Pakistan: What comes next in the Imran Khan saga?

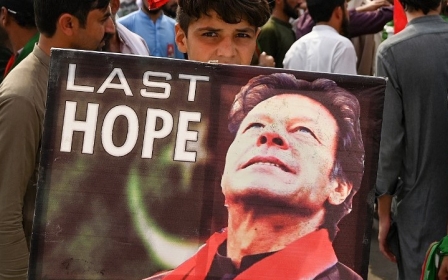

The dramatic arrest and swift release of former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan this month marked the culmination of a high-stakes political game - one that has left people wondering what comes next.

After Khan was hauled away by paramilitary troops on 9 May from an Islamabad court, where he had appeared to face corruption charges, his supporters took to the streets in protest, blocking traffic, setting buildings ablaze and targeting military facilities. More than 10 people died amid clashes between protesters and police, while at least 2,000 were arrested.

Amid this backdrop, the absence of governance was concerning - and to make matters worse, the interior ministry ordered the suspension of communication services. The apparent lack of official control as protesters targeted military zones led to rumours of division within the army’s ranks over Khan’s arrest, although these rumours were quickly rejected by a spokesperson.

More surprising was the Supreme Court’s hurried decision in less than three days to declare Khan’s arrest unlawful and to order his immediate release. Khan was then permitted to leave for his Lahore residence, where supporters gave him a hero’s welcome.

This suggests that legal decisions, along with governance and administration in Pakistan, are being handled on an ad-hoc basis when it comes to Khan, drawing attention to how the country’s non-democratic elites have been inflicting disorder in an effort to bolster their own power.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Undoubtedly, Pakistan’s military is the country’s most powerful institution, having ruled the nation either directly or indirectly for decades. All political parties in Pakistan are extensions of this ruling order.

While patronising this compromised form of parliamentary democracy, military generals have had no qualms about destroying politicians who become a threat to their supremacy. In the late 1970s, the army deposed former civilian Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was executed soon thereafter. His daughter, former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, was later assassinated during the regime of dictator Pervez Musharraf.

Facade of democracy

For decades, the ruling order has allowed Pakistan’s generals to conceal their ultimate authority behind the institutional supremacy of the state, while using democracy merely as a facade. But Pakistan’s cooperation with the US in the post-9/11 “war on terror” necessitated a change.

As a charismatic cricket legend, Khan launched his party in the mid-1990s, but he ultimately rode to prominence on the back of his ambivalent opposition to the war. A web of “counterterrorism” operations ostensibly aimed at eliminating Islamist militants proved counterproductive. In western media parlance, Pakistan’s pro-Taliban policies comprised a “double game”.

Pakistan's economy was never good, but a fractious political environment in the 'new Pakistan' exacerbated the situation

While opposing the war, Khan became closer to the Pakistani military, and also gained the moniker “Taliban Khan”. This initially played well with the middle-class morality of the country’s urban youth, to whom the war didn’t matter much, as long as its destructive effects were restricted to the margins. It played even better when those effects, in the form of escalating insecurity and soaring inflation, began permeating major cities.

Khan’s supporters sought a reformed Pakistan. With the help of the powerful urban middle classes, Khan was essential to the military’s strategy to reform the “old” order of legacy politics.

As a result, the phrase “new Pakistan” became a theme around which the state, led by the military, vowed to eradicate the corrupt past. During the 2010s, Khan’s popularity grew as he projected himself as a corruption fighter and trustworthy replacement for the then-incumbent prime minister, Nawaz Sharif.

The peak of “project Imran Khan” came in 2016, when General Qamar Javed Bajwa became army chief. In the months that followed, Sharif was removed from office after a legal verdict on corruption charges, indicating which way the winds would blow in the 2018 general elections. Political “turncoats” started joining Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. Upon his subsequent electoral victory, legacy parties did not wholeheartedly embrace Khan’s “new Pakistan”, while he accused them of corruption.

Self-destructive path

When Khan was removed from office in a no-confidence vote last year, it was evident that the military and its institutions had started to tread a self-destructive path. Pakistan’s economy was never good, but a fractious political environment in the “new Pakistan” exacerbated the situation.

Amid soaring inflation, a lack of foreign investment and a delayed bailout from the International Monetary Fund, millions more people have been plunged into poverty. While Khan took office on a vow to purge the country of corruption, his target was selective: Sharif and his ilk. Other issues were swept under the carpet, as long as Khan’s own relationship with the military remained good.

Khan’s current political quandary is the outcome of his misperception that he is significantly different from other politicians in Pakistan, and that the military should thus deal with him preferentially.

Still, credit must be given where it is due: Khan used the tools provided by powerful institutions to gain access to the urban middle classes, with their wide overseas connections - but by retaining their fervent support, he ultimately became a thorn in the side of these same elite institutions.

As some retired generals have come out publicly in support of Khan, the lack of action against the former prime minister is being widely viewed as the outcome of divisions within the state. But which side in this political impasse will ultimately win? Could martial law be imposed again, or will the ongoing turmoil continue to fuel more spectacles?

Because its institutional esteem is at an all-time low, military rule is not an option, nor could it keep the nation united. Reconciliation is the only available option. But Khan seems hardly prepared to sit with other political parties, which calls into question how he can manage this critical opening. And the rest of the world will not sit idly by as a nuclear-armed nation sinks.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.