Why the US needs to cooperate with Russia and China

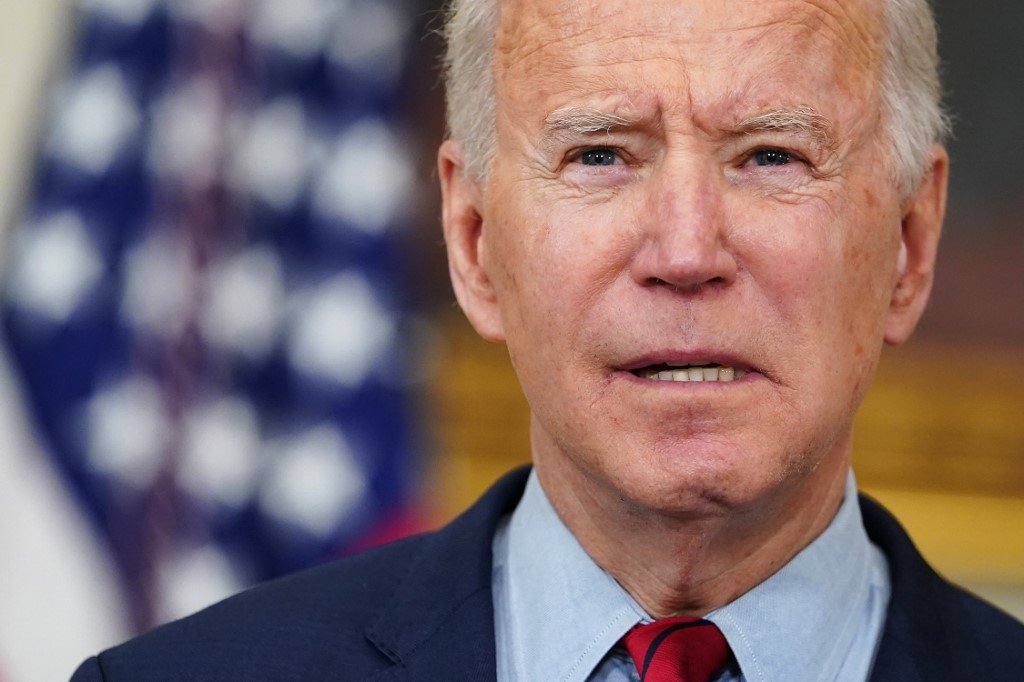

“America is back,” US President Joe Biden said solemnly in his first major foreign policy speech at the Munich Security Conference last month. In outlining more comprehensively his vision for how the US will engage with the world through an "Interim National Security Strategy Guidance", he added that the US will be “leading first with diplomacy”.

While it is worth wondering - after he called Russian President Vladimir Putin "a killer" - how Biden defines diplomacy, the strategy document is an interesting read.

US foreign policy seems to be in a transformational phase. In the last three decades, the world has adjusted to Washington’s bad analyses, which have resulted in mistaken, damaging and often self-harming policies. The Biden administration seems to be attempting a course correction; it is beginning to show some better analysis, but this is still unmatched, unfortunately, by sound corresponding policies. It is halfway towards “charting a new course”.

Shifting dynamics

In the strategy document’s introduction, Biden observes that the “world is at an inflection point” as “global dynamics have shifted”. He says the US must lead the world to “ensure the American people are able to live in peace, security, and prosperity”, emphasising that the US defends “equal rights of all people” to ensure “that those rights are protected for our own children here in America”. Yes, he wrote that.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

From a different political spectrum, diehard neocon Robert Kagan was recently even more explicit: “The time has come to tell Americans that there is no escape from global responsibility … They need to understand that the purpose of NATO and other alliances is to defend not against direct threats to US interests but against a breakdown of the order that best serves those interests.”

There still seems to be no chance that a truly multilateral approach to the world order may be considered in Washington

The psychological mechanism causing the most powerful nation on Earth - which has a massive military deployment surrounding its main alleged enemies - to be so obsessed with its national security eludes this author; it is perhaps a matter for university psychology departments.

