Our son of a bitch: Is Sisi a good bet for Trump? Just ask Jimmy Carter

“Somoza is a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch,” President Franklin Roosevelt is alleged to have said in 1939. He was referring to the brutal Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza, an ally of what was then the world’s largest democracy then.

'Because of the great leadership of the Shah, Iran is an island of stability,' were the infamous words of Jimmy Carter in December 1977, a year before the Iranian revolution

Roosevelt’s words became a guiding policy for most Democratic and some Republican presidents throughout the rest of the 20th century and onwards. “Because of the great leadership of the Shah, Iran is an island of stability,” were the infamous words of Jimmy Carter in December 1977, a year before the Iranian revolution broke out.

The collapse of the Somoza and Shah regimes and the rise of anti-American regimes on their ashes did not prevent Barack Obama's Secretary of State John Kerry from confidently stating that the military was “restoring democracy” in Egypt, when it staged the country’s most brutal military coup in July 2013.

Values vs interests

These conflicting US policies persisted as a direct result of a perceived clash between values and interests. Based on it, three approaches to democratisation developed. The first, and most common, perceives democratisation as secondary, too costly, and less likely to succeed in the Middle East region. Still, it can be promoted with limited pressures, incentives and “advice”.

The rhetoric of the Trump administration runs directly against half a century of scholarly and policy conclusions: democratisation is 'only for the fools'

Carter and Obama’s policies followed that approach. The second approach reconciled values with interests by promoting the argument that democratisation serves the long-term security and economic interests of the United States. This was partly the approach of Harry Truman and George Bush Jr in his second term. It was the rationale behind the “Freedom Agenda”.

The third approach is embodied by the rhetoric of the Trump administration. It runs directly against half a century of scholarly and policy conclusions: democratisation is a liability, costly without benefits and, to put it simply, “only for the fools”. That – combined with the lavish praise of the likes of Putin and Sisi – is new in America.

'Ugly love-in'

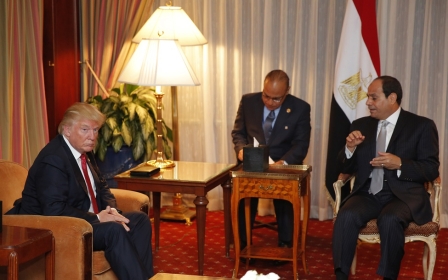

The first visit of Egypt’s military ruler to the White House this week (and don't miss these photos of it) was described as an "ugly love-in". Ugliness aside, it raises a main question: will the Trump administration meet the high hopes and demands of the Sisi regime? And if not, what are the ramifications?

Both leaders seem to agree that “the solution” to most of Egypt’s and the Middle East’s problems lie in the strongman’s iron fist, primarily against terrorists, insurgents, refugees, and perhaps against opposition and other “sources of instability”. The Devil, however, lies in the details, as the Arabic proverb says.

Egypt's not-so-free media has also been stoking anti-Americanism to a Bin-Laden-like level

The Sisi regime hopes for sustaining or increasing military and economic aid, for ignoring human rights violations outlined in the State Department’s annual human right report, and for designating the Muslim Brotherhood, the main Islamist opposition force whose affiliates won the last free and fair elections in the country, a foreign terrorist organisation (FTO).

But with the State Department’s 29 percent budget cut and the ongoing re-evaluation of aid to Egypt, it is difficult to understand how the first two objectives will be met, despite the love-in. The second and third objectives are not as straightforward.

The designation of the Muslim Brotherhood as an FTO is possible, but the resistance to such a move in policy, academic and bureaucratic circles may make it less easy. This is in addition to the disagreements with more critical allies than Egypt, such as Turkey, on that issue.

Value for money

More problematic for the Sisi regime is that the Trump administration will want to see value for money; more than $77bn in aid was given to the rulers of Egypt, mostly after the 1979 peace agreement with Israel. This probably means more involvement of the Egyptian military in the war against IS, and if needed, against Iran and its allies.

But these potential assignments do not take into account the military limitations and the political considerations of the regime.

More than $77 billion in aid was given to the rulers of Egypt, mostly after the 1979 peace agreement with Israel

Militarily, the regime has failed to quell a limited insurgency in the non-rugged, coastal parts of northeastern Sinai, where the manpower ratios exceed 100 soldiers to one insurgent. It has failed to win, despite four years of brutal violations of almost every moral law of warfare cited in the Egyptian Constitution and the Geneva Conventions.

In Egypt, the military and security forces have a better record of killing unarmed local protestors, than combating any armed state or non-state actor.

Values and morality aside, the “our SOB” policy may be beneficial to US interests in the short- to medium term (one or more presidential terms).

In the long term, it spelled and will probably continue to spell disaster. In the specific case of Egypt, the “maybe beneficial” can turn to “problematic” given the level of incompetence of the regime; whose leader endorsed a device that can cure the AIDS virus and turn it into a minced meatball sandwich.

- Dr Omar Ashour is a senior lecturer in Security Studies and Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter. He can be reached at [email protected] or @DrOmarAshour

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (L) and US President Donald Trump walk through the colonnade of the White House to a lunch after a meeting on April 3, 2017 in Washington DC. (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.