UK government's undermining of EHRC is a threat to democracy

This week's report by the parliamentary human rights committee on Black people, racism and human rights makes for sobering and shocking reading.

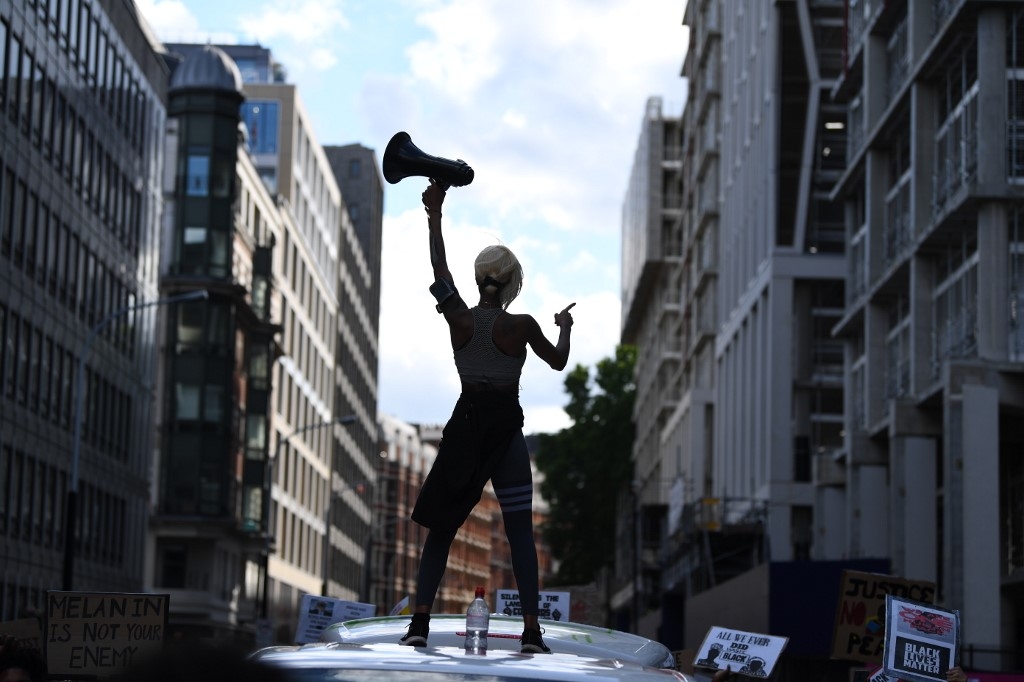

It was written in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May of this year and the global impact of the Black Lives Matter movement. It details systematic racial inequality in the UK and deep concern by Black British citizens about fair and just treatment.

What is perhaps most shocking, however, is its scathing criticism of the body charged with ensuring the address of racial injustice, the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC).

The EHRC is the successor body to the Commission on Racial Equality, which had been set up in the 1970s. It was given extra impetus in the aftermath of the murder of Stephen Lawrence and the Macpherson Inquiry’s finding in the late 1990s of institutional racism in the Metropolitan Police.

Since then it has taken on responsibility for the extended range of protected characteristics set out in the Equality Act 2010. But it has also had its budget cut and become increasingly subject to government control. It no longer seems to treat the disadvantages experienced by Britain’s ethnic minorities as a priority.

It failed to act over the government’s “hostile environment” policy for immigrants, despite the evident signs of its serious consequences for citizens who came to Britain from the Caribbean and the wider Commonwealth. Belatedly, the EHRC in June launched an assessment of the consequences of the policy.

It has also failed to act on the consequences of the Prevent strategy for British Muslim citizens. Its own reports to the UN – necessary for it to maintain its accreditation – indicated very serious concerns. But it took no action domestically.

Until the appointment this week on a year-term of Lord Ribeiro, a Conservative member of the House of Lords, there were no Black commissioners.

This was something the outgoing EHRC chair, David Isaac, drew attention to when leaving his post. The commission had made nominations, he said, but they had not been adopted by the government. The government prefers to appoint from the business sector, rather than those active in civil society addressing inequalities.

Its appointments have also included those who are actively hostile to the idea of systematic racism or Islamophobia. The appointment of David Goodhart, which the government announced on the same day that the human rights committee report was released, is emblematic, but it follows a trend.

The first chairman of the EHRC, Trevor Phillips, cast doubt on the idea of Islamophobia and also on the idea of institutional racism. He has since gone on to play an influential role at the right-wing Policy Exchange think tank where he is joined by Goodhart.

Multiculturalism is central to the remit of the EHRC, but Phillips and Goodhart see it as the cause of segregation. They fail to see that segregation is a product of the poverty and disadvantage disproportionately experienced by Britain’s ethnic minorities. In fact, the EHRC itself increasingly sees its remit to be individual discrimination, not structural inequality.

Its most recent report on the gender pay gap at the BBC finds no evidence of pay discrimination. This has raised the ire of women’s groups, both for its cursory treatment of the issue and the specific finding.

This provides the clue to the EHRC’s agenda. It no longer countenances the idea of institutional inequality. It treats all inequalities equally – none of them are systematic, and none of them follow from government policy. It has shifted from being an independent body that should hold public bodies to account to being an agent of government policy.

British institutions and legal frameworks are to be endorsed and not subject to criticism, except under fear of sanction. This is according to the government’s recently published guidelines for schools about the use of external agencies providing curriculum material. Claims of systematic inequality are potentially an indication of non-violent extremism and subject to the strictures of Prevent.

Yet, the government actively subverts democratic scrutiny by undermining independent bodies like the EHRC through a politicised appointments process. It has recently been leaked that it favours the appointment William Shawcross – linked to the neoconservative think tank, the Henry Jackson Society – to be the independent reviewer of Prevent.

This is taken from the Trumpian playbook. It represents a threat to democracy that is more insidious than the purported "extremism" with which the government professes concern. It is a threat that lies at the heart of government itself.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.