US democracy will survive, but not as an example for the Middle East

Is democracy dying in the United States? Is the country on the verge of civil war given that some 75 percent of Republican voters still refuse to accept the results of the duly certified 2020 presidential elections? Is a repeat of the January 2021 assault on the Capitol likely?

Relax: these ideas make for good headlines, but do not reflect accurately what is happening in the US. If the Middle East is going to be affected by developments in the US, it will be affected by what is actually happening, not by doomsday predictions.

There is no doubt that the US is deeply divided today, but no more so than at other times in the past. Americans fought a four-year civil war from April 1861 to April 1865 and not all scars of that experience have healed: what Americans in the north of the country call the civil war is still “the war of northern aggression” for their compatriots in the south.

The introduction of the so-called Jim Crow laws that deprived the African-American population in the south of their newly recognised rights perpetuated racial divisions after the Civil War. Americans were also divided in the 1930s by President Franklin D Roosevelt's New Deal.

During the 1950s, following a decision by the Supreme Court that “separate but equal” schools were unconstitutional, the federal government sent heavily armed troops to escort black children into previously all-white schools, creating much resentment in the south without substantially decreasing racial discrimination.

The US was again torn apart in the early 1960s, when battles for civil rights raged in the south and when northern cities exploded into riots every summer. The battles of that period led to the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but it was not the end of the story. In 2021, after President Donald Trump was defeated in his re-election bid, Republican-controlled legislatures in more than half the states introduced new laws that aimed at making it more difficult for people to vote, under the guise of safeguarding the non-threatened security of elections.

Finally, it is important also to recall that the Vietnam War pitted Americans against each other and undermined confidence in the government.

Stoking the flames of resentment

Divisions in the American body politic are thus a constant theme of US history, but only once in 240 years have they threatened the integrity of the country or destroyed its political system. Current divisions are no more threatening than most in the past, even as many politicians, led by Trump, are doing their best to stoke the flames of anger and resentment.

This does not mean that unity and faith in the democratic political system and the country’s institutions will be restored quickly. A segment of the population that feels discriminated against and overlooked has come out in the open and gained a new voice, with Trump’s encouragement.

The new disenchanted and aggrieved are not the racial minorities that have always suffered from discrimination… they are members of the mostly white working class

The new disenchanted and aggrieved are not the racial minorities that have always suffered from discrimination, nor are they the very poor (although their problems are serious and need to be addressed). Rather the new aggrieved are members of the mostly white working class. These are people who had, over a couple of generations, become used to well-paying industrial jobs that did not require higher education, enjoyed middle-class standards of living and feel entitled to it, but are finding it difficult to maintain their position in the new economy.

Industrial jobs have become scarce, with many relocated offshore - in China and other East Asian countries, across the border in Mexico, and in general in countries where labour costs are lower. For people with limited education, the fact that the economy produces many more openings in well-paying positions requiring skills they do not have and do not think they can acquire is no compensation for what they have lost.

The frustrations deriving from this fundamental problem are manifested in the myriad ways that drive wedges among Americans.

One is the animosity toward immigrants, accused of taking jobs from real Americans, many of whom would not touch the jobs most immigrants perform, from construction to restaurant work.

Another is the bitterness of the battles about what schools should teach. These battles are leading to the banning of books and the firing of teachers and principals accused of making white students feel bad about themselves by discussing US history as it is in its reality rather than in an idealised form.

Democracy far from dead

More generally, the country is shaken by the tendency of many to believe that everything is conspiring against them, from vaccination mandates to vote-counting. This is the new element in the present disunity in the US.

Despite these divisions, democracy is far from dead. In the 2020 elections, more people voted than at any time before. Those parents who stand up and fulminate against the education their children are getting in public school are exercising democratic rights that go beyond merely voting in elections - even if one disagrees with the specific content of their complaints.

True, the refusal to accept the results of duly certified elections even after multiple investigations and court challenges is a threat to democracy, because democracy requires citizens to accept the defeat of the candidates and ideas they supported. But what happened after one election is not enough to cry over the demise of the entire system. American democracy has survived many challenges and will most probably survive this one as well.

Implications for the Middle East

For people in the Middle East, the biggest challenge posed by the situation in the US does not stem from the internal conflict and divisions. Rather, the challenge comes from a view shared by most policymakers in Washington, no matter which party they belong to: the US should start paying less attention to the Middle East and pivot its attention to Asia, because that region is much more important to the security and economic wellbeing of the US now that it no longer needs to import oil.

George W Bush was the last US president to put the Middle East - or, better, the greater Middle East - at the centre of US policy, when he ordered the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq.

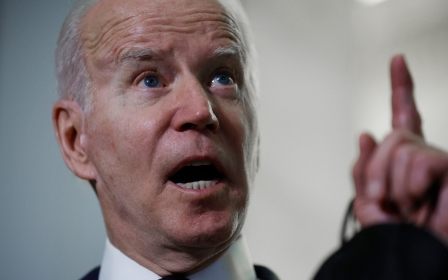

All of his successors - Barack Obama, Trump, Joe Biden - have tried to reduce US commitment to the region. Even those who now decry the US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the subsequent takeover by the Taliban do not really advocate that the US should stay indefinitely, but only argue that it should have withdrawn without allowing the Taliban to come to power - without specifying how that could have been accomplished.

A view shared by most policymakers in Washington is that the US should start paying less attention to the Middle East and pivot its attention to Asia instead

As long as the US perceives Iran to be a danger, the pivot to Asia will remain partial at best. Should Iran sign a new treaty with the US and European countries to replace the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal undermined by Trump’s 2018 decision to withdraw from it, US presence in the Middle East would diminish rapidly.

For Arabs who have been railing against US Middle East policy, with its real or imagined plots against Arab regimes, a decreased US presence in the region should be welcome. Unfortunately, it will not be.

Many Arabs who resent the US for what it has done in the Middle East also believe that America could solve many of the region’s problems if it wanted to. No matter how much or how little US involvement there will be, resentment against it is unlikely to decrease.

Supporting authoritarian regimes

Less American involvement will not have much direct impact on democracy in the Middle East, an already scant commodity.

The US has historically done little to encourage democratic change, supporting authoritarian regimes in the name of stability. In Iraq and Afghanistan, after the interventions following the terrorist attacks of September 11 2001, the US did try to stand up democratic regimes.

The outcome in Afghanistan is that the Taliban is back in power. The outcome is somewhat less disastrous in Iraq, where an elections-based system limps along, plagued by corruption and sectarian divisions. Both examples raise the fundamental question of whether the US knows how to promote democracy, and more generally whether democracy can ever be the result of outside pressure.

What may have an impact on the Middle East is the example of disarray the US presents to the world. The country will not implode, but it can no longer pretend to be the “shining city on a hill” that President Ronald Reagan imagined.

The bitter animosity dividing the country, the incapacity of rival parties to compromise and cooperate, and the disenchantment of many Americans - not only with a specific government, but more broadly with the overall political system - means that whatever shine the country may or may not have had, it is fast disappearing.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.