think of this honest representation of one of the crimes that constituted the Nakba as actually too little, too late.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Absence of context

Although the film is about the Nakba, the Nakba as a deliberate event is absent throughout most of the film and only comes very late in the film’s narrative.

The film’s diegesis and the horrified gaze it casts from the confinement of the cellar inadvertently isolates the massacre of the family as a singular event, rather than emphasising it as part of an ongoing catastrophe.

Up until this moment, the Zionist forces remain largely unnamed. Conscious of how the western market treats the Nakba as a taboo, the filmmaker perhaps chose to soften the blow by limiting the depiction of Zionist crimes to this scene and postponing it until the viewers have already developed enough personal sympathy with the individual protagonist.

This led to a contrived and artificial dialogue that skirts around what it seeks to - and should in a realistic context - name. For example, the mayor, who happens to be the protagonist’s father, at one point exclaims that "the soldiers have entered the city" - not the Haganah, the Zionists, or the settlers; just a generic term that might as well apply to the Fedayeen (Palestinian fighters) whom the film already introduced as threatening figures, or the Arab armies that the mayor awaited in vain.

But the problem in the film's storytelling runs deeper than the bits of contrived dialogue. By absenting the political context, the film fails to build a strong narrative or situate the Nakba as the context for the crimes the viewer is about to observe, including who the perpetrators are and their motivations.

The behaviour of the Israeli soldiers makes sense, but only if we already know that this was part of an ongoing bloody campaign to establish a European-Jewish majority state and turn the inhabitants of the land into a minority.

Yet in the world of the film, the massacre appears as an abrupt event with nothing within the structure of the film to justify, explain, build up, or give meaning to this event. Here the filmmaker’s attempt to avert Zionist backlash backfires. It is the absence of context that makes it possible for Zionists to misconstrue the scene as a gratuitous "demonisation" of the Jewish gangs.

On the other hand, more forceful storytelling could have conveyed the motives and the context wherein such crimes were committed, not as anomalous events but as an ongoing campaign and governmental policy.

Visual Orientalism

Whereas the film inadvertently empties the Nakba from its specific political contents (down to the omission of the name of the village and the description of the assailants) to the extent that the plot at times rings like a generic story about the wartime plight of young women, the visual and cultural content is specific to a stereotypical representation of the Arab world.

The film presents its story through a sea of Orientalist stereotypes, from the wedding scene (a folkloric staple of films attempting to rehabilitate Palestine for a western-orientalist gaze) to the premise of a father locking his daughter up, to the dagger the father hands his daughter in a non-innocent nod to "honor killing".

There is a clear failure on the part of the director to tell her story without using the mainstream, visual, and narrative Orientalist lexicon.

Against this Orientalist backdrop, what could have been a gripping coming-of-age story in the time of war with a unique teenage and female perspective, ends up domesticating the story for the western, liberal gaze.

The story of a resolute rural girl with ambitions that her society cannot meet is relatable on many levels and for various reasons, including how modernisation favours urban centres at the expense of the countryside.

In the context of pre-1948 Palestine, it is even more relatable, as the conditions of the British occupation and Zionist settlements have further skewed economic conditions against Palestinian villages in a manner that disproportionately affected girls’ schooling.

The story, nevertheless, of a “feisty” girl that is an exception amongst her peers and who is pitted against her "traditional society" are clichés of western media which flirt with the presumptions of a western, liberal audience that wants to feel bad for little girls in other parts of the world while feeling good about themselves and their own conditions, and disguising this patriarchal sympathy and complacency as feminist solidarity.

Farha walks alone

Through absenting the political communitarian element, through pitting Farha against her people, and through the (otherwise skillful) use of the cellar-cum-prison cell as a narrative and cinematic device that isolates the girl from her community and from the larger events, the film flounders in its storytelling and undermines its own message.

The overuse of the locked room/prison cell as a narrative and cinematic device locks Farha away from the struggle of her people. This sets the stage for the kind of hyper-individualistic narrative that American liberalism encourages and promotes, and which obscures the horizon of common action and collective redemption.

The overuse of the locked room/prison cell as a narrative and cinematic device locks Farha away from the struggle of her people

The film’s protagonist, living through a microcosm of the Nakba yet isolated from the Nakba as collective suffering, finds redemption alone.

Nobody can save her: not her absent father, not the refugee family whom she asks for help, and not even the hooded informer who turns out to be her progressive uncle. Her only redemption comes from herself, and she is eventually capable of breaking the door of the pantry and walks alone to the Syrian border.

Farha’s final walk echoes the resolution of Mike Flanagan’s Gerald’s Game (which was also distributed by Netflix) especially in its post-climactic scene where the heroine’s inner voice tells her, after she walked away from her own traumatising confinement, that her strength comes only from herself.

Both clearly belong to the same genre where the audience can voyeuristically enjoy the perils of a confined woman and mask this masculinist- sometimes sadistic - joy, as feminist.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.