The utter inefficacy of overbearing security laws

Several attacks by Muslim extremists over the past few months in Canada, Australia, and France have re-emphasised the place of “home-grown terrorism” in the political language of the Western world. From Ottawa to Paris, new legislative and financial investments are being made by governments to build up policing and security systems, marketed enthusiastically by their proponents as being vital to public safety.

The official rationale given for this ramping up in policing and surveillance is that such a strategy will mitigate terrorism and radicalisation. Yet, a closer look at the nature of these issues suggests that such overhanded security policies will eventually backfire.

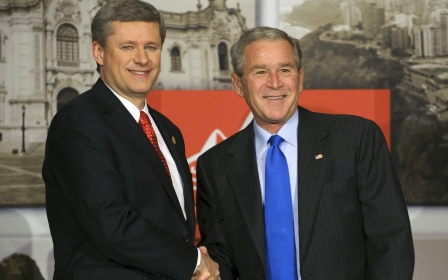

The new anti-terrorism legislation introduced last month in Canada by Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party is a case in point. The “Security of Canada Information Sharing Act” (or Bill C-51, as it’s now known) is the most sweeping set of laws proposed by a post-9/11 Canadian administration dealing with terrorism.

It coincides with Canada’s involvement in the bombing campaign against the “Islamic State” (six Canadian fighter jets and two surveillance jets are flying out of Kuwaiti airbases), which has been buttressed by a consistent post-9/11 rhetoric of fear. One way this narrative manifests itself within domestic Canadian politics is through how the threat of radicalisation and home-grown terrorism are being addressed by the government.

Bill C-51 is just the latest example. The proposed bill will, among other things, further expand the powers and mandate of the country’s spying agency, CSIS, while also seeking to criminalise “any materials that promote or encourage acts of terrorism against Canadians in general, or the commission of a specific attack against Canadians.” These laws are being tabled at a time when Canada has already constructed an overweight security apparatus that lacks civilian oversight.

Yasin Dwyer, who worked as a Muslim chaplain with the Canadian Correctional Services for 12 years, and with several terrorism offenders, has noted that the security-heavy approach is tough on crime, but not on the causes of crime. It doesn’t emphasise the need to get to the root of these problems, which, in his opinion, has much less to do with religious belief than with personal grievances and frustrations. Instead, governments are building massive structures to regulate the symptoms instead of treating the disease.

Canada is already part of the infamous “5-Eyes” surveillance alliance along with the US, UK, Australia, and New Zealand, and has taken huge steps to enhance the powers of policing and intelligence agencies within its borders. A section of the Snowden archive shows, for example, that the Communications Security Establishment (CSE, formerly CSEC) has been monitoring millions of Internet downloads with a programme codenamed Levitation.

This is just one aspect of what is essentially Canada’s own global surveillance apparatus, which will continue to grow if Bill C-51 becomes law. Documents unearthed by security and legal scholar Michael Geist show that Canadian telecommunications companies are disturbingly compliant when talking to the federal government about having to install surveillance and interception systems within their networks, and to divulge user data to the state when asked. Moreover, watchdogs from both inside and outside of government have warned that Canada’s anti-terror laws are endangering basic civil liberties.

The animating idea behind anti-terrorism right now is that more policing/surveillance equals more opportunities to foil terrorism plots before they’re carried out. A window opened in Canada after what happened last October (and after the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris) for many politicians in the West to return to a rhetoric of fear in order to climb up the polls. France has invested a large amount of resources into the country’s intelligence apparatus. Canada is doing the same thing. Yet there is no evidence to suggest that radicalisation and the threat of terrorism is on the rise in Canada.

What’s being ignored is the huge pile of evidence against the idea that heavy state security equals a safer public. One of the more thorough studies was done by the New America Foundation, which looked at 225 plots within the US since 9/11 that ended in successful convictions, kills or otherwise. It concluded that only four out of the hundreds of cases had anything substantive to do with the NSA’s massive collection of private metadata.

Moreover, studies from security and intelligence organisations such as the Soufan Group have emphasised that the most important way to mitigate radicalisation is to partner with grassroots groups that have a hand on the pulse of the community of interest.

Stephane Pressault, for example, is a project coordinator for the Canadian Council of Muslim Women (CCMW) who has worked with a large number of youth throughout Canada. He notes that the process of radicalisation is only truly noticeable by those close to the affected, and that such people should be incorporated into the solution - that security officials should be liaising a lot more with community members who have a sincere interest in public safety.

It is the only recognised way to understand the specific dynamics at work behind the very individualised and multi-dimensional trajectory of radicalisation; it’s impossible to get a handle on if the state is purposefully or inadvertently antagonising such communities monolithically.

And yet this is what’s happening right now between Muslim communities across the Western world and the governments they live under. A direct, though implicit connection is made between foreign policy vis-a-vis the Middle East and the domestic strategy to mitigate home-grown terrorism. The political narrative underpinning both spheres of policy is one of externalising all evil onto a particular group. In this case, the values that animate Muslim communities living in North America and Europe are being perceived as analogous to the ideologies that underpin the “Islamic State.”

This kind of paranoia and antagonism will breed further paranoia and antagonism within these communities, because such a narrative plays right into the hands of Muslim extremists who also promote a “West versus Islam” worldview. It’s exactly this type of mentality that must be avoided, and yet many governments are pushing policies that will only enhance its appeal.

- Steven Zhou is a regular contributor to Al Jazeera English, The American Conservative, Ricochet Media and Muftah, among other outlets. He also writes a regular column at The Islamic Monthly, where he's an associate editor. Follow him on Twitter @stevenzzhou

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.