Ordinary Americans, however, seem to think differently, with one recent poll showing that only eight percent believe the main threat to their way of life is abroad, while 54 percent point to “other people in America” - not China, not Russia, not Iran. They confirm what we will never tire of repeating: the biggest threat to the US, its democracy and values is inside the country, as seen by the more than 70 million Americans who voted for former President Donald Trump in the last election.

Biden (and Kagan) seem to be obliquely coming to the same conclusion, while remaining reluctant to draw the right lessons from it. Should their statements bring us to the disturbing notion that in order to maintain democracy at home, a US-enforced world order must remain in place?

Trading barbs

In the context framed by Biden of “an historic and fundamental debate about the future direction of our world”, and amid “shifting global dynamics”, there still seems to be no chance that a truly multilateral approach to the world order may be considered in Washington - and thus, no chance that such an order and its founding values could be something other than shaped, led and enforced by the US. Russia stopped subscribing to this view in 2007; China more recently.

Putin answered with irony Biden’s offensive remark, but he also recalled his ambassador to Washington, and then added something far more sobering by emphasising how Russians “have a different genetic and cultural-moral code from Americans".

At the same time, a similar theatrical dynamic was unfolding with China. The American and Chinese diplomatic delegations recently held their first meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, and the barbs they traded in front of a flabbergasted media pool were tense - particularly the heavy words pronounced by China’s top official, Yang Jiechi:

“I don’t think the overwhelming majority of countries in the world would recognise the universal values advocated by the United States, or that the opinions of the United States could represent international public opinion. And those countries would not recognise that the rules made by a small number of people would serve as the basis for the international order.”

In 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping went into the temple of the US-led liberal world order, the Davos World Economic Forum, to defend globalisation and, consequently, this very order, under which China has also thrived. Then, the threat was the iconoclastic fury of Trump. Four years later, the landscape has completely changed, but only serious cognitive dissonance could exclusively blame China, Russia or Iran for the dismal results.

Wasted opportunity

Coming into office, Biden had a chance to turn a page, setting at least a new semantic approach to channel this dialogue in a less confrontational fashion - but he wasted it. Was it really necessary, for example, to sanction 24 Chinese officials on the eve of the talks in Anchorage? Or to threaten Chinese oil supplies from Iran? Again, talking about “diplomacy first”, what kind of reaction could have been expected from Beijing?

A few, but highly reliable, voices in Washington have warned for years against demonisation of Russia and China, attempting to introduce more sound analysis and wisdom in US policy options - to no avail. The late Princeton and New York University professor, Stephen Cohen, highlighted the need to take into account Russia’s perceptions to come to an understanding; for this, he was smeared and marginalised.

Roughly the same treatment was meted out to diplomat Chas Freeman, the top American expert on China, who recently provided a masterful assessment of US-China dynamics, emphasising the core problem still haunting US foreign policy towards China and the rest of the world: “Americans have an inbuilt missionary impulse. We enjoy protecting, tutoring, lecturing, and hectoring other peoples on how to correct their character to approximate our idealized image of ourselves. We are offended when others insist on independence from us and on preserving their own political culture. China has never wavered in its determination to do both, wishful thinking by American politicians and pundits notwithstanding.”

In Anchorage, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken criticised China’s stance on Hong Kong, Taiwan and Xinjiang. To Beijing, the first is perceived as support for two centuries of British colonialism; the second as continuing US interference in fallout from the Chinese civil war; and the third as an intrusion on a matter of internal security against Islamic terrorism.

Global stability

As long as the US foreign policy matrix remains “it is either the American way or no way”, any improvement will be extremely difficult.

Unfortunately, such rhetoric is still not matched by consequential semantic and diplomatic approaches

Biden’s security strategy guidance document contains remarkable and brave improvements: “We cannot pretend the world can simply be restored to the way it was 75, 30, or even four years ago. We cannot just return to the way things were before. In foreign policy and national security, just as in domestic policy, we have to chart a new course.”

On the Middle East, “we do not believe that military force is the answer to the region’s challenges, and we will not give our partners … a blank check to pursue policies at odds with American interests and values”.

Unfortunately, such rhetoric is still not matched by consequential semantic and diplomatic approaches, and it is doubtful that the tough US approach is viable. Effective US-Russia-China cooperation is crucial for world stability; there is no escaping this fact.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.