When I met the Muslim Brotherhood's Supreme Guide

Since my release from Guantanamo, I have found myself naturally interested in the stories of political prisoners around the world.

I’ve met colleagues of Nelson Mandela who were imprisoned on Robben Island; Irish Republicans who took part in hunger strikes with Bobby Sands; Palestinians who were imprisoned with their family members; and former prisoners in Libya, Syria and Egypt who spent decades in prison and emerged as leaders.

One of these men is the Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood, Mohammed Badie.

Egypt: Where the US threatened to send me

The Arab states of North Africa had never been a natural choice for me to visit after my release from Guantanamo.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The majority of the Guantanamo prisoners from this region were resettled in countries around the world, because even the US recognised that returning them here would immediately put them at risk of arbitrary imprisonment, torture and execution.

I was involved in resettlement discussions with European governments and met some of the prisoners after they were released. One was an Egyptian who’d been resettled in Slovakia. He didn’t return home for good reasons.

During the worst period of my interrogation by the CIA at the Bagram detention facility in Afghanistan, they threatened to send me to Egypt or Syria if I refused to cooperate, just as they had done with others.

There is a strong argument to suggest that the torture chambers of Egypt played a significant role in producing the leaders of some of the most dangerous militant groups in the region

One such prisoner was Saad Iqbal Madni, a Pakistani qari (Quran reciter) kidnapped by the CIA from Indonesia and secretly flown to Egypt via the British island of Diego Garcia.

Madni was imprisoned in Egypt for three months before being flown to Bagram, where I met him and learned about his ordeal. Even one of the interrogators at Bagram was Egyptian.

After his release from Guantanamo, Madni spoke about his years imprisoned without trial: “The place they put me in was smaller than a grave. In 92 days, I couldn’t lay down comfortably.

"They asked me questions about [the shoe bomber] Richard Reid, and if I had any information about 9/11. When I denied it, they gave me electric shocks in my knees. A few times I passed out.”

Egypt is notorious for torturing Muslims suspected of belonging to politically active Islamic movements.

Former CIA agent Robert Baer, who was assigned to the Middle East, knew about this fear better than most. He explained how the US utilised it: “If you want a serious interrogation, you send a prisoner to Jordan. If you want them to be tortured, you send them to Syria. If you want someone to disappear - never to see them again - you send them to Egypt.”

Ali al-Fakheri (aka Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi), a suspected Libyan al-Qaeda operative, was sent by the CIA for torture to Egypt under President Hosni Mubarak’s intelligence chief, Omar Suleiman.

Libi “confessed” that Iraq was amassing chemical weapons and giving them to al-Qaeda. This false intelligence was passed on to the US and became a key justification for the invasion of Iraq.

Return of the Pharaoh

Badie began his first stint in prison as a young man in 1965 for “political activity” after President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood. The next year, several leaders of the Brotherhood accused of plotting against the Nasser government were executed, including Islamic ideologue Sayyid Qutb.

Others received heavy prison sentences. One notable member of the Brotherhood was a woman, Zaynab al-Ghazali; she held a leading position in the Brotherhood and thousands attended her lectures.

In her prison memoir, Ayyam min Hayati (Days of My Life), later republished as Return of the Pharaoh, she gives a graphic personal account of the brutality of the Egyptian regime after her arrest in 1965.

Many of her students were brought in front of her and ordered to denounce her. They all refused.

Ghazali writes about how she witnessed her students “strapped to the post in the crucifixion position and beaten ferociously” in response. One of them was Badie; it was the start of his taste of Egypt’s prison system.

Despite being a civilian, Badie and his colleagues were tried by military tribunal. He received a 15-year sentence but was released after Nasser’s death following a general amnesty for the Brotherhood in 1974 by the new president, Anwar Sadat.

Torture and terror

There is a strong argument to suggest that the torture chambers of Egypt played a significant role in producing the leaders of some of the most dangerous militant groups in the region.

Badie went on to lecture at several universities and became a professor of veterinary pathology, but his work for the Brotherhood continued in earnest.

His organisation continued to call for Islamic reform and democratic elections, the latter being rejected by more militant Islamic groups, which were in ascendency after the vicious clampdowns.

Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was imprisoned after the assassination of Sadat in 1981. Although he supported a coup against the government, he was purportedly opposed to killing the Egyptian leader.

During a mass trial that lasted three years, Zawahiri told the court: “They put us in the dirty Egyptian jails … they whipped with electric cables, they shocked us with electricity! ... And they used wild dogs!”

The reference to dogs is something I’d heard many years ago. Unbelievably, Egyptian interrogators had trained dogs to rape prisoners. Zawahiri also named several prisoners who died after being tortured.

The Muslim Brotherhood did not adopt the path of political violence employed by Egyptian groups such as al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya or Tandhim al-Jihad, which Zawahiri went on to lead - but that did not stop them sharing a similar or even worse fate at the hands of the government.

In 1999, after another anti-Brotherhood crackdown under Mubarak, Badie and his colleagues were rearrested and prosecuted - again by military courts. He was released in 2003.

