Tony Blair can never escape his role in the Iraq disaster

A distinguished film producer of my acquaintance once recounted to me an exchange he had with one of Tony Blair’s closest advisers in December 2000. The official had just flown back from Washington, where he had been meeting the transition team of incoming US President George Bush. According to my friend, almost his first words were: “They’re fucking lunatics. Who knows what they’ll get us into?’

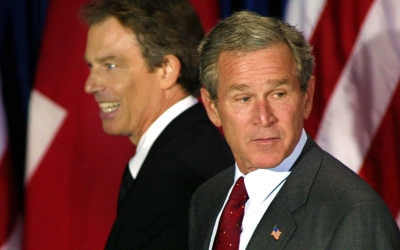

What they got us into, of course, was an interminable war in Iraq - a vast, toxic quagmire. Blair, the former British prime minister who more than anyone else was responsible for persuading the British parliament and a majority of the public that British soldiers should take part in the invasion of Iraq, remains in denial. Almost alone, he insists to this day that it was the right decision - but one has only to look into his eyes, whenever he is challenged on the subject, to see that he is haunted by it. Iraq never goes away.

The Americans were keen for British participation, not because they needed the military muscle, but because they needed diplomatic cover

Twenty years on, the subject is back in the headlines following a decision by the Queen to make Blair a Knight of the Garter, one of the UK’s highest honours, awarded solely at the discretion of the monarch. Ordinarily, such an award to a former prime minister, particularly one who held office for a decade, would be uncontroversial. Sooner or later, most former prime ministers are so honoured, and no one raises an eyebrow.

This time, however, it is different. No sooner had the announcement been made than Blair’s many enemies launched an online petition requesting that the Queen reconsider. At the time of writing, it had attracted more than a million signatures. Overwhelmingly, the signatories are likely to be those who opposed the war from the outset - many of whom regard Blair as the devil incarnate - but the right-wing media, who at the time were by and large in favour of the war, are also stirring the pot.

In particular, they have alighted upon a recent memoir by Blair’s former defence secretary, Geoff Hoon (See How They Run), who alleges that he was ordered by an official in Blair’s office to burn a memorandum from the attorney general, which implied that without specific UN endorsement, the war was illegal.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The official concerned - who incidentally is the very one quoted by my film producer friend - denies ever having given such an order. All the same, Hoon’s allegation has a plausible ring to it. Everyone knows that the former attorney general, Peter Goldsmith, struggled to find a legal justification for the war.

Position threatened

The bigger picture is this: from the moment Bush became president, Iraq was always going to be invaded. The only decision for the UK, the closest ally to the US, was whether or not we would participate. And even had we chosen not to, British troops would have ended up in Iraq anyway, because after the invasion we, like other major powers, would have felt obliged to go in and - with the backing of the UN - help clear up.

It is also true, however, that like France and Germany, the UK could have opted out of the war. Bush gave Blair that option when it became apparent that Blair’s own position was threatened. As Bush remarked at the time, he was seeking regime change in Baghdad, not London.

The Americans were keen for British participation, not because they needed the military muscle, but because they needed diplomatic cover. They wanted to be able to argue that they had wider international support. Blair was anxious to get involved partly because, like all British prime ministers, he believed that it was in Britain’s strategic interests to keep in line with the Americans.

Also, one suspects, it was because it gave him a role on the global stage that he would not otherwise have had, though at times it looked a little humiliating. One US newspaper dubbed him “America’s newest ambassador”.

In fairness, and contrary to what is sometimes asserted, Blair was not without influence in Washington. It was he who, together with the then-US Secretary of State Colin Powell, persuaded Bush to overrule then-Vice President Dick Cheney and take the issue to the UN Security Council, in hopes of a resolution explicitly authorising an invasion in the event of Saddam Hussein’s non-cooperation with weapons inspectors.

For Bush and the small coterie of his father’s friends who surrounded him, however, Iraq was unfinished business. Cheney and then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld were veterans of George Bush Senior’s administration. They regretted not overthrowing Saddam’s regime when they had the chance, following Saddam’s eviction from Kuwait in 1991. They were the key decision-makers in Washington, and they were not going to be deflected.

'I was incredulous'

In his memoir Against All Enemies, a former US national security adviser, Richard A Clarke, describes the difficulty he and his colleagues had in persuading Bush to take seriously the threat posed by al-Qaeda. He then describes what happened when he went into the White House the day after 9/11.

