US foreign policy: The four moves that could save Washington

To maintain the United States' leadership of the so-called “rules-based world order”, President Joe Biden's administration is attempting to square a circle in a complex geopolitical quandary. In order to successfully achieve this, Washington would have to complete four ambitious moves.

The first one, the defeat of Russia following the golden opportunity President Vladimir Putin offered with his ill-conceived and badly executed invasion of Ukraine, has been ongoing for more than 18 months.

The second is to contain China politically, economically and technologically to prevent it from becoming the 21st century’s dominant power. This requires the rallying of the US’s European and Asian allies and partners at any cost, through a re-issuing of the “either you are with us or against us” edict.

The third move is the rescuing of what remains of Pax Americana in the Middle East. This entails keeping China away from the region, further isolating Iran, and luring in Saudi Arabia via a complex trilateral arrangement with Israel, without demanding from the latter any significant concessions on the Palestinian issue.

The fourth is preventing the birth of a different multipolar order through an intensive courting of India, which is mainly aimed at disarticulating the Brics group (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

This article deals with the first three moves. As for India, it is better to await the outcome of the Brics summit taking place in South Africa this week.

How Washington will succeed in fine-tuning the complex moves required by such an ambitious set of policies remains a mystery; especially since, in a few weeks, the US will enter the most uncertain and potentially explosive presidential election campaign in the country's history.

Meanwhile, the US political establishment remains blindly wedded to the idea that the nation's main problems come from overseas, when the stark reality points to its internal polarisation. There is already a culture war; it could easily turn into a civil war.

Slam dunk

The US and the UK sold the crushing of Russia in Ukraine as a slam dunk. Massive sanctions were supposed to have brought Putin and his cohorts to their knees last summer, yet their impact seems to have been minimal.

Those sanctions have been enthusiastically and blindly embraced by Europe, which inflicted on itself the third act of catastrophic self-harm in just over a century, after the First and Second World Wars.

The blowback of giving up cheap Russian gas supplies, together with protectionist US policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act, is pushing the old continent to the brink of de-industrialisation.

Provocatively, the Economist’s cover story last week asked: “Is Germany once again the sick man of Europe?”

The British magazine’s gloomy title sounds like a sort of mission accomplished for the Anglosphere in terms of curbing Eurasia's rise. Everybody is realising this - apart from the European chancelleries, and, particularly, Berlin’s.

After all, for almost a century, the Anglosphere’s top geopolitical priority has been preventing the rise of Eurasia (the so-called Heartland), which could have been accomplished by increasing economic integration among Germany, Russia and China. For the time being, Sir Halford Mackinder, Nicholas Spykman and Zbigniew Brzezinski will not be turning in their graves.

So far, then, the “slam dunk” on Russia has been as successful as the one that CIA director George Tenet sold to George W Bush in 2003 about Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.

US and China

The latest cold shower came last week from the Washington Post which, quoting US intelligence sources, presented a depressing picture of the effectiveness of Ukraine's counter-offensive. Both Russia and Ukraine will continue to bleed, but the latter seems more anaemic than the first.

The success of the policy to contain China still has major question marks. The feeling is that it is too late.

The US has been too complacent for too many decades in its outsourcing to China of its main supply chains. China has now become a bipartisan obsession in Washington.

The Biden administration has been frantically setting up political formats such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (US, India, Japan and Australia) and Aukus (Australia, the UK and the US), aimed at containing Beijing. The latter will land Australia an astronomical bill of between $268bn and $368bn, just to have a few nuclear submarines and 20,000 new jobs.

