Trump will be president but U.S. foreign policy is governed by these rules

A new American president will take office next January. As he does so, he brings along with him approximately 4,000 senior officials, the most prominent of whom are his cabinet members, including the ministers in charge of defence, trade, finance, education, interior affairs and foreign relations. In addition, there is also the secretary of the National Security Council.

After the Second World War, the US became a national security state

All cabinet members need to be endorsed by Congress before they take office. The office of National Security Council (NSC) Secretary, like the offices of the president and the vice-president, exists within the White House itself.

For this reason, he needs no endorsement from Congress, despite the significant role he plays in determining, coordinating and implementing the president’s foreign policy and his important and strategic decisions.

This is actually what led to describing the post-Second World War state as the state of national security.

The council was set up in September 1947 by a decree from President Harry Truman. The council’s establishment signalled a radical change in the way the US saw itself and its role in the world.

Before assuming the presidency, Roosevelt noted the experience of President Wilson, who led his country into the First World War and tried, unsuccessfully, to impose a new world order on the main European imperialisms, then returned to Washington where he failed once more to convince the Americans of maintaining an active role on the world stage.

Roosevelt became convinced, especially after the US was caught in the flames of the Second World War – whether due to the German pressure exerted on Mexico to attack the US or the attack on Pearl Harbour - that the European war had become global in nature and that the US could not isolate itself from world crises, and that it had, if it wanted to maintain its security, to play a principal role in world affairs.

This is what led, eventually, to the founding of NSC and the other US security agencies, such as the CIA, whose mission was global in nature.

European war had become global in nature and the US could not isolate itself from world crises

At the same time, the Department of State was tasked with looking after foreign relations. The Department of Defence was given responsibilities that were not restricted to protecting America and its borders but also protecting whatever is considered to be American interests around the world.

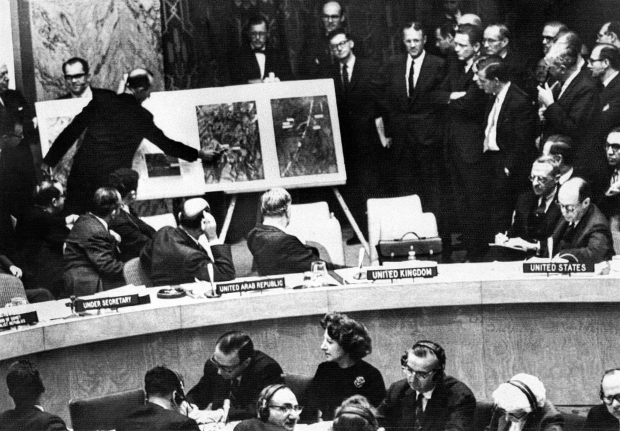

Even before achieving its decisive victory in the Second World War, the US embarked on building institutions that were international in nature, such as the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The United States assumed major roles in all of these with the aim of organising relations among the various countries.

The three frameworks

Yet three main strategic frameworks determine America’s foreign role, whether it be within international institutions or crises and conflicts raging beyond the borders of the United States.

There is also a continued discussion within decision-making circles and American strategic thinking about these frameworks, which are...

- how to determine the relationship of a certain crisis or region within the parameters of US national security

- the feasibility and effectiveness of direct or indirect intervention

- the necessity of preventing a single power from having sole control over any one geopolitical region in the world

There are regions in the world whose relationship with American national security can easily be determined. But there are other regions where such definition can be much more difficult and more complex.

During the early stages of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, there were few decision makers who could imagine a strategic American interest in intervening on the side of the Afghan resistance in an country that did not occupy a vital strategic location.

And despite the bloody massacres perpetrated by the Assad regime in Syria and the direct intervention of both Iran and Russia in the crisis, the Obama administration has remained adamant that Syria does not represent an issue of significance to American national security.

The burden of intervention

But on the other hand, the US has carried out dozens of military interventions since the Second World War.

The Korean War, the Vietnamese war and the wars waged by President George W Bush in the Middle East are the best known examples.

However, America’s strategic approach is divided, to a large extent, between those who advocate direct intervention and those who warn that such intervention is risky.

The failure of the wars waged by George W Bush in Afghanistan and Iraq... bolstered the view that advocates indirect intervention

In most cases intervention did not achieve its objectives: a more helpful policy would have been to work indirectly for changing the balance of power in conflict areas and to work with the concerned allies.

Different American administrations have always wavered between these two options.

READ: How Palestine links Donald Trump and Tony Soprano

Roosevelt himself worked initially along the lines of providing necessary support to the allies without burdening America with the costs of direct intervention.

He only decided to participate in the Second World War after Pearl Harbour. In contrast, Reagan invaded Grenada and sent American planes to bomb Libya. Yet in Afghanistan, he opted for an indirect and long-term role.

There is no doubt whatsoever that the failure of the wars waged by Bush in Afghanistan and Iraq – although both conflicts raged in the shadow of a quasi-global American monopoly, and without opposing interventions from other powers as happened in Korea and Vietnam – bolstered the view that advocates indirect intervention.

Bush’s wars inflicted severe damage on the image of the US, resulted in huge human and financial losses and ended with a withdrawal from the battlefield without accomplishing tangible objectives.

The American intervention in Libya in 2011 was limited and short term. It was undertaken with the aim of saving the face of the European allies when they proved incapable of continuing the war against the Gaddafi regime on their own.

The same applies to American interventions against Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, which have been extremely limited even if they have lasted long. In fact, it is local allies who bear the brunt of the war.

Weighing the options

The third strategic framework is linked to the ongoing debate about national security options and the nature of intervention.

Since the US took it upon itself to play a global role, Americans’ perception of their country is as a responsible power that is more than capable of managing global affairs and that is the natural Western inheritor of the modern world’s leadership grew manifold.

The Americans believe that it is necessary to prevent any other power from singularly seizing control of any of the world’s geopolitical zones

In order to maintain that role, Americans believe that it is necessary to prevent any other power from singularly seizing control of any of the world’s geopolitical zones, be they Latin America, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, East Asia and Southeast Asia.

The US waged a “cold” war for four decades in order to prevent the Soviets from imposing their hegemony over Europe.

Since Obama came to power, his administration has adopted a multi-faceted strategy and a multitude of tools in order to prevent China from extending its influence into the island chains of the Pacific.

On a smaller scale, there should be no doubt that the US does not want to see Turkish or Iranian regional hegemony, just as it strove before to deny Nasserist Egypt a leading role over its regional Arab neighbourhood.

READ: Why Trump should cooperate with Russia

American strategic debate often centres on how, with what tools and at what moment the US should intervene in order to confront or contain a certain power or prevent it from impose its hegemony over a given geopolitical zone.

The people selected by Trump for senior positions in his administration are attracting much interest.

Certainly, the background of these individuals is important when it comes to speculating about the policies of the new US administration. Backgrounds often play an important role in the process of selection.

Yet, what is certainly more important to understand the policies that the new administration is likely to adopt are the choices within those three strategic frameworks - the frames that determine US foreign policy.

- Basheer Nafi is a senior research fellow at Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: President-elect Donald Trump in West Allis, Wisconsin (AFP).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.