At times, it was my impression that Blair was hoping that Saddam would back down, depriving the Americans of an excuse to invade. As the deadline approached, however, that hope faded

“I expected to go back to a round of meetings examining what the next attacks could be, what our vulnerabilities were, what we could do about them in the short term,” Clarke writes. “Instead, I walked into a series of discussions about Iraq. At first I was incredulous that we were talking about something other than getting al- Qaeda. Then I realized with almost a sharp physical pain that Rumsfeld and [his deputy Paul] Wolfowitz were going to try to take advantage of this national tragedy to promote their agenda about Iraq.”

Later that day, he and some colleagues came across Bush alone in the Situation Room. “He grabbed a few of us and closed the door… ‘Look,’ he told us, ‘I know you have a lot to do and all… but I want you, as soon as you can, to go back over everything, everything. See if Saddam did this. See if he’s linked in any way…’ I was once again taken aback… ‘But, Mr President, al Qaeda did this.’” According to Clarke’s account, Bush replied: “I know, I know, but… see if Saddam was involved. Just look.”

There was, of course, no evidence that Saddam had anything to do with 9/11, so another reason was required: evidence that he possessed chemical and biological weapons, in breach of various UN resolutions. This was an easier furrow to plough. There was no doubt that Saddam had possessed such weapons. Indeed, he had used them against both his own people and the Iranians. What’s more, he had unsuccessfully attempted to acquire the technology to make nuclear weapons.

In addition, there were Iraqi exiles who claimed to have sources inside the regime willing to confirm that Iraq was still in possession of chemical and biological weapons. Even Hans Blix, the UN weapons inspector, did not say there were no such weapons - only that he wanted more time. The fact that the Iraqis were clearly failing to fully cooperate with UN weapons inspectors only added to the suspicion that they had something to hide.

Ringside seat

Throughout the long lead-up to the invasion, I had a ringside seat. I was a member of the parliamentary liaison committee, an obscure body consisting of half a dozen backbench MPs that met regularly with senior members of government, including the prime minister. One of our functions was to convey to the government the deep scepticism of Labour backbenchers about the justification for the war.

At the time, it was my impression that Blair was hoping that, finding himself confronted by overwhelming odds, Saddam would back down, depriving the Americans of an excuse to invade. As the deadline approached, however, that hope faded.

My view, for what it is worth, was that whether or not Saddam possessed weapons of mass destruction, there were no grounds for an invasion. I wavered until the last moment. I admired Blair. I wanted him to be right, but in the end I was one of the 139 Labour MPs who voted against British participation in the invasion.

By any standards, it was a huge misjudgement. Blair himself has spoken of his 'colossal isolation'

Ultimately, of course, it turned out that Saddam’s chemical and biological weapons had long ago been destroyed. The obvious question arises: why, if he no longer possessed any such weapons, had he not come clean to UN inspectors? The answer did not emerge until years later, when Saddam was captured and interrogated. He was more afraid of the Iranians than he was of the Americans. Big mistake.

Many of Blair’s enemies believe that he lied. I do not believe he did, although he did sail close to the wind at times. So far as the British were concerned, Iraq was at heart an intelligence screw-up. Throughout the build-up to the war, our foreign intelligence service, MI6, was telling the government that Saddam did possess weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Hoon confirmed that in the months before the invasion, he was shown “consistent and detailed intelligence” that Saddam possessed such weapons.

Long after Iraq had been invaded and occupied, MI6 remained convinced that WMD would be found. How do I know? In October 2003, by which time I was a Foreign Office minister, I was told by a deputy head of MI6 that they were sure Saddam’s chemical and biological weapons would soon be found, “once the Iraqi scientists start talking”.

I later quoted this to a well-connected friend in Washington. He laughed and said: “The Iraqi scientists are talking, and they are saying the same now as they were when Saddam was in power.” Namely, that Saddam had disposed of his remaining chemical and biological weapons at least seven years earlier.

Tragic consequences

Later, a senior civil servant, by now retired, told me that months after the war began, he had been present at a high-level meeting during which a senior member of MI6 suddenly inquired: “Would it be a problem if there turned out to be no WMD?” My informant said: “The silence around the room was palpable.”

The consequences of the Iraq war are well known. Even by the terms of reference of those who planned the war, it was surely a catastrophe. Al-Qaeda, which wasn’t present before the invasion, became rampant. Iran’s influence was much increased; that surely wasn’t part of the plan. And then there are the human costs, about which Blair has expressed much anguish: hundreds of thousands dead and maimed, millions displaced, a succession of barely functional governments - to say nothing of the damage to relations with the UK’s allies around the world.