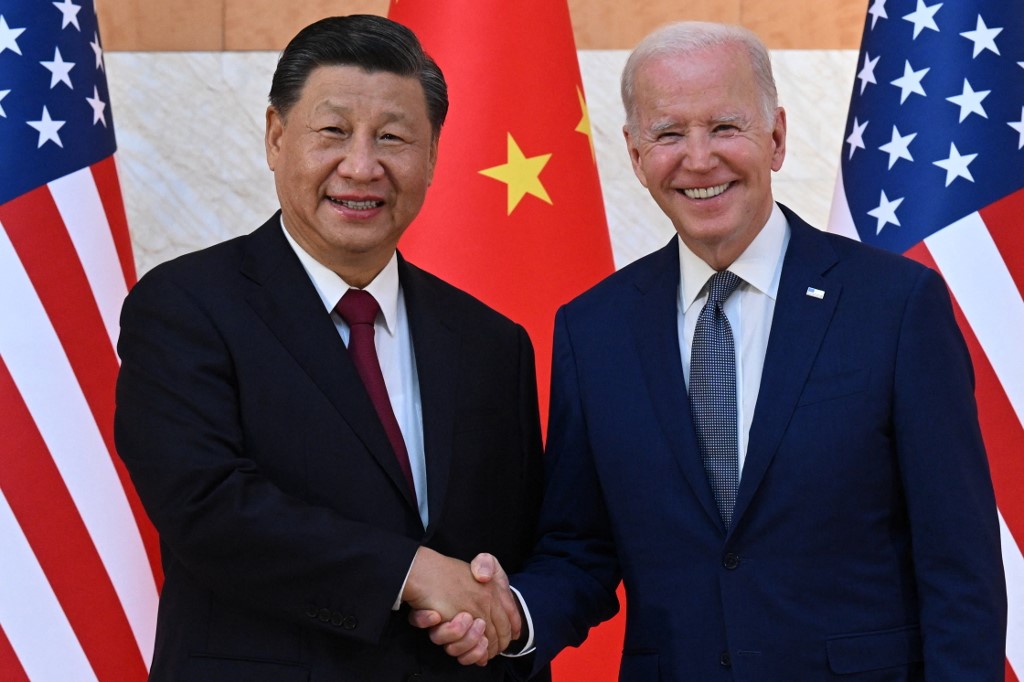

Last week, Biden hosted Japanese and South Korean leaders at Camp David to reinforce trilateral coordination aimed at keeping China at bay. For all practical purposes, the US's four-decades-old “one China policy” is now defunct. From the Chinese leadership’s perspective, this implies a potential war over the future of Taiwan, with the island being the world's top producer of the microchips essential for the ongoing fourth industrial revolution.

The move with China will be a long game. Historically and culturally, China excels in such plays; America (with the added factor of a now openly dysfunctional political system), on the other hand, does not.

The move with China will be a long game. Historically and culturally, China excels in such plays; America, on the other hand, does not

Decoupling from China is easy to declare but difficult to achieve. Even one of the top exponents of the US military-industrial complex, the CEO of Raytheon, Greg Hayes, has candidly admitted that the US cannot decouple from China, even its military industry, but should de-risk.

As for that de-risking, the top State Department official in charge of China policy, Daniel Kritenbrink - on the record in front of Congress - was not able to explain the difference between derisking and decoupling.

Re-onshoring chip manufacturing to the US, Biden’s top priority, is a headache. It would be difficult to find in the US the necessary skills to set up an advanced manufacturing plant. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company is delaying the plant it has been commissioned to build in Arizona because of a skilled worker shortage.

It is also becoming more and more evident that the most important supplier for the green energy transition is now China. It is tragicomic, considering how much the US pressured its European allies to give up cheap Russian gas to end up completely dependent on China for green energy.

Complex mosaic

As for the Middle East, over the last 20 years America has been exposed to a sequence of shocks. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq achieved nothing. Years of sanctions and maximum pressure against Iran have only deteriorated the strategic equation to the US's and Israel's disadvantage.

By signing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2015, Iran had committed to a 3.67 percent uranium enrichment process intrusively monitored by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Today, the US is looking for interim deals with Iran where the latter would not exceed a 60 percent limit, i.e. a few steps away from the military ceiling, with an exponentially increased uranium stock.

Washington is now trying to de-escalate the dangerous situation with Iran through ad hoc arrangements, including the exchange of prisoners and some modest sanctions relief. At the same time, it is trying to lure Saudi Arabia into joining the Abraham Accords, which are becoming more and more unpopular in the Arab world due to Israel's brutal policies against the Palestinians and its relentless settlement activity.

In exchange, Riyadh would get a vague Nato-style security pact with the US, a massive weapons procurement, US support in developing a civilian nuclear programme, and some unspecified Israeli “concessions” to keep the two-state solution for the Palestinian question alive.

There seem to be too many pieces to be placed in such a complex mosaic. On weapons procurement and a Saudi civilian nuclear programme, Israel and its supporters in the US Congress might raise more than one objection.

Such a trilateral agreement has two specific purposes: further isolating Iran and complicating Saudi Arabia and China's evolving relationship.

So, on one side the Biden administration is attempting to de-escalate with Iran and delay any major decisions until after the 2024 presidential elections and, at the same time, is pursuing policies aimed at isolating Tehran.

It is unclear if Iran and China will remain idle while the US administration is working to “sabotage” the Saudi-Iranian and Saudi-China tracks. Saudi-Iranian defence talks took place recently in Moscow; Saudi Arabia and China are signing major infrastructure deals, and Iran's foreign minister has just been received by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Meanwhile, Israel, the cornerstone of US policy in the Middle East, is slowly sliding into an autocracy through the controversial judicial reforms that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is imposing on the country.

If US diplomacy is to succeed in squaring this complex circle, it would mean that Team Biden’s diplomatic capabilities are far better than previously imagined. We will see.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.