What’s next for Algeria’s protest movement?

This week, Algerian army chief Ahmed Gaid Salah demanded action to remove long-time president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, from office after weeks of mass protests.

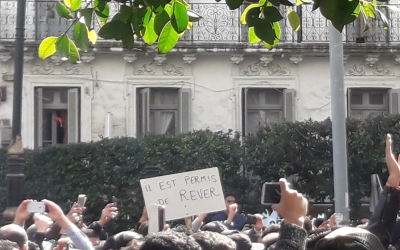

Soon afterwards, in a statement published by the Algeria Press Service, Bouteflika announced his immediate resignation. Thousands of Algerians celebrated in the streets to demonstrate their joy.

But this resignation is only the first step. Algerians still want to see the departure of Bouteflika’s entourage - of the old guard, including Gaid Salah. Algerians want a radical change in their leadership and political system. To keep up the momentum of the resistance movement, there are a few key steps that Algerians must take.

Goodbye, Bouteflika

Firstly, Algerians must stick to the demands they have put forward since protests began on 22 February. They must remain focused on removing Bouteflika and the old guard, ensuring a real change in leadership.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

A good analogy is the Bulldozer Revolution in Serbia, where the objective was unambiguous: to remove dictator Slobodan Milosevic from power. Despite the complexity and opacity of the Algerian regime, getting rid of Bouteflika and changing the country’s leadership can be attained.

After mobilising their core supporters within society, protesters must now start winning over the passive opposition and the pillars of power

The first part has already been achieved with Bouteflika’s resignation. Now, protesters must focus on getting rid of his entourage, including the new government he appointed before his resignation.

But opposition to Bouteflika’s clan and the leadership is not enough; the erosion of public support will force them to fall. But without institutional support, change may be difficult to achieve.

The protest movement has successfully rallied citizens of all ages, classes and regions, including students, professors, journalists, lawyers, judges and more. The heavyweight National Mujahideen Organisation, representing veterans of the liberation war, got on board and several MPs resigned to join the movement. More importantly, the ruling National Liberation Front last month announced its support for the movement.

Mobilising supporters

Algerians need to undermine their opponents’ support gradually. After mobilising their core supporters within society, protesters must now start winning over the passive opposition and the pillars of power.

There have already been signs of the possibility of convincing Algerian police. Many law enforcement officers happily joined the protests; some removed their helmets and left quietly, refusing to perform their duties, while others took to the streets, carrying signs with anti-regime slogans. The movement needs to convince more to defect.

Due to their experience and political maturity, Algerians see the protests as an excellent opportunity to build positive relations with the security forces. By keeping the protests civil, peaceful and agreeable towards the police, they could secure them as allies. This is crucial, because if the police are asked in the coming weeks to shoot into crowds, this relationship will be an important factor.

Any high-risk activism should be avoided. Protesters must continue their low-risk tactics, such as marching every Friday in a peaceful fashion, with children and seniors, chanting and dancing, humour and satire.

At the same time, Algerians should continue to disrupt bureaucracy. If judges, lawyers, doctors and civil servants refuse to carry out their functions, if oil and gas workers and merchants suspend their economic activities, if police officers and soldiers are convinced to stop obeying orders, Bouteflika’s clan will be handicapped.

Building local teams

Algerians are not using nonviolence out of a sense of moral commitment, but because they have learned from past experience that violent struggle would not be effective.

If the Algerian regime decides to use violence against unarmed protesters marching with their families, it will expose its brutality, undermining its legitimacy nationally and internationally.

Because mass protests are often fleeting, the movement needs to have a modicum of institutionalisation. The protesters do not want a leadership, and this is understandable; this avoids the leadership becoming media stars or being blackmailed, co-opted or jailed.

Yet, the movement needs to build its local capabilities. It should have local teams who can act independently, with autonomous branches throughout the country answering the national calls for coordinated action.

Local citizens should continue taking initiatives, allowing the movement to expand its reach - but all local actions should contribute to a unified strategy: structured yet decentralised, disruptive yet strategic.

The mobilisation remains significant and widespread. While radical regime change may be difficult, the status quo is already winding down. But one must be realistic. The institutional, social, economic and political devastation left by the regime will pose an immense challenge. The transition may be difficult and the progress towards democracy slow.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.