Was Egypt's Morsi really an autocrat?

There has been renewed debate about the brief presidency of Mohamed Morsi, and about whether his and the Muslim Brotherhood’s attempt to monopolise governance in Egypt played a part in his downfall and in aborting the democratic transition.

This time the discussion is centred on the decision by Morsi to reject a suggestion made to him by Egyptians, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel and US President Barack Obama to ask Dr Mohamed ElBaradei or Amr Mousa to form a new government to replace that of Dr Hisham Qandil. The suggestion was made to him in the wake of the anxious ending to the crisis of the constitutional declaration in November-December 2012 and the formation of the Salvation Front that was opposed to Morsi’s rule.

Since both ElBaradei and Mousa were prominent leaders of the Salvation Front, the suggestion, it would seem, included the idea of inviting the Front to share power. Morsi’s repeated rejection of the idea, and the external pressures that accompanied that, are seen now as proof of his autocratic policy that consequently led to the escalation of the political crisis in the country and eventually to the coup of 3 July 2013.

The story about the Egyptian proposal, and the German and US lobbying behind it, is attributed to Abu Al-Ula Madi, leader of the Wasat Party. There is no reason why this story should be doubted. But there are also Egyptian political personalities, who are not Brotherhood members and who were known to have been close to Morsi at the time, who made the same proposal in April 2013 and heard from the president his own reasons for the refusal.

This is an issue I shall be returning to. The sequence of events shows that Madi was convinced by Morsi’s reasons for rejecting the proposal. This is so because relations between the Head of the Wasat Party and the president of the republic did not wane during the first six months of 2013; to the contrary they were bolstered further.

As for the external pressures, what is certain is that they centered around asking ElBaradei, and not Mousa, to head the government. On at least one occasion, when the new US secretary of state, John Kerry, met the Egyptian president in the latter’s office on Sunday 3 March, Morsi said that he did not believe ElBaradei was fit to head the government and that he did not trust his loyalty on the one hand or his ability to face pressures on the other, and therefore he could not simply jeopardise the future of the country in exchange for temporary political gains.

Morsi ruled the country for one year as of 30 June 2012. He governed in his capacity as a fully authorised president since the downfall of the military council’s authority in August 2012. Morsi commissioned engineer Hisham Qandil, the Minister of Irrigation in Al-Janzuri’s government, which was seen since Morsi assumed his mission as a caretaker government, to form a new government. Qandil, who had been in charge of the Irrigation Ministry since Sharaf’s government, was not a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. His first cabinet did not include more than four ministers who were members of the Brotherhood. Other parties were invited to propose their candidates for the cabinet and some agreed while others refused.

Qandil ended up forming a government that was comprised mostly of technocrats. This had been the custom especially since Sadat assumed the presidency. Morsi and his prime minister adhered to Egyptian traditions in appointing the ministers of defence, interior and foreign affairs from within the institutions of the military, the police and the diplomatic core.

On 3 May 2013, and after Morsi’s endeavours to achieve political concord and form a coalition government (and this will be discussed further later on) had failed, Qandil introduced changes to his cabinet. There were only nine ministers from within the Muslim Brotherhood in the new cabinet, which ran the country until the July coup. Out of a total of 36 ministers, 13 or 14 came from an Islamic background.

On 16 June, that is approximately two weeks before the coup, Morsi issued the list of new governors who included 10 members of the Muslim Brotherhood and two from two other parties out of a total of 28. As he did when he introduced the cabinet reshuffle, Morsi asked political parties to propose their own candidates for the governorship positions but only two parties cooperated with the President.

A few weeks before the last cabinet reshuffle, and specifically on 12 April 2013, Dr Ayman Nour, the prominent liberal figure and former presidential candidate in competition with Hosni Mubarak, received a phone call from the president’s office (and this is what Dr Ayman Nour said to me on two different occasions without discrepancy except in terms of the additional details provided on the second occasion).

Nour was one of the founding members of the Salvation Front, but he left the front on 6 December after it was agreed to nullify the November 2012 constitutional declaration and to issue a new declaration. Nevertheless, Nour still maintained amicable ties with his colleagues in the Front’s leadership: ElBaradei, Mousa, Hamdin Sabbahi and Sayyid Badawi.

On the following day, 13 April, Nour met with Morsi. The two men discussed the political situation in the country. Nour proposed to Morsi that he should ask Mousa or ElBaradei to form a new government. Morsi did not feel inclined toward any of the two; ElBaradei because he did not trust his abilities and Mousa because he believed that asking him to form the government would generate a new political storm considering that he was from the old regime. What Morsi did was to ask Nour himself to form a government.

