Sharia law will play a greater role in Syria's future

Syria’s raging civil war has led to an absence of legitimate judicial entities. In rebel-held areas various factions have implemented Sharia law in order to organise public life. The emergent Sharia courts are dominated by different factions who run them based on their own interpretation of Islam and political objectives. Hence, Sharia law and the calls for a greater presence of Islam in a future Syria are often met with great scepticism.

The implementation of Sharia law is widely associated with oppression, backwardness and severed hands. But as usual, things are not that simple. Actually, Islamic law offers the potential for fairness and justice. Its enormous possibilities for interpretation are a blessing and a curse at the same time. Blessing, because it allows continuous development through a diversified discourse. Curse, because it is interwoven with political dynamics and thus easy to exploit.

However, leaving the sovereignty of interpretation to radicals in war zones is dangerous, as Islam and its law will undoubtedly play a determining role in parts of Syria in the future. Instead, a deeper understanding of Islamic law’s potential is crucial in order to not condemn something that is of utmost importance for millions of Syrians and to comprehend the political dynamics that concern both the country and the whole region.

The ambiguity in Islamic law

Islamic law is often pictured as a static system of rules. But as in every law, it is dependent on the political surroundings, social climate and the spirit of the times. Moreover, due to technicalities of getting to a judgment ("hukm"), differences in opinion are inherent in the system of Islamic law. Contrary to Western approaches where - especially since the Enlightenment era - the aim has been to carve out the one truth, the tradition of Islamic law endorses the simultaneous existence of different interpretations and therefore multiple truths.

Thomas Bauer, professor of Islamic studies at the University of Munster, accredits this approach to a high tolerance of "ambiguity". To arrive at a judgment, the Islamic jurist reverts to various elements. The Quran and the Hadith lead to an indication ("dalil") which then is completed by analogies, common law and aspects like the common good. Obviously, the resulting judgment can vary significantly. That is why a plurality of opinions is required as the product of more opinions increases the chance of fulfilling the "divine will".

Of course, people need some kind of legal certainty and so a certain interpretation is usually recommended. Nevertheless, those interpretations have no claim to an absolute truth and thus offer room for change and flexibility. Given the absence of law and order in Syria’s rebel-held areas, people tend to revert to the common law that in turn is directly inspired by the tradition of Islamic law. Thus, Sharia courts are appreciated by many locals as a common denominator in turbulent times.

In Middle Eastern countries, Sharia-based or influenced state laws are more the rule than the exception. Jordan has both civil and Sharia courts whereby, for example, the latter are competent for personal status law. Even in Lebanon, a country with high religious and ethnic diversity, the legal system is influenced by Sharia law. Similar to Jordan, the personal status law of Muslims falls under the jurisdiction of Sharia.

Saudi Arabia claims to apply Sharia law completely and is often portrayed as the incarnation of an injustice system that results from the Sharia’s alleged inhumane essence. Ironically, methods like torture and closed-door trials contradict Islamic legal principles and reveal the kingdom’s political institutions that outweighs religious motivations.

However, Western law is also based on biblical teachings to some extent. The preamble of the German Basic Law refers to the "responsibility before God" and, for instance, German law safeguards the protection of marriage and recognises Sunday as a day of rest. These examples show that religion historically affects societies and hence their state laws, even if the particular system defines itself as secular.

The hijacking of a tradition by an authoritarian regime

The Syrian constitution from 1973 also declares Islamic jurisprudence as one main source of legislation. In practice, Islam and Islamic law have been standardised and have lost their emancipatory potential. The office of Syria’s Grand Mufti undermined the traditional function of Islamic scholars as a counterbalance to the authorities and their arbitrariness.

Grand Mufti Ahmed Muhammad Amin Kuftaro got a seat in the Syrian parliament one year after Hafez al-Assad took over power in 1970. He was close to the regime and declared the president’s re-election in 1991 a national and religious obligation. After the US-invasion of Iraq in 2003 he also propagated the fight against the occupiers as jihad. The complex system of Islamic law became institutionalised as a part of Assad’s establishment and left no room for ambiguity or flexibility. As a result, Sunni Islam was disconnected from the state and developed into a sphere of resistance.

In general, a situation of insecurity and injustice spurs radical currents who dislike ambiguity and instead prefer to propagate one truth to spread their ideology and suppress dissidence. Syria’s civil war has led to a state of utter insecurity where justice is almost impossible to even think of. Therefore, Sharia courts that emerge in Syria’s war should be carefully considered. Neither should they be regarded as representative of Islamic Law in general - because there is no such thing - nor should they be equated with the rebel factions who influence them. Reports of torture and intimidation rather illustrate the abuse of Islamic law. Ultimately, all laws - including "secular" ones - can be abused depending on the social and political environment.

Uncertain outcome

Present concepts of statehood and the corresponding institutions are likely to be dysfunctional in the Syrian case. The status of Islam in general is still an open topic in the Middle East and has so far manifested itself in various ways: from Saudi Arabia where a tribe used the radical Wahhabi interpretation of Islam to establish a kingdom, to Egypt where a military regime stifles Islam in order to secure its power.

Forecasting the development of the situation in Syria is speculative at best. One thing, however, is certain: Islam will play a greater role. Therefore, it is advisable to understand the inherent potential of Islamic law and try to improve the environment to fulfil it.

- Lars Hauch studied International Development in Vienna and worked as head of editorial at the German media outlet Commentarist. With a focus on the MENA region, he published a commented roundup www.menaroundup.com, in addition to writing for EAWorldview and the German CARTA.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

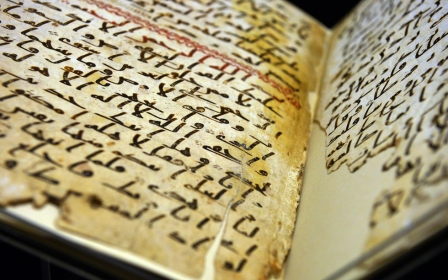

Photo: Syrian Muslim man reads the Quran, Islam's holy book, at a mosque in Kafr Batna, in the rebel-held Eastern Ghouta area, on the outskirts of the capital Damascus, on 6 June, 2016, on the first day of the holy month of Ramadan (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.