Spectre of Chernobyl hangs over Middle East’s nuclear ambitions

The Middle East is going nuclear.

The United Arab Emirates is home to the Barakah nuclear power station, the Arab world’s first such facility and the biggest nuclear power plant currently under construction.

Saudi Arabia has plans for two large nuclear plants to cope with national energy demands, increasing by more than eight percent annually.

Initial land-clearing work has also begun for a nuclear facility at Akkuyu, on Turkey’s southern coast, while Egypt is due to start building a nuclear power plant in El Dabaa, west of Alexandria, next year. Jordan has plans for a number of smaller nuclear facilities.

A poisoned legacy

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Nuclear power has considerable advantages over other fuels. A single nuclear facility can produce enormous amounts of energy, and nuclear is a clean source of power; unlike coal, oil or gas, it does not produce climate-changing carbon emissions.

Weighed against this is the mind-boggling expense of going nuclear. The Barakah facility, expected to supply a quarter of the UAE’s energy needs, will cost upwards of $30bn.

Although safety features and procedures at nuclear facilities have been improved, we’re still just as far from taming nuclear reactions as we were in 1986

Equally expensive is the cost of decommissioning a nuclear plant at the end of its working life. Nuclear power has been around for more than 60 years, but no one has really come to grips with how to dispose of spent but still highly dangerous nuclear waste, handing a poisoned legacy to future generations.

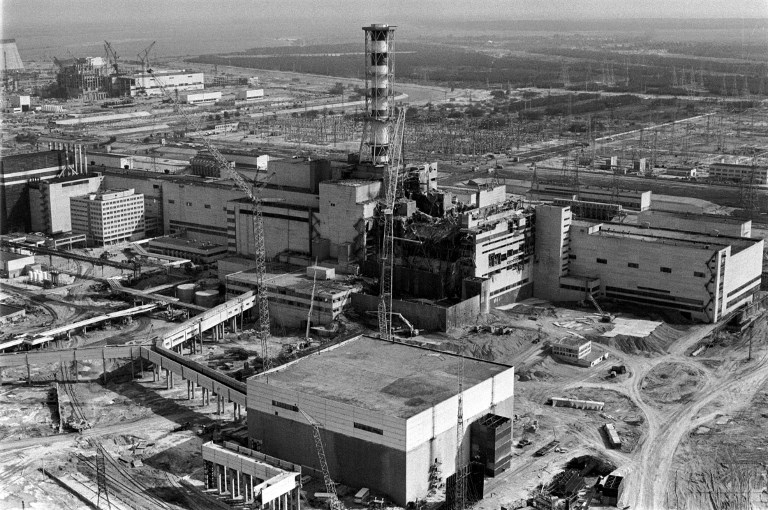

And then there is the safety factor. On the morning of 26 April 1986, engineers at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine were carrying out routine turbine and reactor tests when they heard a sudden roar, followed by a loud blast.

Some thought there had been an earthquake. In a recently published book on Chernobyl, Serhii Plokhy - now a history professor at Harvard but in 1986 a Ukraine resident - said the idea of a nuclear accident was inconceivable. "As far as they [the engineers] were concerned, the reactor and its panoply of safety systems were idiot proof. No textbook they had ever read suggested that reactors could explode.”

Obsessed with secrecy

The nuclear industry today - whether in Russia, Europe, China, the US or the Middle East - is similarly confident of its safety.

Chernobyl’s reactor exploded, throwing vast clouds of radiation up into the atmosphere that were blown by winds over Scandinavia, much of Europe and Ukraine itself. Plokhy’s book - billed as the most extensively researched work yet on the Chernobyl disaster - should be required reading for any government official contemplating a nuclear-driven future.

He said that although safety features and procedures at nuclear facilities have been improved, we’re still just as far from taming nuclear reactions as we were in 1986. Lessons have not been learned.

