The Tunisia emergency: From Arab Spring ideal to military poster child

In a now-signature move, the government of Tunisia on 16 May again extended the state of emergency that has been in place since a series of deadly attacks carried out by Islamic State (IS) in 2015.

The Los Angeles Times explains that Tunisia’s emergency law “gives the government stepped-up powers to deal with suspected terrorists but also curtails to a degree the rights of ordinary citizens”, such as freedom of assembly.

In Tunisia and beyond, counter-terrorism has long been a convenient excuse for dismantling basic freedoms

For many Tunisians, the Times notes, the state of emergency “harks back to days when authorities acted with impunity to quell any dissent”.

In Tunisia and beyond, of course, counter-terrorism has long been a convenient excuse for dismantling basic freedoms.

Take the United States, for example, where the war on terror has done wonders in definitively obliterating all sorts of liberties - from privacy to freedom of the press to the right to exist as an Arab-American without being spied on by law enforcement and otherwise have one’s existence criminalised.

Meanwhile, the rights and privileges of the arms industry have only increased, as the US continues to wage both overt and covert war around the globe and to dutifully stock the arsenals of an array of unsavoury allies.

Economic insecurity becomes the norm

In the case of Tunisia, the US Defence Security Cooperation Agency reported in a May 2016 news release that the US state department had approved a sale to the Tunisian government of 24 Kiowa Warrior helicopters.

The news release put the estimated value of the transaction - including requested equipment, training, and support - at $100.8 million.

The items, the agency contended, would “improve Tunisia’s capability to conduct border security and combat operations against terrorists” and would “contribute to the foreign policy and national security objectives of the United States by helping to improve the security of Tunisia which has been, and continues to be an important force for political stability and economic progress in the North African region”.

But US foreign policy has also included not insignificant contributions to the rise of Islamic State and other militant outfits. It’s not entirely clear what US-directed militarisation will do for Tunisian security - or anyone else’s, for that matter.

Furthermore, there are presumably millions of better ways to achieve “economic progress” for the general Tunisian populace than via the acquisition of multi-million-dollar military goodies.

Indeed, economic insecurity happens to be a mainstay of existence in Tunisia, where the minimum wage is currently less than $140 per month and the social landscape is plagued by a dearth of services, including decent, affordable healthcare.

There are presumably millions of better ways to achieve “economic progress” for the general Tunisian populace than via the acquisition of multi-million-dollar military goodies

And while the US-backed mantra of Tunisian stability and progress has proved impressively resilient, the facts on the ground tell a different story.

In the southern province of Tataouine, residents have risen up against poverty and injustice in protests that recently turned deadly. There’s nothing like a handy state of emergency to justify brutal state repression.

Corinna Mullin, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Tunis, commented in an email to me on the “context of the current brave struggles in and in solidarity with Tataouine in the face of escalating state violence”.

She said that certain popular demands have “gained renewed currency” in Tunisia as a reaction to the neoliberal model aggressively marketed by international financial institutions, namely, “the nationalisation of the country's natural resources, redistribution of the country's wealth, sovereignty over questions of national interest and an end to the exploitation of foreign companies”.

An emergency in itself

For its part, a World Bank poverty assessment released in 2016 maintains that Tunisia is “the only success story of the Arab Spring revolution that swept the Arab world” in 2010-11 but that “substantive economic, political, social and security challenges remain, preventing demands by Tunisians on inclusive growth, good governance and sustainable development from truly materialising”.

If you’re wondering how exactly “success” fits into the picture, you’re not alone.

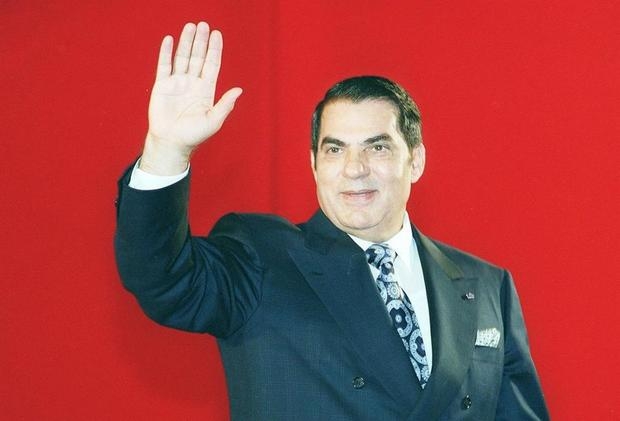

During my own recent visit to Tunisia, I heard various complaints that life is even more financially challenging now than it was during the dictatorship of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who was deposed in 2011.

As we explored olive orchards stretching as far as the eye could see, Ayeb referenced neoliberal efforts to forge a regional example out of Tunisia.

The reliance on export-led development had resulted in a situation in which, he lamented, olive oil is prohibitively expensive for many people - despite being a staple of the Tunisian diet and despite the obvious abundance of olive trees.

Surely, though, national shortcomings are nothing that can’t be hidden behind some determined strides on the security front.

When I travelled across Tunisia by car in early May, ubiquitous checkpoints gave the impression that the country was, in fact, the final and definitive front in an existential global war on terror.

At the small airport on the Tunisian island of Djerba, meanwhile, heavily armed, black-clad men in balaclavas caused me to momentarily think I had somehow stumbled onto the scene of the assassination of Osama bin Laden.

As the physical repression of Tunisian protesters continues to complement the economic injustice, so the never-ending state of emergency constitutes an emergency in itself.

- Belen Fernandez is the author of The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She is a contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Mourners gather in front of the house of a dead man hit by a police vehicle during protests over jobs, in Tatouine, Tunisia, on 23 May 2017 (Reuters)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.