Sisi's blame-shifting perpetuates instability in Egypt

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi continues to deflect responsibility for Egypt’s problems. In an interview with an Italian newspaper on 16 March, Sisi suggested that the January torture and murder of Italian graduate student Giulio Regeni may have been carried out by Sisi’s political enemies. He implied they did so to destabilise both Egypt and relations with Italy.

"The timing of this incident is intriguing and raises several questions. Are there any beneficiaries who seek to impede relations, given the turbulent situation in the region?" he said.

Sisi’s remarks are consistent with Egypt’s recent policy of denial and blame-shifting. Rather than own up to government-perpetrated atrocities and seek corrective action, the authorities have consistently thrown out wild conspiracies to explain away human rights abuses.

I've documented elsewhere the Egyptian government’s repeated pattern of justification, outright denial and conspiratorial thinking. Most recently, after the European parliament passed a resolution condemning Egypt in the aftermath of Regeni’s murder, Egyptian politicians suggested that the now-outlawed Muslim Brotherhood had bribed European politicians to pass the resolution.

The deflect and deny policy is dangerous for Egypt, in part because it prevents the government from accepting responsibility for policies that are undermining the country’s stability. The government continues to view itself as a victim of both an international conspiracy and local attempts by extremists to undermine its rule.

The irony is that owning up to government-perpetrated abuses would likely help Egypt gain both international goodwill and fight offshoots of the Islamic State at home.

The Guardian reported that Sisi’s comments to the Italian newspaper appeared to be a desperate move to appease the European parliament. In comments clearly directed at European political leaders, Sisi, as he has so often done, played the “terrorism" card.

"There are 90 million people living in Egypt," he said. "Imagine if just one in a thousand of these young people become radicalised and were recruited by terrorists."

This appeal to European authorities is misguided at best, dishonest at worst. Political scientists have long observed that the Egyptian government’s authoritarian policies have contributed directly to radicalisation in Egypt, something Sisi is either unable to grasp or reluctant to admit.

Since the 2013 military coup through which Sisi took power, terrorism has increased manifold in Egypt. Previously obscure groups have grown into powerful IS affiliates, and carried out dozens of attacks in the country.

All of this is tragic, but not particularly surprising. The heavy handedness of military authoritarianism alienates, excludes and inevitably drives some toward radicalisation.

Immediately after the 2013 coup - as Egypt’s military government was arresting opposition political leaders, banning political parties, shutting down television networks and shooting protesters - scholars predicted precisely what has since unfolded in Egypt.

At that time, Professor John Esposito wrote: "The [Egyptian] military’s purpose is transparent and in line with the modus operandi of [the Egyptian government] for decades: use brute force to intimidate, repress, and provoke the opposition to violence and then say, ‘Look I told you they were wolves in sheep’s clothing'."

Scholar Shadi Hamid, meanwhile, argued that the demotion of democracy and the resurgence of military rule would "breathe new life into the ideological claims of radicals".

Two months after the coup, Professor Khaled Abou El Fadl wrote: “The invariable and predictable result is that [authoritarianism] leads to the radicalisation of the Islamists who lose trust in the lofty principles of democracy and human rights."

Since the summer of 2013, Egypt has used its security apparatus to eliminate political opposition. Egyptian police have killed more than 2,000 protesters and arrested more than 40,000 people, most on non-violent, politically motivated charges.

In January, Egypt’s Nadim Centre for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture documented 700 cases of torture and the deaths of 474 Egyptians while in police custody - in 2015 alone.

Shortly after the report was released, Egyptian authorities announced the centre would be shut down. An Egyptian Rights group also documented more than 1,800 cases of forced disappearance in 2015 alone.

These are typical byproducts of military takeovers, and precisely the kinds of things political scientists warned about in July 2013.

A bold stance by Sisi to create independent fact-finding committees to investigate not only Regeni’s murder, but also numerous mass killings of supporters of deposed president Mohamed Morsi, could go a long way toward improving Egypt’s international image.

Additionally, releasing political prisoners and reinstating banned political groups might help stem the tide of radicalisation.

Bold moves like these are highly unlikely, however. Too many government officials would be scared that such transparency could lead to criminal charges against them.

Moreover, and in any case, Sisi has, from the start of his political career, arguably demonstrated a deep lack of awareness of his own role in perpetuating Egypt’s problems.

As Rania al-Malky has recently explained, Sisi has often implied that he is a gift to the nation, that he is doing a wonderful job, and that it is Egyptian common people who are to blame for Egypt’s woes because they are falling short of his high standard.

More likely than an about-face from Sisi, then, are more denials, blame-shifting and conspiracy theories. Unfortunately for Egyptians struggling through a worsening economy, government blame-shifting won’t help dig their country out of the problems its military and police have dragged it into.

- Dr Mohamad Elmasry is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communications at the University of North Alabama.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

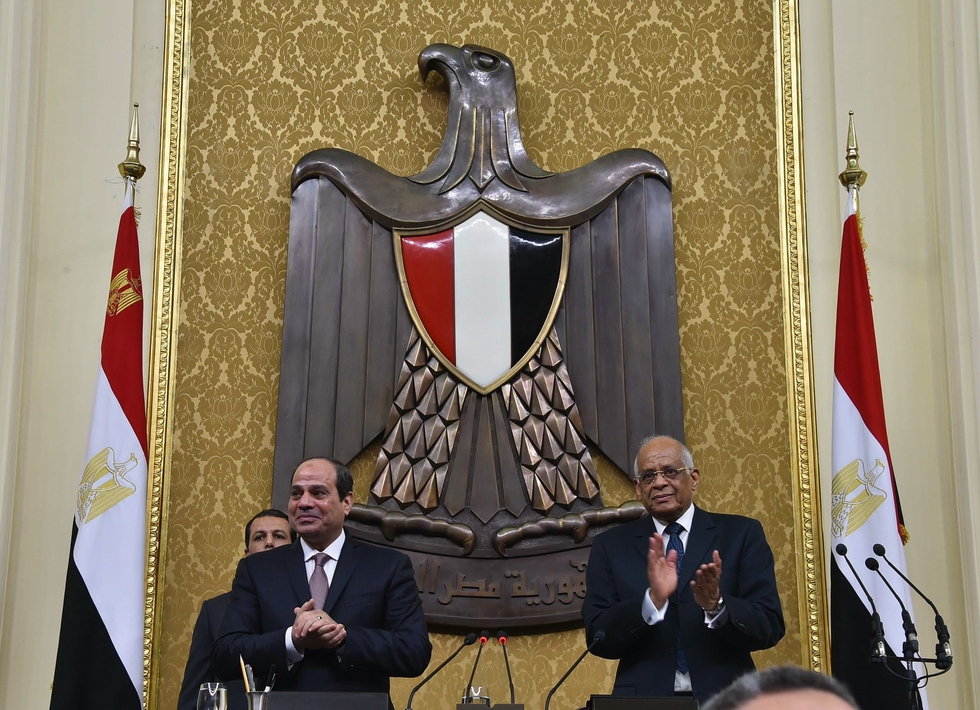

Photo: Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi (L) and Ali Abdel-Al, speaker of Egypt’s parliament, during the former's visit to the parliament headquarters in Cairo on 13 February, 2016 (AFP/HO/EGYPTIAN PRESIDENCY).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.