Turkey at 100: Will Ankara move closer to Russia or the US?

As Turkey marks its centenary as a republic, it is important to explore the historical and contemporary factors shaping its future foreign policy - especially its mixed relationship with the West, which has been characterised by both tensions and mutual pragmatic interests.

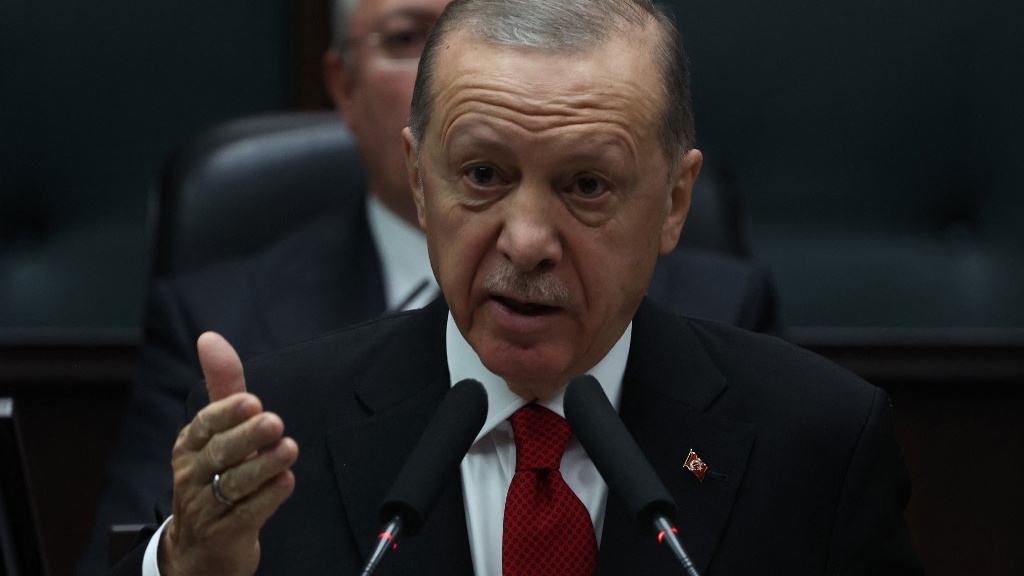

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent electoral victory has many implications for modern Turkey and its relationship with the West, especially the United States and the European Union. His new term could redefine these relationships and shape the country’s future trajectory.

Historically, there have been ups and downs in the popular and political receptions and perceptions of Turkey in the West, dating back to Ottoman times. As the Ottoman Empire consolidated power, it was looked upon with fear and bitterness in the West. These sentiments deteriorated further after the end of the First World War.

More recently, a series of events have complicated Turkey’s relationship with the West, especially the US. Turkey began to distance itself from the US when it refused the passage of American troops to Iraq in 2003. In 2011, it destroyed the US-Israel-Turkey axis by severing ties with Tel Aviv, and implemented a policy in Syria that ran counter to US interests. When the July 2016 coup was attempted, Turkey blamed the US.

Some of these factors have changed over time. For example, Turkey restored its strategic relationship with Israel due to mutual economic interests. It even welcomed Israel’s president to Ankara in March 2022, marking the highest-level meeting between the countries in 14 years. This was received favourably by western nations, especially the US.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But Turkey’s position on Syria, which aligns with the positions adopted by Russia and Iran, remains a point of contention and unease between Turkey and the West. Tensions between Turkey and Greece, both Nato members, also continue to strain Turkey’s relations with its western allies.

Turkey blames the US for hosting Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen, who has been living in self-exile in Pennsylvania since 1999. Turkey designated his global Hizmet movement as a terrorist organisation and blamed it for instigating the 2016 coup attempt. Repeated calls by Erdogan for the US to hand over Gulen never succeeded, further fuelling tensions.

Points of contention

More points of contention have emerged in recent years, including Turkey’s rapprochement with Russia. The pair have cooperated on oil and gas pipelines; Russia has sold weapons, such as the S-400 missile system, to Turkey, and provided technical assistance in the construction of Turkey’s nuclear plants; and the two nations have collaborated on trade.

Turkey is the only Nato member that didn’t support the imposition of sanctions against Russia over the Ukraine war. It even transported Russian fuel to China and Iran, bypassing the internationally imposed sanctions on Moscow.

Follow Middle East Eye's live coverage for the latest on the Israel-Palestine war

Turkey’s power stems in part from its role within Nato as a bridge between the East and the West, thanks to its unique geographic location, which spans Europe and Asia. Turkey played a key role in backing Finland’s bid to join Nato, and after initial opposition, it also accepted Sweden - a move rewarded by Washington’s approval of a deal for F-16 fighter jets.

