What can Egypt take from the torture report?

His 18-year-old hands were cuffed behind his back, he was blindfolded and then taken in by Egyptian security officials for interrogation. During the interrogations, he was beaten and given electric shocks to his back, hands and testicles for around four hours until he “confessed” to crimes he now denies.

This is not a story from the US Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) rendition programme, in which Egypt played a significant role. It is a story from Egypt this year; on 25 January, 2014, to be precise. It is the story of Mahmoud Hussien, a student arrested for wearing, of all things, a ‘Nation Without Torture Campaign’ t-shirt and a scarf with the ‘25 January Revolution’ logo. He has been in prison for nearly a year on charges that include belonging to the banned Muslim Brotherhood group. He has yet to face trial.

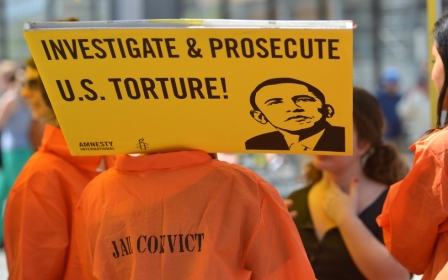

If the release this week of a report by the US intelligence’s oversight agency, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, teaches Egypt and the world anything, it is that torture is a failed and misleading mechanism for gathering accurate intelligence.

Former directors of the CIA - which is the subject of the highly critical report - argue that their torture methods, or “enhanced interrogation techniques” as they call it, gathered significant intelligence on groups such as al-Qaeda. This intelligence in turn prevented the recurrence of attacks like that of 11 September 2001, the largest attack on US soil in its history, or so the argument goes.

This may be true (although the report severely undermines any such claims), but in the wake of the report it must be acknowledged that due to the ‘enhanced interrogation techniques’ programme, more brutal threats have emerged - including the rise of the Islamic State.

Ali Muhamed Abdul Aziz al-Fakhiri, also known as Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, is a case in point. The Libyan national was arrested within a few months of 11 September 2001 in Pakistan, and after interrogations by the CIA he was extraordinarily rendered to Egypt in January 2002.

Egypt’s interrogation involved him being placed in a small box - 50cm by 50cm - for about 17 hours, and punched and beaten until he came up with a story that three al-Qaeda members went to Iraq to learn about nuclear weapons.

In 2003, then secretary of state Colin Powel relied on this fabricated information in his speech to the United Nations that made the case for war against Iraq. The war was based on a lie coerced from a detainee under torture. It was in the course of that war that groups such as the Islamic State emerged.

Egypt “has been the country to which the greatest numbers of rendered suspects have been sent”, Human Rights Watch said in its 2005 report on the fate of rendered Islamists.

Fifty-three other countries played their part. Some hosted secret CIA prisons, while others played a facilitation role, according to the Globalising Torture report compiled by the Open Society Justice Initiative funded by billionaire investor and philanthropist George Soros to promote government accountability. The senate report redacts the names of foreign countries that cooperated with the CIA’s rendition operations.

Egypt didn’t host secret CIA prisons, but it did detain and torture individuals subjected for extraordinary rendition, and transferred these individuals to other countries, as well as permitting the use of its airspace and airports for flights associated with CIA renditions. Egyptian authorities carried out the interrogations themselves and declined requests by US intelligence agents to question the individuals.

Roots of rendition

It all began in 1995, under the administration of US President Bill Clinton, when Egypt was approached by the US about becoming a partner in the rendition programme. Egypt accepted the invitation because it wanted access to Egyptian al-Qaeda suspects, while making use of US resources to track, capture and transfer suspects around the world.

This was at a time when Egypt was fighting what it claimed to be an ‘Islamist’ insurgency at home. Groups such as Jama’a al-Islamiya and Islamic Jihad had waged a number of attacks on senior government officials including the assassination of former president Anwar al-Sadat in 1981. This was followed by an attempted assassination of the former Interior Minister in 1993, and of former President Hosni Mubarak in 1995, as well as repeated attacks on tourists and Christians. These culminated in the 1997 Luxor massacre, when gunmen opened fire and killed 58 tourists and four Egyptians.

Foreign governments conveniently turned a blind eye to what was happening in Egypt. Sweden handed Egyptian nationals Ahmed Agiza and Muhammed al-Zery over to CIA agents in 2001, who then rendered them to Egypt, despite the risk of torture.

The two Egyptians had applied for asylum in Sweden. Yet, Agiza was subject to electric shocks while in Egyptian custody, and al-Zery was forced to lie on an electrified bed frame. There are also allegations that Australian officials witnessed the mistreatment of Australian national Mamdouh Habib after his rendition to Egypt, but failed to intervene on his behalf.

Between 2001 and 2005, the US transferred 60 to 70 individuals to Egypt in the context of the “war on terror”, according to an acknowledgment by former Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif.

Cairo’s Tora prison was one of the facilities used to detain extraordinary rendered individuals. Today, that prison hosts thousands of political detainees, including blogger Alaa Abdel Fattah, members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and scores of journalists, among them the Al-Jazeera three.

In May, Amnesty International found that dozens of civilians had been subjected to enforced disappearance and held for months in secret detention at an Egyptian military camp, where they are subject to torture and other ill-treatment, aimed at making them confess to crimes.

“They took off my clothes and gave me electric shocks all over my body during the investigations, including on my testicles, and beat me with batons and military shoes,” one former prisoner of the camp said. “They handcuffed me from behind and hung me on a door for 30 minutes. They always blindfolded me during the investigations. In one interrogation, they burned my beard with a lighter.”

The detainee was eventually released from the camp after 76 days without seeing a judge or a prosecutor.

The US Senate report is unequivocal in its condemnation of enhanced interrogation techniques, or the use of torture, which also include waterboarding, forced rectal feeding and sleep deprivation. In its 6,700 pages, of which only 525 have been declassified, its first finding and conclusion is that the CIA’s use of these techniques were “not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees”.

As Egypt is in the midst of its own “war on terror” against the Muslim Brotherhood (which it has deemed a terrorist group),as well as Sinai-based insurgents who have recently pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, and thousands of others whom it deems a threat, it would do well to heed the findings of the US Senate’s report.

- Nadine Marroushi is a British-Palestinian journalist who has worked for Bloomberg and the English edition of Al-Masry Al-Youm (also known as Egypt Independent), and as a freelance journalist has written for The National newspaper in the UAE, and the London Review of Books blog. She has also been published by the Financial Times, and other international publications.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo Credit: An Egyptian woman holds up picture widely circulated as alleged torture victim Khaled Said during a demonstration after Friday prayers in Alexandria on 25 June 2010, against the alleged killing of 28-year-old Said at the hands of police. (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.