What a town in Djibouti could teach Europe about refugees

Every debate on migration, either forced or economic, is built around numbers. Every migration or asylum policy is focused on figures, and often figures alone. More importantly, a host society’s hostility towards migrants and refugees gets politically legitimised if the number of newcomers is deemed high. But it does not have to be that way.

Why are all EU states currently resisting the relocation of asylum seekers from Greece and Italy?

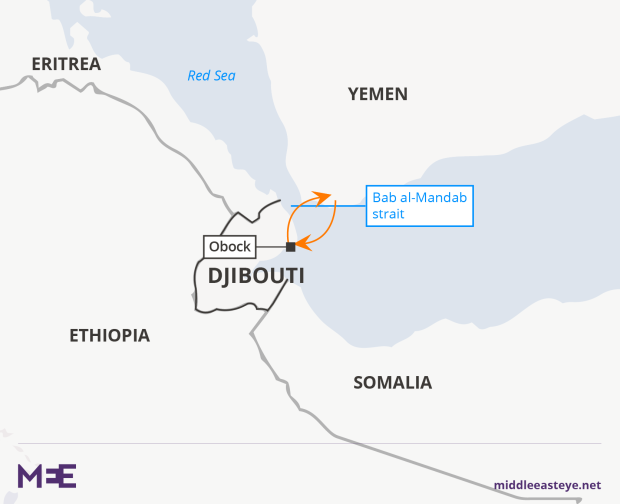

I worked for more than two months in Obock, a tiny town of 2,000 inhabitants in northern Djibouti. Located only a few hours across the Bab al-Mandab Strait from Yemen, Obock is a transit zone for both migrants and refugees. The town hosts Markazi, a Yemeni refugee camp of approximately 1,000 people, and at one point, there were also around 1,000 irregular Ethiopian migrants in Obock on their way to Saudi Arabia.

When I first arrived in this very poor, politically marginalised Afar community (a minority ethnic group in the country which is dominated by Somalis), there was an outbreak of acute watery diarrhoea, and some cases of cholera.

However, there were no tensions between the host population, refugees and migrants. Why can’t we even imagine a similar situation somewhere in Europe? Why are all European Union states currently resisting the relocation of asylum seekers from Greece and Italy?

Migration crossroads

Djibouti is one of the poorest countries in the world. More than 23 percent of the population of only 908,349 people live in extreme poverty, according to 2015 World Bank figures.

With less than 1,000 km2 of arable land (0.04 percent of 23,200 km2) and an average annual rainfall of 5.1 inches, Djibouti suffers from a chronic food deficit. As a result, 26 percent of children below the age of five are malnourished.

Despite all of this, as a result of its geographical proximity and historical links, Djibouti is also the primary destination for refugees fleeing war in Yemen. The tiny East African country also hosts more than 11,000 refugees, including many from Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia, in Ali Addeh, and just under 2,300 refugees in Holl Holl. These are both refugee camps where conditions are extremely harsh as a result of limited water resources and intense temperature fluctuations.Djibouti is also a very important hub for mixed migratory movements - population flows that include both economic migrants and those who need international protection - across the Red Sea, mainly through Obock in the northern part of the country.

Obock is unique in its location, marked by bi-directional movement of people: Yemenis cross the strait both ways depending on the security situation in their respective hometowns, while Ethiopians hope to make the crossing to the Arabian Peninsula. Irregular Ethiopian migrants - those who enter a country without neccessary authorisation or documentation - are also deported back to Obock and the surrounding area from southern Yemen.

The deportations that I witnessed coincided with the announcement of a state of emergency in Ethiopia in October 2016. Both those Ethiopians who still wanted to reach Saudi Arabia, and those who were returned from Yemen, were stranded in Obock for months, largely relying on help from the local population which has very limited resources.

There were no tensions between the local community, refugees and migrants. And this was when the overall number of refugees and migrants reached exactly the same figure as that of the host population

For a few weeks, the Migration Response Centre (MRC) in Obock, managed by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) in collaboration with the Djibouti Ministry of Interior, was not able to facilitate voluntary return of often very ill Ethiopians back to their home country as Addis Ababa did not permit IOM convoys to cross the border.

