Northern Syria has become Erdogan's punchbag

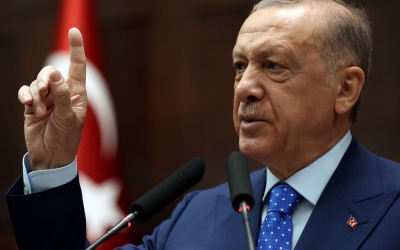

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has announced that Turkey will soon be moving into northern Syria to clear Tel Rifat and Manbij of Kurdish “terrorists”. This will be Ankara’s fourth military incursion into the region in six years. As before, Erdogan will seek to expel the Kurdish militias currently controlling these areas and replace them with pro-Turkish Syrian rebel forces, turning the towns into client regimes along the Turkish border.

Ankara has been unhappy about the presence of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the Syrian affiliate of the Turkish separatist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), along its border ever since they moved in during the Syrian war. But the Syrian Kurds have only rarely used their position to launch attacks on Turkey, and there has been no significant increase in terror strikes that might necessitate this sudden incursion.

Such attacks to boost Erdogan's domestic popularity at an opportune moment internationally are becoming a predictable pattern

In reality, Erdogan’s actions are led not by developments in Syria, but by his own domestic concerns and the opportunities provided by the current geopolitical climate.

Domestically, after two decades in power, Erdogan’s popularity is flagging, and he and his party are under serious threat of losing both the presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023. The economy is struggling, while hostility is growing towards the 3.6 million Syrian refugees who Erdogan personally welcomed. The president hopes a move against the YPG in northern Syria could relieve some of this domestic pressure.

Anti-YPG/PKK operations are generally well-received, especially among the nationalists who Erdogan wants to win back. In the past, conquered parts of Syria have also been identified as possible “safe zones” to repatriate unwanted refugees. While in reality very few have been sent back to these captured areas, the idea plays well with voters.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Moscow and Washington

Yet, equally important is the changing international situation that is facilitating Erdogan’s move. While Turkey is an important external player in the Syria conflict, it is subordinate to both Russia and the US, who control the airspace. Past Turkish invasions and operations against the YPG have been possible only with the approval of either Moscow or Washington. Yet, both have opposed further attacks for different reasons and certainly won’t endorse Erdogan’s 2019 plan to build a huge 30km buffer zone along the Turkish-Syrian border.

But at the same time, neither are expected to raise serious objections to the capture of Tel Rifat and Manbij.

What has changed? In a word: Ukraine. Russia is distracted by the gruelling conflict and is removing some forces from Syria, so it can’t seriously resist Turkey’s operation, despite having agreed with the Syrian Kurds to keep Turkey out of Manbij in 2019.

Though Russian President Vladimir Putin will not welcome Erdogan exposing Russia’s weakness in this way, he also needs Turkey to maintain its guarded stance on Ukraine, and will possibly be willing to sacrifice Moscow’s agreement with the Syrian Kurds. Moscow would also rather Turkey carve off Kurdish territory than reignite conflict in the more valuable Idlib area, which it and the allied Assad regime are not in a strong position to defend.

The US is in a more difficult position, given it is allied with the YPG via its leading role in the Syrian Democratic Forces coalition that Washington sponsored to defeat the Islamic State (IS), much to Ankara’s outrage. The last time Erdogan attacked, in 2019, US public opinion was furious at the Trump White House’s abandonment of its ally, forcing then-President Donald Trump to broker a Turkey-YPG ceasefire.

But US priorities have changed, and Erdogan knows this. It, too, wants to maintain Ankara’s relative neutrality on Ukraine and certainly doesn’t want Turkey to get any closer to Russia. Moreover, Washington wants Erdogan to drop his opposition to Sweden and Finland joining Nato, based on their refusal to extradite exiled PKK members to Turkey and their objections to Ankara’s 2019 attack.

Demanding a higher price

Erdogan knows he is in a strong position, and he may ultimately demand an even higher price from Washington for accepting these new members, such as being restored to the F-35 fighter jet programme.

He would certainly expect the White House to turn a blind eye to his capture of these Kurdish pockets, which would still leave the majority of the YPG’s territory under US protection intact.

Such attacks to boost Erdogan’s domestic popularity at an opportune moment internationally are becoming a predictable pattern. His previous invasions came at similar moments.

In 2019, Turkey launched Operation Peace Spring a few months after Erdogan’s AK Party had lost key local elections in Istanbul and Ankara when anti-refugee sentiment was rising. The operation boosted the president’s popularity and created a space for Syrian refugees to be moved into, although nowhere near the intended two million. Crucially, it was facilitated by Washington, with Trump surprisingly withdrawing some US forces, giving Erdogan an advantage.

Before that, Operation Olive Branch in early 2018 saw Turkey attack the Kurdish town of Afrin, again at a time of domestic uncertainty for Erdogan. Such was the connection to domestic politics that the AK Party, after receiving a poll boost following the invasion, brought forward elections to June 2018, stating that “developments in Syria and elsewhere have made it urgent”.

Again, the attack was facilitated by external players, this time Russia. Putin agreed to allow Turkey into Syrian airspace, in exchange for Turkish silence when Moscow aided Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s conquest of parts of Idlib, Damascus, and the south later in the year.

This same pattern was the case in 2016 when Turkey launched Euphrates Shield, an operation against IS that also aimed to cut off the advancing Kurds. Again, this was led by domestic and international politics. Domestically, Erdogan was flexing his muscles after facing down an attempted military coup a few months prior, while internationally, it was agreed with Russia, which accepted Turkey taking territory in the north if it cut support for rebels in Aleppo, allowing Assad to capture the city.

In short, Turkey’s invasions have had little to do with events on the ground in Syria and, despite the rhetoric from Erdogan, are not driven by any newly emerging security concerns. Instead, these Kurdish-controlled regions of northern Syria are becoming Erdogan’s punchbag: areas he can hit when it suits his domestic agenda, provided the international circumstances allow him. This situation looks unlikely to change while the Turkish president remains in power, and with lots of areas along the Syrian border still under YPG control, future incursions seem likely.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.