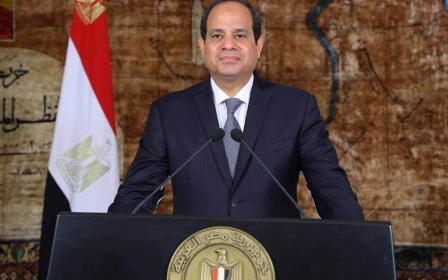

In Sisi’s Egypt, internet freedom is being shut down

Internet restrictions increased in Egypt during the recent constitutional referendum, which will allow President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to remain in office until 2030.

These restrictions followed an anti-Sisi online petition that had accumulated more than 60,000 signatures by 9 April. Given the country’s implementation of harsh social media laws last year, the latest developments raise concerns over Egypt’s growing tendency to restrict digital freedoms to suppress government dissent.

In light of the extension to Sisi’s presidency, it is likely that the digital rights of Egypt’s citizens will diminish even further, severely limiting their ability to express anti-government views.

Silencing opposition

Last month, 34,000 sites were blocked by Egyptian ISPs in an attempt to suppress the opposition campaign known as Batel (Arabic for “Void”). NetBlocks reported that 37.5 billion web links had also been broken as a result of the blocking of the Bitly URL shortening service.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The Batel petition was blocked at the IP-address level, but it was ultimately kept online through the creation of mirror sites, which helped it surpass 250,000 signatures.

The decision to block an entire IP address demonstrates a startling disregard for digital rights and freedoms, showing how easily technology can be manipulated by authorities to help advance their own political agendas, while stifling democracy.

Such excessive measures foreshadow a progressively restricted internet under Sisi

Under Egypt’s new social media laws, users with more 5,000 followers could face fines or be blocked if they are considered a “threat to national security”. Such excessive measures foreshadow a progressively restricted internet under Sisi, which is especially concerning given that he can now rule until 2030.

In blocking the petition contesting Sisi’s presidency, Egyptian authorities have actively worked to silence opposition and, in the process, infringed on citizens’ freedom of speech.

Quashing anti-government views

Egyptians have a right to express their political opinions. By blocking sites and introducing penalties for popular social media users, authorities are taking away this right and unfairly preventing criticism of the state.

Egypt is not the only country restricting internet freedoms to prevent dissent. Digital rights frequently fall by the wayside in countries such as Sudan, where site-blocking has been used to quash anti-government protests.

In Iran, social media platforms are frequently blocked amid anti-government protests, and Telegram - the most popular messaging service in the country - was permanently blocked in April 2018.

Arguably the figurehead for domestic surveillance and censorship, China carries out mass site blocking, with social media and global news sites rendered inaccessible.

Egypt will likely also intensify its campaign of blocking social media, particularly during times of unrest, which are inevitably on the horizon after April’s referendum result.

If harsher penalties are introduced for those seeking out or producing anti-Sisi material, self-censorship will become necessary for those wishing to stay off the government radar.

Fighting back

Though site-blocking may be enough to stop some users from accessing content, those who are determined enough can get around the blocks with relative ease. As shown with the Batel petition, site creators can produce mirror sites, allowing users to access their content after the original site is blocked.

VPNs also enable users to circumvent site blocks and are commonly used, even in heavily censored countries such as China. VPNs work by encrypting a user’s internet traffic to a remote server, making their activity unreadable to anyone who happens to be spying on their network. Connecting to a remote server also allows users to access geo-restricted and blocked content.

Egypt’s mass site-blocking during the referendum, and the arbitrary blocking of websites and social media users, suggests that further restrictions loom under Sisi's extended rule. This raises huge red flags over the future of digital rights and freedoms; the ability to access the internet and criticise the state are key components of a democracy.

Egyptians must stay vigilant and creative in order to make their voices heard and fight back against their increasingly authoritarian government.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.