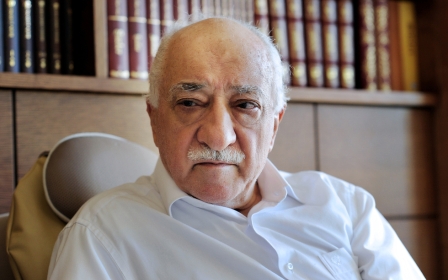

Who is Fetullah Gulen?

Debate is raging in Turkey over what role, if any, self-exiled Islamic cleric Fetullah Gulen and his throngs of supporters in government jobs played in last week’s abortive coup. But one man has little doubt of Gulen’s guilt - his former second-in-command.

Together Gulen and Latif Erdogan - no relation of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan - built the Hizmet (Service) movement, which has since infiltrated the army, the judiciary, the prosecutors’ offices, and the wider civil service.

“When it failed, Gulen told the media 'I opposed the coup' - but I know that every stage the coup plan was edited and approved by him”, Latif Erdogan told the newspaper Vatan.

“Hundreds of people would have died if the coup had been successful. The country would have slipped inevitably into civil war. Gulen is a cruel, cruel man. Turkey has avoided catastrophe. They didn’t expect people to take to the streets to defy the tanks."

President Erdogan is of the same opinion, and has launched a massive purge of the army and civil service aimed at rooting out Gulenists.

Latif Erdogan worked with Gulen for over three decades to build the Hizmet movement, which started as an educational network that encouraged its former students to enter the judiciary, prosecutors’ offices, civil service and even the army. Until five years ago he was widely considered Gulen’s heir presumptive, regularly traveling from Istanbul to visit the cleric at the rural estate in Pennsylvania where Gulen has lived since 1999.

Latif Erdogan split after concluding that Gulen was no longer simply trying to spread the ideals of honesty and incorruptibility into public life, but was moving into direct opposition to Turkey’s ruling Islamists, the Justice and Development party (AKP) of President Erdogan.

He says the change came in part when Gulen took up residence in the US and established links with neo-cons, as well as the CIA and the Israeli spy agency, Mossad. Gulen takes a hardline and critical stance on Russia and Iran, as well being broadly supportive of Israel. Gulen’s first public disagreement with the AKP emerged after Israel’s attack on the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish aid ship for Gaza, in 2010.

Nine people died when Israeli commandos boarded the ship in international waters. Turkey down-graded relations with Israel and they were only restored earlier this month, but at the time Gulen criticised the organisers of the aid flotilla for provocative behaviour and Recep Tayyip Erdogan for over-reacting.

Gulen also opposed the AKP for opening peace talks with the Kurdish nationalist movement, the PKK. His followers are accused of leaking tapes in 2011 which showed Hakan Fidan, the head of national intelligence, holding secret talks in Oslo with the PKK. The overtures to the PKK, which led to a ceasefire in southeastern Turkey, upset many in the Turkish military who felt that softening-up on the fight against the PKK undermined the national interest.

The issue revealed signs of a convergence between Gulen and the military, even though in the two previous decades Gulen supporters had played a major role alongside the AKP in reducing the military’s interventions in politics and sacking generals loyal to the secular legacy of modern Turkey’s founding father, Kemal Ataturk.

Some critics of the Gulen movement say its relationship to the military high command was ambiguous, even when senior generals were avowedly secular and suspicious of Islamists. During the army’s successful coup in 1980 Gulen praised it, a stance that lessened the generals’ wariness of Gulen, allowing his followers to take up careers in the police and judiciary and even the army, helping to Islamise the institution’s secular ideology. This Gulen generation has now reached senior levels, which explains why the plotters of last week’s failed coup may well have included many Gulenists.

Latif Erdogan believes that the Gulen movement’s work alongside the AKP was always a marriage of convenience. Hizmet represented “social Islam,” while the AKP was for “political Islam”.

Erdogan now agrees with the Turkish president in accusing the Gulenists of having developed ambitions to use their network to infiltrate and take over the state, but not through transparency and elections.

“I agree that it’s a parallel state. At the beginning, our goal was to educate people in religion and morality, but the movement went political when it got bigger. Gulen changed and turned to politics and wanted to be a leader who can rule Turkey. We started on our road together with a spiritual message, but now it’s only secular. He should go back to it,” he told me in Istanbul in 2014, in his first interview with a Western correspondent after splitting with Gulen.

Latif Erdogan was a student in Izmir with Gulen. They both admired the teachings of Said Nursi, a Muslim reformer from eastern Turkey who wrote a series of Quranic commentaries called Risale-i Nur and founded a movement called Nur. Nursi, who was later exiled by Ataturk to a remote province, argued that atheism and materialism led inevitably to corruption. Fifteen years after Nursi’s death, Latif Erdogan and Gulen founded their Hizmet movement to set up schools and colleges to instil the highest standards into public life.

Besides the difference between Gulen’s “social Islam” and the AKP’s “political Islam,” there are other contrasts, according to Aykan Erdemir, who was until last year an MP for the Republican party, Turkey’s old Kemalist party, and is now a senior fellow at the US-based Foundation for Defence of Democracies.

“Gulen is not a Muslim Brotherhood-supporting Islamic authoritarian. I would call the Gulenists heirs of Turkish Anatolian Sufi Islam, pious and economically liberal. Gulen himself is unequivocally a pro-European Union and Atlantic person, a free marketeer and a pragmatist on Israel,” he told Middle East Eye in 2014. “Erdogan is at his core a populist reactionary, a state capitalist and a crony capitalist. Although he favours the EU and Atlanticism, it’s only pragmatic. He’s really against them."

Now the Turkish president is coming under intensifying criticism from the EU and the US for his clampdown on all suspected Gulen sympathisers in state institutions and the media. His demand for Gulen’s extradition is also raising tensions with Washington.

Erdogan has also been left suspecting that the US's initial statements appeared to support the coup, until the president rallied the public to defend democracy and the coup collapsed. If his support for Atlanticism was truly only pragmatic, it may well go into reverse now.

Jonathan Steele is a veteran foreign correspondent and author of widely acclaimed studies of international relations. He was the Guardian's bureau chief in Washington in the late 1970s, and its Moscow bureau chief during the collapse of communism. He has written books on Iraq, Afghanistan, Russia, South Africa and Germany, including Defeat: Why America and Britain Lost Iraq (I.B.Tauris 2008) and Ghosts of Afghanistan: the Haunted Battleground (Portobello Books 2011).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Picture: Self-exiled Fetullah Gulen in Pennsylvania, where he has lived since 1999 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.