The nuclear power industry, which grew out of and alongside nuclear arms programmes, continues to be obsessed with secrecy, and has always been wary of disclosing any problems. In 1957, there was a serious accident at a Soviet nuclear power plant in the Urals. Both the Soviets and the US military - which was aware of the incident - decided not to disclose the event to the public in the West.

"Both sides had a stake in keeping it under wraps so as not to frighten their citizens and make them reject nuclear power as a source of cheap energy," Plokhy said.

Safety concerns

Plokhy says a combination of factors was to blame for events at Chernobyl, which beyond the immediate deaths, is believed to be responsible for tens of thousands of cases of fatal diseases, such as cancer. There were shortcuts in construction and pressure to increase energy quotas. Testing procedures were not followed. There were serious design faults, yet staff who foresaw dangers were afraid to speak out for fear of losing their jobs.

Plokhy foresees similar consequences in modern-day nuclear power programmes, wondering whether safety measures will be followed scrupulously in countries such as Egypt, the UAE and Pakistan.

"Are we sure that all these reactors are sound, that safety measures will be followed to the letter, and that the autocratic regimes running most of these countries will not sacrifice the safety of their people and the world as a whole to get extra energy and cash to build up their military, ensure rapid economic development, and try to head off public discontent?” he said. “That is exactly what happened in the Soviet Union back in 1986.”

Of course, these are early days in the nuclear power industry in the Middle East, but already there are problems. The first reactor unit of the four being built at the Barakah plant in Abu Dhabi was supposed to have come on-stream in 2017, but there is reportedly evidence of cracks in some of the containment walls and delays due to shortages of trained staff.

On Wednesday, Qatar asked the United Nations' nuclear watchdog to intervene in a dispute over a a nuclear power plant that is under construction in the United Arab Emirates, Reuters reported.

Citing a letter Qatar sent to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the news agency said that Doha argued that Barakah, a nuclear plant being built near its border with the UAE, threatens the stability of the region and the environment.

Qatar said that a radioactive plume from an accidental discharge could reach its capital Doha in five to 13 hours, while a radiation leak would have a devastating effect on the region's water supply because of its reliance on desalination plants.

The biggest prize

Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear corporation, is developing Egypt’s 4.8GW nuclear power plant, with work due to start next year. But there have been a number of protests at the site of the proposed plant, just as there have been demonstrations as building work gets underway at Turkey’s Akkuyu nuclear facility, also being built by Rosatom.

In Jordan, the government seems to have abandoned plans for a $10bn nuclear plant to be built by Rosatom due to worries over costs. Instead, Amman is planning to build a number of much smaller reactors.

Nuclear power may be a solution to chronic energy shortages in many Middle East countries, but it also could cause a Chernobyl-style catastrophe

At the same time, the nuclear industry is falling over itself for what’s considered the biggest prize of all: Saudi Arabia. Competition for building the first two reactors in the kingdom’s ambitious nuclear power programme is intense, with US, Chinese, South Korean and French companies, along with Rosatom, involved in the process.

The US Congress is investigating reports that the White House has been transferring sensitive nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia so that US firms allegedly linked to President Donald Trump could win multibillion-dollar nuclear contracts.

Congress members say such actions would violate US laws preventing the export of technology that could be used in nuclear weapons development. It could also prompt a regional nuclear arms race.

Meanwhile, Iran says the reported nuclear technology transfers are evidence of the hypocrisy of the Trump administration.

Regional volatility

Above all, nuclear power needs stability and systems where everyone works together. The Middle East is one of the world’s most volatile regions, full of rivalries between states and internal divisions.

Israel has never disclosed the full extent of its nuclear programme and, in the past, has launched air strikes on nuclear facilities in both Iraq and Syria. There are ongoing arguments over the status of Iran’s nuclear industry.

Nuclear power may be a solution to chronic energy shortages in many Middle East countries, but it also could cause a Chernobyl-style catastrophe in the region.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.