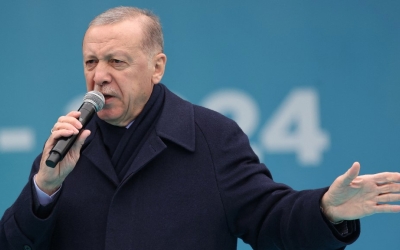

Turkey-Syria relations: Will Erdogan and Assad reconcile?

When Recep Tayyip Erdogan recently extended an invitation to Syrian President Bashar al-Assad for a meeting, the Turkish president was signalling his openness to dialogue.

Erdogan’s agenda appears to be driven primarily by domestic considerations, aiming to challenge his opposition - which has also called for its own meeting in Damascus - by taking bold steps towards the Syrian regime, including working towards the safe and voluntary return of Syrian refugees.

This strategy aligns with Erdogan’s broader approach of maintaining good relations with Turkey’s neighbours in the region. Ankara’s main concerns are Syrian refugees and combatting threats from the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

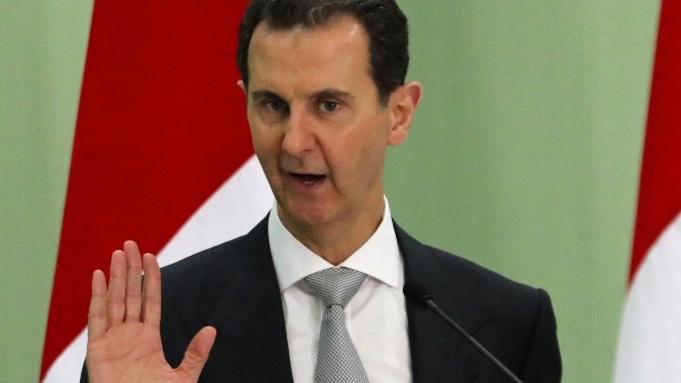

Assad, under pressure from Russia and seeking to demonstrate victory to his loyalists, has welcomed the Turkish initiative, although it remains unclear whether, or when, such a meeting may actually happen.

But Assad has also highlighted the lack of progress in previous security-level meetings, reflecting the need to balance Iranian demands for a full Turkish withdrawal from Syria against Russian efforts to alter Syrian dynamics and weaken Iranian influence.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Assad’s primary objectives for any forthcoming meeting include the withdrawal of Turkish forces from Syria, and the cessation of Turkish support for Syrian opposition factions.

These demands align with Iranian interests, as Assad recognises he cannot confront the SDF while the group is under US protection.

Crucial symbolism

The symbolism of the two leaders shaking hands would be crucial for both, albeit for different reasons.

Turkey remains steadfast in its stance, refusing to withdraw its forces until the PKK threat is eliminated and Syrian refugees have safely returned home. Turkish officials have suggested that Ankara will continue to support Syrian opposition groups, which complicates negotiation dynamics, as Damascus views Turkish disengagement as a prerequisite for any meaningful dialogue.

Today, Russia and Iran hold the upper hand in Syria after the decimation of the Syrian army in the conflict. This shift has created new centres of power in the country, reflecting a new balance on the ground.

Erdogan, Assad and neighbouring states remain eager for a photo-op of the two leaders together, as a means to further their own agendas

While Assad makes final decisions as president, his primary concern remains holding onto power, regardless of the cost. His decisions are heavily influenced by Russia and Iran, and he tries to balance them in a way that keeps him in power. But the country’s intelligence service, aligned with Tehran, has reportedly obstructed the Russia-facilitated Turkey-Syria rapprochement process.

According to an Iraqi official who spoke to Middle East Eye on condition of anonymity, Syria’s intelligence agency has “delayed responses to proposals” and insisted on “a clear timetable for Turkish withdrawal from Syria before engaging in any security and intelligence cooperation”.

“While appearing constructive, these proposals align with Iran’s interests and are likely unacceptable to Turkey,” the official said. “They include a temporary presence of Turkish forces in Syria for up to three years in exchange for a clear withdrawal timetable. Initial meetings would discuss reopening embassies and reactivating diplomatic relations, requiring Ankara’s approval to dismantle the civil administration system in areas under its control.”

The Syrian government would then assume duties in these areas, with counterterrorism consultations paused until significant progress is made, the official said.

Iran exerting pressure

The Syrian defence ministry - with which Russia is working to rebuild the Syrian army as a professional force and restructure it to reflect post-crisis Syria - is more open to Russian-mediated cooperation with Turkey.

The ministry has proposed joint cooperation in the eastern Euphrates region, which would be conditional on Turkey dismantling moderate armed opposition factions and integrating them into the Syrian army.

Meanwhile, according to a source at the Syrian foreign ministry, the Iranian embassy in Damascus continues to exert pressure on the Syrian government to ensure a swift withdrawal of Turkish forces from the country, while also pushing for increased security and intelligence coordination to dismantle terrorist groups.

In addition, Iran has been opening new lines of credit to the Syrian regime in hopes of exerting greater control over the Syrian economy.

Conversely, the Russian embassy in Damascus, according to the Syrian foreign ministry source, has been pressuring Assad to achieve tangible progress in negotiations with Ankara.

Russia ultimately wants the US out of Syria, hoping that Syrian, Russian and Turkish forces can fill the power vacuum instead of Iran and its militias, thus enabling Russia to control much of Syria’s natural wealth.

Last month, reports emerged that Iraq’s government wanted to host an initial meeting between Erdogan and Assad. Damascus appears keen to leverage the Iraqi initiative to gain time, without committing to any substantial steps.

Meanwhile, the fundamental differences in the objectives of Syria and Turkey, coupled with the external influences of Iran and Russia, create a complex landscape for achieving any comprehensive settlement between the two nations.

But Erdogan, Assad and neighbouring states remain eager for a photo-op of the two leaders together, seeing it as a means to further their own agendas.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.