What is Japan's strategy in the Middle East?

There were plenty of talking points after the recent G20 Summit in Osaka, Japan. US President Donald Trump made light of Russia’s meddling in US elections.

Out of the blue, Trump also offered to meet North Korean leader Kim Jong-un by the demilitarised zone between the north and the south. There was also no resolution to the US-Iran impasse.

These developments highlight the role of Japan, the host of this year’s summit, and its attempt to bolster its presence in the Middle East.

Energy needs

Just two weeks before the G20 Summit, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Iran, the first Japanese premier to do so since 1979, only to make a failed and thankless bid to mediate between Washington and Tehran. In April, Japan’s foreign minister, Taro Kono, visited Saudi Arabia, and then hosted Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif the following month.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Japan's relationship with the US is the cornerstone of its security. Yet, the often-unpredictable policies of the Republican president have unnerved Tokyo

Japan’s need for energy is the main driver of its increased involvement in the Middle East. Japan’s energy dependency intensified after the decision to halt its domestic nuclear energy programme following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear calamity, the world’s worst nuclear accident since the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. Since then, the Middle East has accounted for almost 90 percent of Japan’s oil imports, primarily from Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

But Iranian oil is cheaper and therefore of considerable interest to Japanese buyers. The 2015 Iran nuclear deal offered Japan Iranian oil, as well as trade opportunities in an emerging market that promised the opportunity for Japanese companies to win tenders for infrastructural development projects.

No wonder Trump’s decision to scrap the nuclear deal and reinstate sanctions was a source of consternation in Japan. And that’s not the only aspect of Trump’s foreign policy that worries Tokyo.

Diplomatic overtures

Japan’s relationship with the US is the cornerstone of its security. Yet, the often-unpredictable policies of the Republican president have unnerved Tokyo. Trump’s diplomatic overtures towards North Korea, and his direct engagement with Kim, which led to a historic summit in June 2018, have caught Japan off-guard.

So, too, did Trump’s previous statement that it was time for Japan and South Korea to defend themselves and his suggestion of halting joint military drills between the US and South Korea. This is while Tokyo watches China with increasing concern: the majority of Japan’s oil and gas arrives through the South China Sea, where Beijing’s navy is asserting its dominance. China is also increasingly investing in the Middle East.

In order to counter Chinese influence, Japan seeks to utilise its soft power. Unlike the US, France and the UK, Japan does not have a legacy of superpower or colonial domination of the region.

During the last century, both nationalists and Islamists in countries such as Iran and Turkey have admired Japan for its ability to modernise while retaining its traditional culture, according to several academic accounts. Meanwhile, Japan has been careful to maintain friendly relations with the Muslim world.

Humanitarian aid

After Trump decided to recognise Jerusalem as Israel’s capital in 2017, Japan refused to follow suit, and dispatched its foreign minister to the region. Kono has vocalised his opinion that Japan should take in more Syrian refugees, and Japan has donated more than $100m in humanitarian assistance for Syria and $320m to the Middle East in general.

Japan also supported the fight against the Islamic State, which murdered Japanese journalist Kenji Goto and held captive several other Japanese nationals.

Japan also plays a pivotal role in the ongoing Valley of Peace initiative, which involves identifying and creating industrial zones between Israel, the Palestinian territories and Jordan for mutually beneficial collaborative infrastructural and development projects.

All this is small fry, however, compared to China. Sure, Japan has cultural capital and a fair amount of goodwill, but China is a world power with a large standing army. It is undeterred by constitutional prohibitions for offensive deployment of military forces, is in possession of a nuclear arsenal, and has a permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council.

China also has more capital at its disposal. Beijing seeks to expand its influence in the Middle East through loans and aid packages, in the form of the New Silk Road initiative.

In 2018 alone, Beijing pledged $23bn in aid and loans and an additional $28bn in signed infrastructure and construction projects. Beijing has also opened a military base in Djibouti by the Gulf of Aden.

Worthwhile pursuits

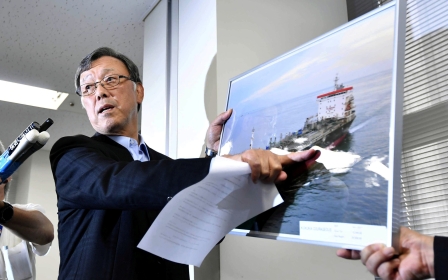

Developments in recent months have shown the limitations of Japanese influence in the Middle East and its ability to mediate conflict. Last month, two tankers were sabotaged off the coast of Oman - one of which was Japanese-owned - and the US recently deployed an aircraft carrier to the region, prompting Abe’s attempt to mediate. He was rebuffed by both Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and Trump.

It is beyond Tokyo's current ability to play a leadership role or to mediate conflict, let alone counter China's influence

It may be wise for Tokyo to accept the limitations of its influence. It is beyond Tokyo’s current ability to play a leadership role or to mediate conflict, let alone counter China’s influence.

However, this does not mean that Tokyo should retreat from the Middle East. Japanese expertise, trade and investment would be welcomed in the region. This will no doubt lead to additional goodwill, increased trade and the winning of tenders. Surely, these alone are worthwhile pursuits.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in french on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.