Turkey’s attempt to link its approval of Sweden’s Nato membership to the approval of its own long-sought accession to the EU did not work out, creating another source of tension between Ankara and the West. But despite such tensions, Turkey’s fast-growing economy, rich natural resources, unique geographic location and strategic alliances explain why it remains important for both the West and its fiercest rivals, Russia and China.

Erdogan has distanced himself from being perceived as a puppet of the West, especially of the US, through building viable relationships with other strong countries

Turkey’s latest elections showed the faultiness of predictions about Erdogan’s dwindling power and sliding popularity. Hopes for an end to his rule turned out to be wishful thinking. Despite the small margin by which he won, he will continue to lead Turkey for a third term, earning the title of “Turkey’s strongman” for securing 25 years in power.

While Erdogan’s victory is very consequential for Turkey and its foreign policy, however, predictions are mixed when it comes to the country’s path forward vis-a-vis the West. Some expect Turkey to distance itself from the West and to lean more towards Russia, while others expect the opposite.

Those who adopt the first position argue that Turkey’s relations with the US and European countries will remain at best transactional, and vulnerable to circumstantial crises. Turkey is under US sanctions for purchasing the Russian S-400 system, Washington is concerned about Ankara’s deepening ties with Moscow, and US President Joe Biden has kept Erdogan at arm’s length due to a decline in democratic standards.

Turkey, in turn, is outraged over US support for armed fighters in Syria affiliated with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), and it is wary of deepening political and defence cooperation between its arch-rival Greece and the US.

Maneuvering power

Those who adopt the second position, meanwhile, cite Russia’s increased international isolation and diminished military reputation as a result of the attempted mutiny by the Wagner Group and the prolonged war in Ukraine.

These perceived weaknesses on Russia’s part could strengthen Turkey’s maneuvering power as the only Nato country that didn’t back sanctions on Russia. They also stress the importance of Turkey’s continued relationship with the US and its western allies.

Between these two contradictory positions, there is a balanced middle ground that acknowledges the challenges in Turkey’s relationships with its western allies, while also stressing the value of successful engagement to overcome these challenges. While acknowledging that Turkey will be a thorn in the West’s side for years to come, this position also takes into account Turkey’s G20-sized economy, diplomatic expertise, military strength and location, which make it absolutely essential to the West.

Those who adopt this middle position argue that through direct engagement between the leaders of Turkey and its western allies, especially the US, important wins have been achieved, including Nato accession for Sweden, F-16 sales, a ceasefire with the PKK (or at least continued Turkish restraint in northeastern Syria), calm with the Greeks, and progress on Armenian-Azeri rapprochement.

This position maintains that a smart revival in Turkey’s relationship with the West is not just essential; it is the only way to achieve both parties’ goals and to serve their mutual interests. It may also be the best way to pragmatically contain what has been described by some critics as the “storm of Erdoganism”.

Building ties

Erdogan has distanced himself from being perceived as a puppet of the West, especially of the US, through building viable relationships with other strong countries, including Russia and China. He has also gotten closer to Iran in recent years. This policy is based on the necessity of solidifying and diversifying Turkey’s strategic partnerships and alliances to safeguard its interests in the political, economic and military spheres.

Significantly, Erdogan has successfully remained relevant in the global arena by keeping Russia close and stressing his commitment to Nato, while extracting maximum concessions from both sides - a delicate balancing act. Although some of his recent tactics, especially his position on Sweden’s Nato membership, have angered Russia, it is unlikely that such moves would erode the foundations of their transactional relationship.

In a multipolar world, the winners will be those who can navigate these new realities and negotiate with more than one strategic power

Likewise, it is unlikely that Turkey’s policy on Syria and its increasing closeness with Russia, China and Iran would erode Turkey’s transactional relationship with the West.

Moving forward, Turkey can choose between three scenarios: favouring its western allies at the expense of its relations with Russia and China; favouring the latter at the expense of the former; or continuing to skillfully balance these relationships. The third scenario seems more realistic. In a multipolar world, the winners will be those who can navigate these new realities and negotiate with more than one strategic power to safeguard their interests.

Turkey has been successfully doing just that through its balanced transactional relationships with the East and the West, and it will most likely continue on the same path during Erdogan’s third term and in the post-Erdogan era.

Another balancing act that is equally vital for Turkey’s future foreign relations is its ability to keep its position of regional influence in the Middle East, while maintaining its geostrategic relationship with Israel. This seems to be more challenging than ever in the midst of the Gaza crisis which started unfolding on 7 October 2023.

Turkey has been criticised for taking a primarily rhetorical position on this grave humanitarian tragedy which condemned Israel’s attacks on innocent civilians in Gaza and criticised the West for backing Israel, without taking more decisive practical steps, such as cutting diplomatic ties with Israel, for example, or even threatening to do so.

Turkey’s ability to skilfully walk these tight ropes and juggle these diplomatic balls will determine its success or failure as a regional and international power to be reckoned with.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.