Terrorism and paintings in the Sahara

Two recent statements on the increasingly chaotic state of much of North Africa and the Sahel cannot pass without comment.

On 3 June, Algerian Foreign Minister Ramtane Lamamra told a strategic forum on "transnational threats" in North Africa, held in Algiers and sponsored by a US Defence Department think-tank, that “the Arab Spring [had] allowed local terrorist groups to increase their ideological influence and power”. The Arab Spring, he said, had promoted the rise of "terrorist" groups.

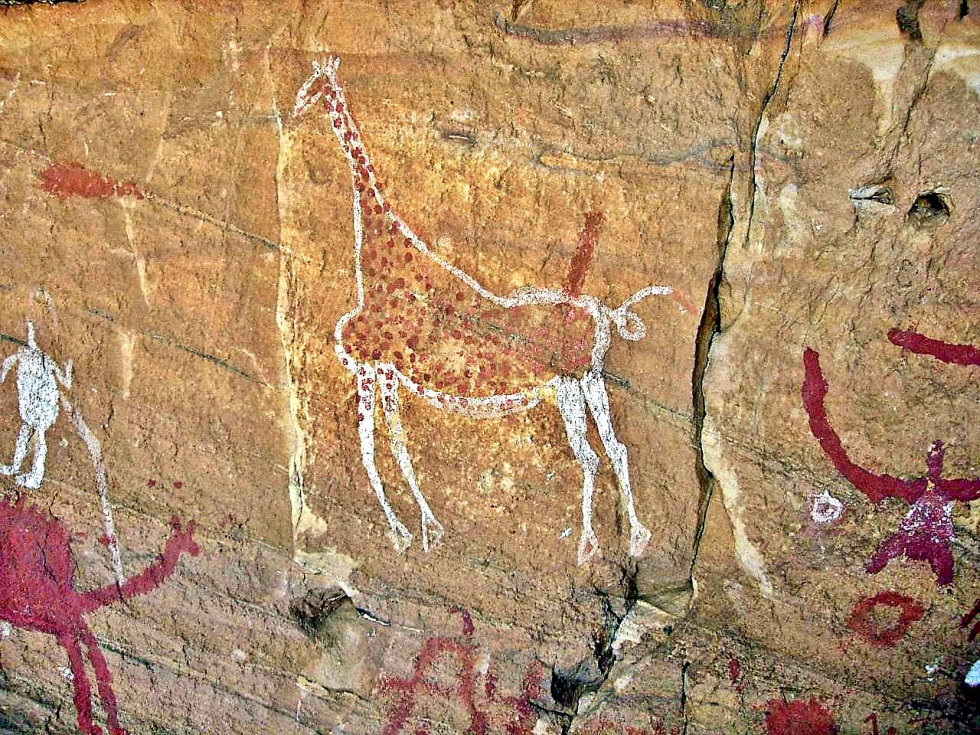

On the same day, Reuters ran a story saying that vandals had “destroyed prehistoric rock art in Libya's lawless Sahara”. It said that the destruction accelerated during the “armed anarchy” that has swept across the country since the ousting of the Muammar Gaddafi regime in 2011. Reuters was referring to the vandalisation of many of the thousands of magnificent prehistoric paintings in the UNESCO-designated World Heritage site of the Acacus Mountains in SW Libya.

Both statements were grotesque: Lamamra’s as a political perversion of the North African situation; the news agency’s story as a poignant reminder of one of the many tragedies of that situation.

Lamamra was, of course, saying what his sponsors wanted to hear. And, by and large, he was correct in saying that “terrorist” threats in the region have become more complicated and transnational. Some would also agree that he has a point, especially in so far as the Libyan “space” has provided many of these so-called “terrorist” groups with a safe haven. However, a very large footnote should be added to point out that this “space” is the consequence of NATO’s ill-planned intervention in Libya, not the Arab Spring as Lamamra and Washington would have us believe.

It might also be added that one of the causes of the Arab Spring in North Africa was Washington’s launch of a “second” or “Saharan” front in its global war on terror. Counter-terrorism simply became a euphemism of the region’s autocratic states for the increased repression of their long-suffering citizens. As a prominent civil society leader explained: “They [the Algerian regime] have become even bigger bullies now they know they have the Americans behind them.”