The outbreak of acute watery diarrhoea, with some cases of cholera confirmed among exhausted migrants - who had made most of their usually two-week-long journey from Ethiopia to Djibouti on foot in scorching 50-degrees heat with inadequate supplies of water and food - brought the situation in Obock to a critical point of emergency.

No backlash, no tensions

Six hundred people were crowded inside the centre, and another 300 were housed in makeshift tents outside the facility. There was a shortage of water needed for basic hygiene and sanitation necessary to contain the epidemic, nor were there enough latrines to cater for the needs of severely sick people. The centre was also understaffed.

Overall, as many as 40 percent of medical facilities in Djibouti are used by migrants. At the beginning of the diarrhoea outbreak in Obock, migrants were precluded from accessing a very basic local hospital as Djibouti authorities attempted to prioritise their citizens and registered refugees. But later the Ministry of Health revoked its initial decision as 90 percent of suspected cholera cases were recorded among Ethiopians.

In Obock, the smugglers - who were themselves largely refugees from Eritrea - belonged to an extremely impoverished community residing on the outskirts of the town called Fantahero.

Migrants who paid a higher price for their journey (in the range of $1,000-1,500) were offered water and food; those who paid less (between $200-300) had to ask for food from a local mosque or a restaurant, and try to earn some money by doing jobs such as loading and unloading twice-weekly ferries running between the capital city and Obock.

Apart from instances of chasing people who were begging away from the restaurant, and the mosque not permitting the migrants to wash themselves at their premises, there were no tensions between the local community, refugees and migrants. And this was when the overall number of refugees and migrants reached exactly the same figure as that of the host population.

Political will

Now let us go back to Europe, arguably one of the most wealthy and safe continents in the world. After the start of the so-called "refugee crisis" in September 2015, the European Council came up with a plan based on the principle of solidarity and burden-sharing which includes intra-EU temporary emergency relocation of asylum seekers who are "in clear need of international protection" from Greece and Italy, to help those countries at the borders of Europe cope with the pressure of hosting new arrivals.

It's not because we cannot afford or manage to take in refugees. It is simply because we do not want to welcome those people on our soil

In total, as a result of the council's first and second decisions, 39,600 persons were to be relocated from Italy and 66,400 from Greece. One year later, in September 2016, a decision was adopted allocating a remaining 54,000 places for the legal admission of Syrians from Turkey to the EU.

The council established a two-year timeframe to meet the targets. If all member states delivered on their obligations, relocating all those eligible in Italy and Greece would be feasible by September 2017. But this has not been the case and the current pace of relocation is still below the European Council-endorsed target of at least 3,000 monthly relocations from Greece, and at least 1,500 monthly relocations from Italy.

At the time of writing, pressure remains high in both Greece and Italy with less than 14 percent of asylum seekers relocated so far. France is the country that has relocated the largest number of applicants (2,758) so far, followed by Germany (2,626) and the Netherlands (1,486). The contrast, if you think back to Obock now, a town of 2,000 with 2,000 newcomers is, frankly, quite absurd.

The reception of refugees, in fact, has nothing to do with a country's resources, size or population. It is only a matter of political will. Having removed the notion of hospitality from our political discourse, we are faced with a seemingly rational paradigm of numbers, which, in reality, is not rational at all. It only projects a picture of a political space defined by deterrence, whereby we are not willing to offer safe haven to people who are fleeing human rights violations and war.

And that is not because we cannot afford it, or cannot manage it; it is simply because we do not want to welcome those people on our soil.

- Dr Natalia Paszkiewicz is an anthropologist with a particular interest in migration and refugee studies. She has been working with refugees for over ten years in the UK, Malta, Ethiopia and Djibouti.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Yemeni child shouts on 13 April 2015 at a refugee boarding facility run by the UN High Commission for Refugees at Obock, a small port town in Djibouti located on the northern shore of the Gulf of Tadjoura, where it opens out into the Gulf of Aden (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.