Meeting the Supreme Guide

In 2011, I travelled with journalist Yvonne Ridley to Egypt. My aim was to meet with any ex-prisoners or former intelligence officers who knew about the case of Fakheri and his tortured Iraq confession.

When I met Badie, I found him to be a very warm and likeable character. His years in prison hadn’t dampened his hopes for the future. Hundreds had been killed during anti-government protests, but Mubarak had stood down.

The Muslim Brotherhood was no longer illegal, and was about to enter the electoral process and finally get a chance to lead the country.

I questioned Badie on the Brotherhood’s cordial relations with the military; he believed that it was a necessary compromise for the greater good.

Badie didn’t know much about Fakheri, but he did tell me how he’d spent time in prison with three British prisoners convicted for membership of Hizb ut-Tahrir.

He told me how he’d interpreted a particularly memorable dream one of them had. I met all three after their return to the UK in 2006.

In 2012, the Brotherhood fielded the Freedom and Justice Party, with Mohamed Morsi at its head.

Morsi defeated all other candidates and emerged as Egypt’s first-ever democratically elected president. All the years of abuse, prison and torture had led to this moment in history - but it was short-lived.

Back in prison

The next year, the same military that prosecuted Badie as a teenager now orchestrated a coup against Morsi, with deadly consequences. Once again, the Brotherhood was outlawed. This time, it would not be spared.

Mass unrest followed the ousting, and hundreds were killed in demonstrations and counter-demonstrations. Hundreds of people were killed during the Rabaa massacre, when Egyptian security services opened fire on thousands of Morsi supporters.

Almost the entire leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood was imprisoned, while others were killed, including Badie’s own son.

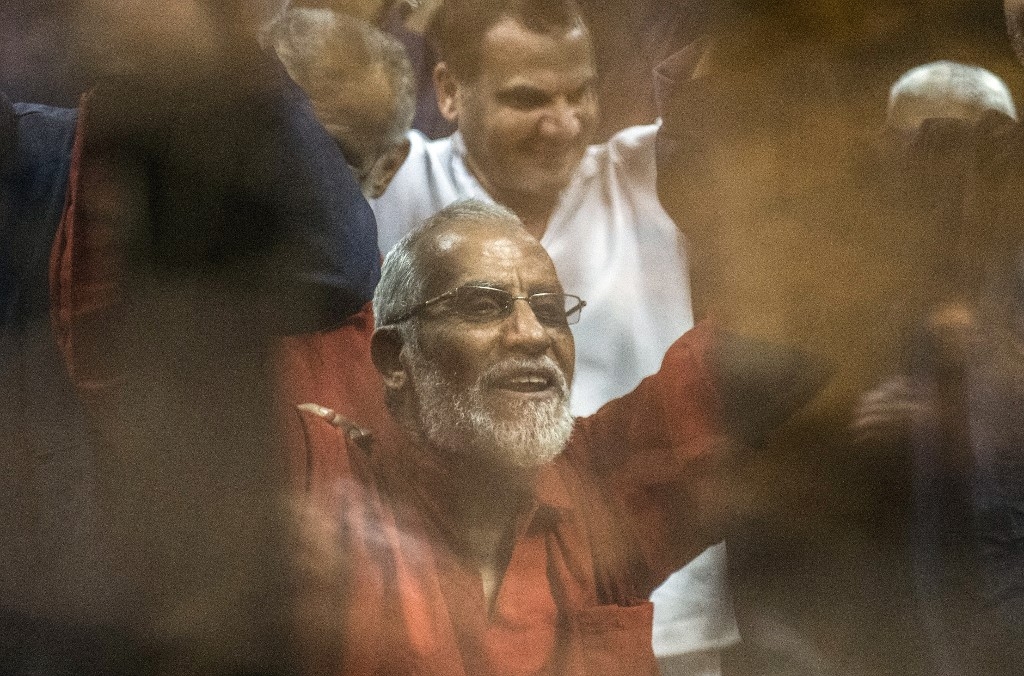

Badie went into hiding, but was arrested in 2013 and sentenced to death in a mass trial, along with 682 others. He subsequently received additional death and life imprisonment sentences, and has appeared in court almost every year since to face more charges.

Meanwhile, Mohammed Akef, former head of the Muslim Brotherhood, and Morsi both died in prison.

Whether he dies free or a prisoner, history will remember him for who he was and what was done to him

Badie is now 76, and has spent almost two decades of his life in prison for his political beliefs.

According to his daughter, he is denied family visits, and his medical status is unknown. He sleeps on the floor in solitary confinement and, if the government has its way, he’ll die there.

You may not agree with the Muslim Brotherhood, but there is no escaping the fact that this organisation and its members have been put through unimaginable hardships and torture.

Badie could have given up after his first prison encounter, but he chose to fight on.

Prison didn’t weaken him; it only strengthened his resolve. Whether he dies free or a prisoner, history will remember him for who he was and what was done to him. And others will surely walk his path.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.