Indeed, both Lamamra and the Pentagon should be careful when talking about “terrorism” in North Africa, because, no matter how one defines and approaches the subject, the major form of terrorism in North Africa is “state terrorism”, with Algeria’s own Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité (DRS) being the region’s lead player.

As for the “terrorism” that the Algiers forum was addressing, Lamamra knows as my books argue that the DRS has controlled, at least did until very recently, the leadership of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and most of its regional offshoots through its successful infiltration of DRS agents into those groups.

Most of the region’s several “false flag” terrorist operations, notably the 2003 kidnapping of 32 European tourists, were undertaken by the DRS with the knowledge and complicity of US intelligence services. Indeed, Mohamed Lamine Bouchneb, the leader of the “terrorist” attack on the Tiguentourine (In Amenas) gas facility in January 2013, had been running DRS “false flag” operations in that corner of the Sahara for the best part of a decade.

A few other footnotes should be added to Lamamra’s speech to set the record straight, namely that the DRS also:

Ran the main al-Qaeda training camp in the Sahara; thus playing a major role in the spread of terrorism throughout North Africa and the Middle East;

Gave strong support to the Gaddafi regime during 2011, thus delaying its overthrow and contributing to the extent of the violence and subsequent chaos;

Supported the three main Islamist “terrorist” groups of AQIM, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa and Ansar al-Din in their takeover of northern Mali (Azawad) in 2012.

The Reuters article is not entirely unrelated to Lamamra’s assessment of North African terrorism. Although little more than a passing comment on the scene, it is a timely warning as to what might be happening to some of the world’s most important prehistoric heritage. I emphasise the words “might be”, simply because we do not know precisely what is happening in these remote regions.

Some of the paintings in Libya’s Acacus Mountains and Algeria’s adjoining Tassili-n-Ajjer date back 12,000 years, which is why UNESCO designated both the Acacus Tassili-n-Ajjer as World Heritage Sites.

Having survived the vicissitudes of the Sahara for thousands of years, the last 60 or so years have seen this heritage under attack from a myriad of causes.

First came the European “discoverers”. In the Tassili, this was France’s infamous Henri Lhote, who actually hacked out rock art panels and “stole” literally thousands of artefacts for his personal collection. He even oversaw the painting of at least a dozen “fakes”, now mostly identified by Algeria’s Malika Hachid. The Acacus fared better, thanks to the more scientific approach of Italy’s Fabrizio Mori.

Then came the tourists, mostly ignorant of the damage they were doing to the paintings by washing and photographing them. And, with few local controls, what was wrong in “collecting” or buying “little souvenirs”?

Sanctions against Libya and Algeria’s “civil war” (Dirty War) of the 1990s brought a temporary halt to tourism and gave the paintings a decade of respite. But, with the reopening of the Sahara in the late 1990s, professional “looters”, mostly from Germany, began plundering the Sahara on a commercial basis. Their actions were finally curtailed by a combination of draconian actions by the Algerian authorities and the restrictions on Saharan travel following the onset of the “terrorism” that Lamamra is so concerned about.

However, this renewed “closure” of the Sahara has brought a new threat to the paintings. Many Islamic fundamentalists see them as idolatrous. In the first few years of this millennium, I was findings paintings in which human heads had been removed or otherwise destroyed. Local people, fearing “Islamist retribution”, explained the vandalism as the work of children.

Now, it seems, the many hundreds of Islamist “terrorists”, so-called “jihadists”, who are traversing the Tassili-n-Ajjer and hiding out in the rabbit-warren of the Acacus, may be taking their idolatrous ideas about these paintings, as with the shrines of Timbuktu in 2012, to a new level.

So far, there is no direct evidence of these paintings having come under such attack. But that is only because no one has been there to check. With the Acacus now occupied by many of the “terrorists” driven out of Mali, and liable to come under attack at any moment from French, Algerian and US Special Forces, we can only hold our breath as to what might be befalling this magnificent heritage, which, as local people appreciate, is an asset for their future financial security – but only if it is protected.

- Jeremy Keenan is a Professorial Research Associate at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies. He has written many books including The Dark Sahara (2009) and The Dying Sahara (2012). He acts as consultant on the Sahara and the Sahel to numerous international organisations, including the United Nations, the European Commission and many others.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo Credit: An image from the rock art sites of the Tadrart Acacus in Libya (Flickr/Roberto D'Angelo)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.