In the beginning, Nour objected because the time remaining until the parliamentary elections was short indeed. He explained that perhaps there was no need for a new government. But Morsi assured him that he would keep the premiership after the elections in case the bloc of parties that supported the president end up winning. When Nour said that his party could not shoulder the burden of government and that he would work for forming a coalition government, the president agreed immediately and stressed that he would not impose on Nour any list of Muslim Brotherhood ministers and that he would not intervene in his selection of his ministers.

Nour then went ahead and started communicating with his former colleagues in the Salvation Front inviting them to participate in a coalition government. However, and in spite of the limited and cautious responses on the first day, leaking the news of the formation of a new cabinet on the following day led to hindering the efforts made to form the aspired government. On 15 April, Nour came back to the president to announce his decision to apologise and refrain from undertaking the task commissioned to him.

In all these events, and throughout the one year of his short presidency, Morsi never tried, in any way or form, to implant Brotherhood or Islamic elements inside the state apparatus, the bureaucratic body of the state. As is testified to by those who were close to him, he had no project or intentions for doing this.

During the months that followed his downfall, Muslim Brotherhood elements, or other Islamic ones, left their positions inside the state apparatus or were sacked or detained or killed. These included university professors, scientists, scholars, doctors, teachers, journalists or people in other professions. They had been occupying their positions naturally and in accordance with the state traditions and not owing to Morsi’s presidency. The appointments of ministers or governors, and the appointments of their advisors or assistants, were all, just like the advisers and aides of the president himself, purely political appointments, just like all the political appointments in other democracies; they had nothing whatsoever to do with the state apparatus or its bureaucracy.

This is not the story of a president who sought to rule alone or desired to act autocratically. Charging him today with such things, for this or that reason, shifts to the wrong place the search into the reality of the setback that Egypt has seen in the process of its democratic transition.

What caused the setback was actually the short-sightedness and stupidity of the opposition, particularly the Salvation Front, both the politicians and the activists. It was this that paved the way for the state coup against its elected president and against the entire democratic process.

- Basheer Nafi is a senior research fellow at Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

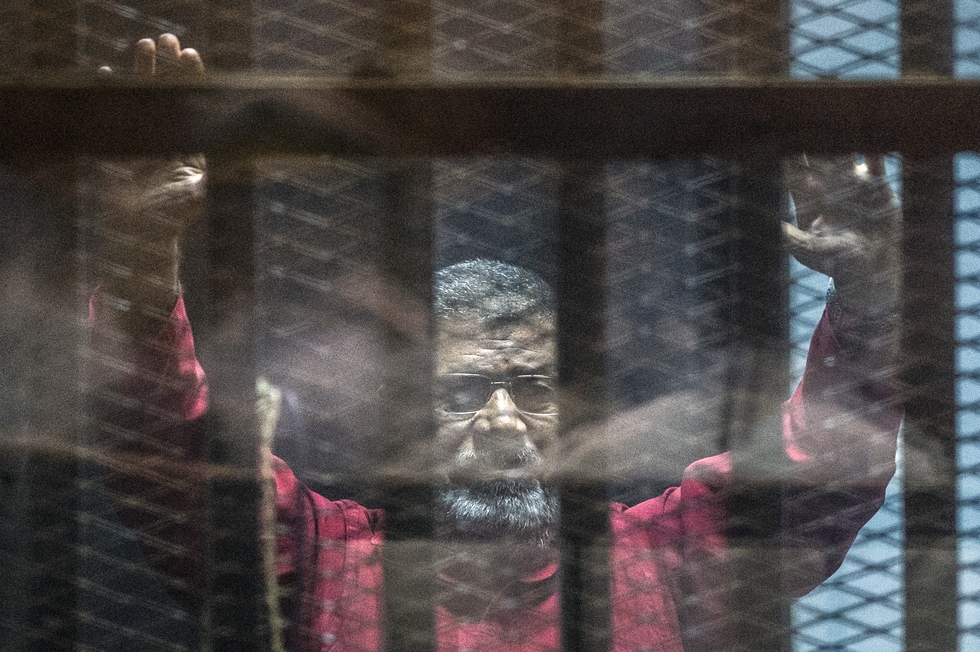

Photo: Former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi gestures from behind bars during his trial at the police academy in Cairo on 23 April, 2016 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.