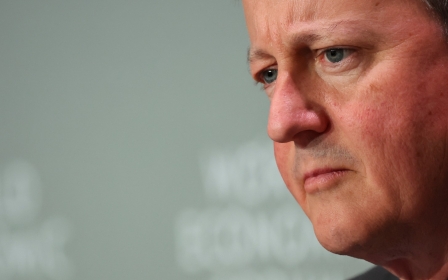

War on Gaza: Why is David Cameron silent on Israel's invasion of Rafah?

For three months, the British government has repeatedly voiced concerns regarding the Israeli intention to launch a ground invasion of Rafah.

Yet, when the actual Israeli invasion kicked off this week, the British government was deathly silent.

No ministerial statement, no government press release and no social media posts. David Cameron, the UK foreign secretary, has embarked on an impressive disappearing act.

When he did finally pop up to make a major foreign affairs speech on Thursday, he made three standard references to Gaza and not one about any invasion of Rafah. He dodged the chance to stand tall on the world stage.

Government ministers would score a set of perfect 10s for the verbal gymnastics in order to skip past the understandable parliamentary and media questions fired off at them.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak deployed that favourite line that he is "deeply concerned" about a full military incursion of Rafah. Sunak was also deeply concerned back in mid-February. It was as if the tape was on a constant loop.

One might have expected a British government statement pushing all sides to step back from the brink and push for a pause in the fighting, leading to a credible ceasefire. This has been the preferred British formulation for months.

Lame moves

The government did not even provide a ministerial statement to Parliament. It was left to the shadow foreign secretary, David Lammy, to seek an urgent question which the speaker granted.

Follow Middle East Eye's live coverage of the Israel-Palestine war

The deputy foreign secretary, Andrew Mitchell, was forced to answer in the Commons, but sounded no more concerned that he did a week ago. He acted as if the situation had not altered one jot. "There is no difference between what I have said today and the response I gave on the last occasion I was at the dispatch box."

Mitchell’s floor routine was convoluted, involving an impressive backflip.

On 30 April Mitchell stated: "Given the number of civilians sheltering in Rafah, it is not easy to see how such an offensive could be compliant with international humanitarian law.”

It is a cardinal principle of this Conservative government not to make any determination that Israel’s actions in Gaza might have broken international humanitarian law

By 7 May, Mitchell commented: “We have not seen a credible plan for military action in Rafah so far, so we are not able to judge whether it would be in accordance with international humanitarian law.”

The "logic" of this position is that Israel was wise not to share its plans for a Rafah invasion with the UK government.

Sunak, Cameron and Mitchell are clearly grateful for having been saved the trouble of having to determine whether any plan was legal or not. Mitchell did not call for Israel to share any such plan. That might be awkward. Mitchell would not be drawn, of course, as to whether Israel’s actions as opposed to plans were legal or not.

It is a cardinal principle of this Conservative government not to make any determination that Israel’s actions in Gaza might have broken international humanitarian law.

The government just calls on Israel to adhere to international law but never opines as to whether it has been breached. Such timidity was never displayed in the case of Russia in Ukraine, or with Syrian regime actions against its own people.

The government has several standard lame moves. The first one is to call upon Israel to investigate a situation, treating Israel as if it was a credible partner perfectly able and willing to do so despite all the evidence to the contrary.

The second ruse is to say that it is not for the UK government, let alone the opposition, to determine whether Israel has broken international law. It has to be an independent judicial body.

Until last November the British government did not even accept the International Criminal Court (ICC) had jurisdiction in Palestine. As for the International Court of Justice (ICJ), its initial response was not to insist that Israel had to abide by the provisional measures the ICJ ordered back in January.

As for the ICC, government ministers have again reverted to trappist mode over the threats from 12 US Republican Senators against Karim Khan, the ICC's chief prosecutor. Khan is a British citizen threatened by powerful American politicians merely for the possibility he might dare to do his job. It is reminiscent of the Sopranos.

Cameron had also sounded highly concerned about the freedom of press. That was on the World Press Freedom Day on 3 May. "The UK will always champion a free press," he tweeted.

This was a policy position that lasted all of three days because by 6 May, he had nothing to say about Israel banning Al Jazeera.

A political heavyweight?

Where does this leave Cameron? Since becoming foreign secretary in November, he has sounded for much of the last six months a little bit more deeply concerned than his boss. In February, he said that the conflict in Gaza had to stop "right now".

Many Conservatives touted Cameron's appointment as foreign secretary as the insertion of a political heavyweight into the diplomatic arena. They pointed out that, as a former British prime minister, he could gain access more easily than lesser-known foreign secretaries.

In reviewing the leaderships of the Middle East, Cameron would have seen many familiar faces – Netanyahu in Israel, Sisi in Egypt, King Abdallah in Jordan, as well as Mohammad bin Salman in Saudi Arabia.

Another advantage Cameron has over his predecessors is that he is now Lord Cameron of Chipping Norton. Foreign secretaries in the House of Commons can barely leave London for more than a few days a week, before having to return for debates, votes and constituency commitments. As a Lord, Cameron has been able to rack up considerable airmiles, including around the Middle East. In total, he has visited 33 countries.

So why is Cameron silent now on Rafah? Sources inside the British government indicate Cameron has been “sat on". Whereas a few months ago, he was largely in charge of shaping the British position, Downing Street, it seems, has clipped his wings.

He may have to stick to a pro-forma script that maintain Britain’s complicity in the ongoing Israeli crimes but without any of the diplomatic oomph that Cameron did for a while inject into a flagging diplomatic scene.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.