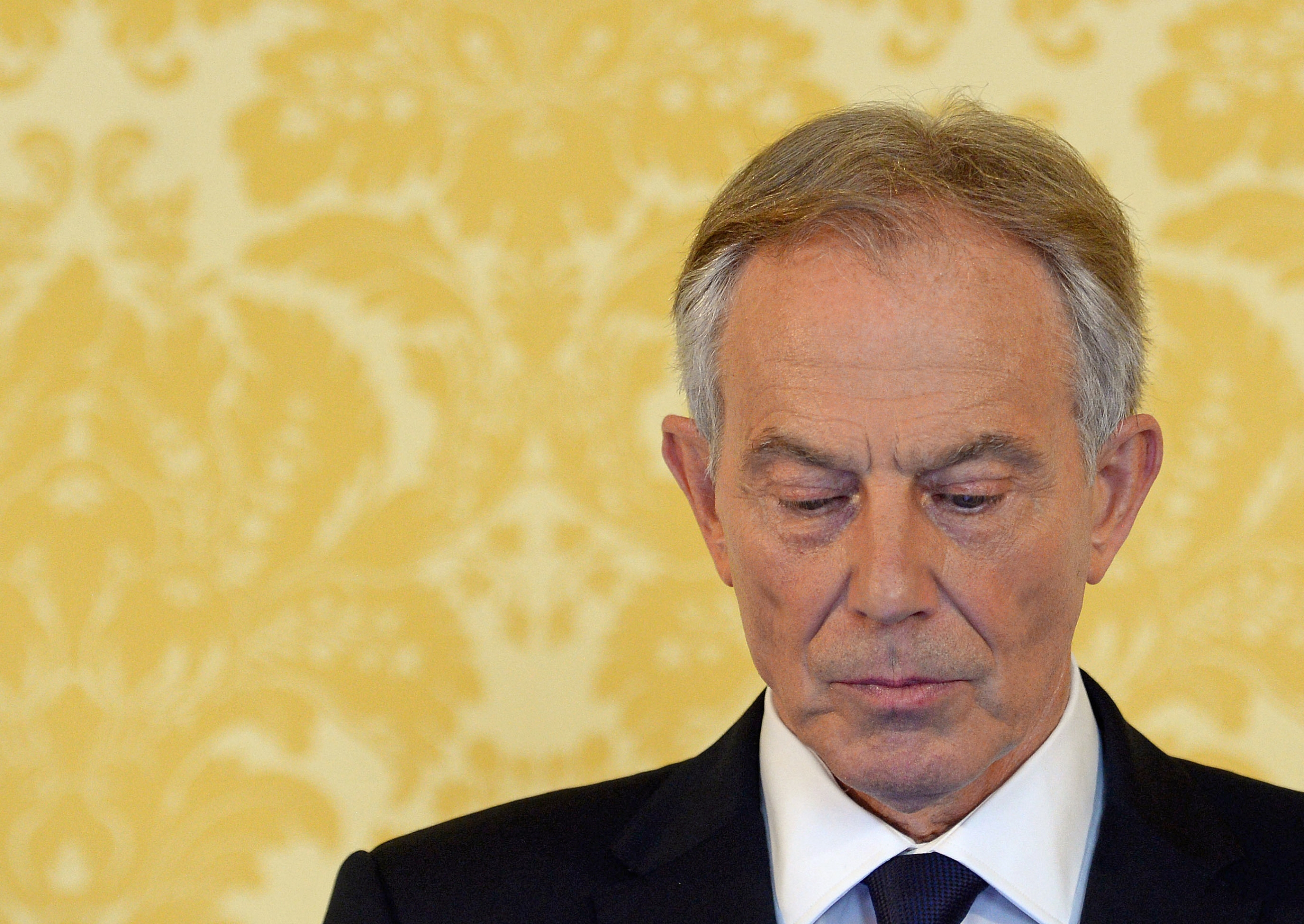

By any standards, it was a huge misjudgement. Blair himself has spoken of his “colossal isolation”. In personal terms, although this pales in comparison to the wider consequences, it is a tragedy. He was one of the outstanding political leaders of my lifetime: charismatic, stunningly articulate, personally likeable.

His government had many achievements to its name, not least peace in Ireland, which had eluded all British prime ministers for decades. He played a leading role in putting an end to ethnic cleansing in the Balkans. At home, the lives of many of my poorest constituents were transformed on his watch. But for Iraq, he would be seen as one of the outstanding British leaders of the postwar era.

I once asked Hoon where it all went wrong. He replied: “Blair had excellent relations with Bush. Jack Straw [the former foreign secretary] had excellent relations with his opposite numbers, Colin Powell and Condi Rice. But none of us had a line to Dick Cheney. And we didn’t realise, until too late, that Cheney was the president.”

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.