Why Algeria's independence was a miracle

In his memoirs, Portrait of the Young Man in Red, Lebanese Communist militant Fawwaz Traboulsi recounts “his” independence of Algeria. In 1962, he was living, studying and campaigning in England. The Algerian revolution had been at the heart of his activity, so much so that he was sometimes mistaken for an Algerian, he explains.

Fifty-five years on, this independence seems inevitable. However, a recent dive into the archives of 1962 showed me a different angle

Incidentally, since high school, he had been in love with Djamila Bouhired, the famous moudjahida (fighter). During independence, he welcomed a delegation of Iraqi activists. They had congratulated one another and celebrated Algeria’s birth together as their own victory.

Many others throughout the world - people coming from developing countries, anti-colonialists, anti-imperialists, socialists, pan-Africanists, in America, Asia, all over Africa and even Europe - considered 5 July 1962 and the end of 132 years of French colonisation as a victory.

Fifty-five years later, this independence seems inevitable. At the heart of the great wave of decolonisation that swept the world from Egypt to the Philippines and from India to Angola, Algeria has served as a model, in addition to materially supporting other struggles for freedom.

For a long time, it seemed to me that those who denied the inevitability of this independence practised a form of negationism: they denied that colonies must reach independence no matter what they faced on their path to achieve it.

They revolve around two dates: the signing of a ceasefire agreement in Evian which was enforced in Algeria on 19 March 1962; and the referendum on self-determination provided for in the Evian agreements, which led to Algeria’s effective independence at the beginning of July 1962.

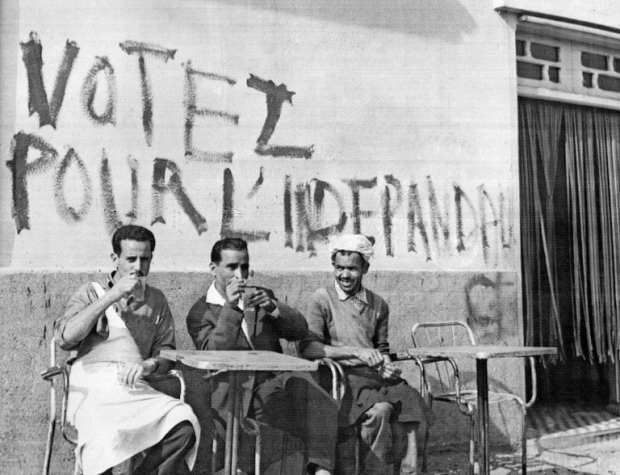

In the referendum held on 1 July, the inhabitants of Algeria answered a massive yes to the question: “Do you want Algeria to become an independent state cooperating with France under the conditions defined by the declaration of 19 March 1962?”

Between those two dates, a transitional period was planned to organise the transfer of authority. This system created the fiction that the process leading to independence could be derailed.

And it opened the way for the Secret Armed Organisation (OAS), a French paramilitary group which sought to prevent Algeria from becoming independent, to develop a European terrorism fuelled by the despair of those who could see their world collapsing.

Moreover, the Evian agreements delayed the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) and the National Liberation Army (ALN) from starting their work until the effective independence.

A peace process that could fail at any time

The agreements created a new authority, the Provisional Executive. Provided with its own police force, the executive came in addition to the surviving maquisards (Algerian resistance fighters) – albeit few in number – who were coming down from the maquis, where they had been fighting during the whole war, and to the French army, which was still there.

We were opening the way to OAS terrorism, while at the same time multiplying the sources of authority. In retrospect, the recipe appears catastrophic

In short, we were opening the way to OAS terrorism, while at the same time multiplying the sources of authority. In retrospect, the recipe appears catastrophic.

The archives I have been able to consult – those of foreign consulates, NGOs and the private Algerian collections – all convey the feeling of an imminent disaster.

Foreign consuls observed the events they were analysing not as a step towards the ineluctable independence, but as a peace process that could fail at any time.

They described with total obliviousness the successive attacks of the OAS, such as the explosion of a booby-trapped car on 2 May in the port of Algiers, after which the OAS snipers hidden in the neighbouring buildings shot dead the wounded and their would-be rescuers.

Every day, they were surprised that the Algerians did not yield to the desire for revenge, and regularly noted the self-discipline of the population. They also indicated that the violence did not come only from the OAS: settlers were attacked, Europeans were kidnapped, while the conflict between the FLN and the supporters of Messali Hadj, the father of Algerian nationalism, intensified during that period.

In the coastal city of Oran, foreign observers described “Muslim neighbourhoods” now surrounded by OAS snipers, regularly showered with mortar fire, whose inhabitants could not restock, tend to the wounded or bury their dead. Those who managed to enter these districts to visit clinics often used the same expression: it was a ghetto.

It was in Oran, during the 5 July celebrations of independence, that the dreaded violence was unleashed.

A long report written in 1963 by the International Committee of the Red Cross describes the electric atmosphere of the packed crowd on 5 July, and the rumour – false but so credible considering the previous weeks – which may have ignited the powder keg: “At around 11 am, Muslim women were seen running home, shouting, ‘OAS! The OAS wants to kill you!’, etc. General panic among them. We then learned that the rumour had been spread that the OAS had killed 200 Muslim women in buses.”

Then the crowd raged. Local leaders, maybe seeking to build last-minute reputations as happens in war, murdered people in the crowd. Some disappeared, never to be found again.

Fighting between Algerians up to Algiers

With the knowledge of the torture, rape, napalm, massacres and forced displacements that have accompanied wars of independence, one cannot help but wonder how 1962 could have been even more violent than previous ones.

Even after July, nobody was completely reassured. Firstly, because the arrival of the border army in the country did not happen without violence, as the maquisards of the wilayas were not ready everywhere to let in those soldiers coming from outside: in September, there were confrontations between Algerians up to Algiers.

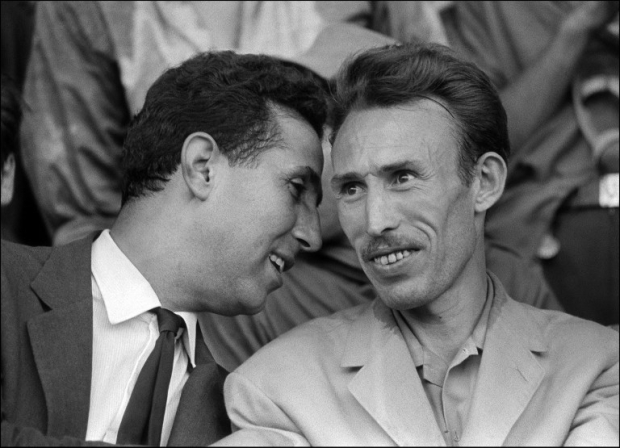

Then, because the arrival in Algeria of the provisional government (GPRA) and the National Liberation Army (ALN) inaugurated an internal struggle for power, that “crisis of the summer of 1962” allowed the army of Houari Boumediene and his champion, Ahmed Ben Bella, to take power.

Finally, and this is undoubtedly the least-known fact, the concern was caused by the risk of a major humanitarian crisis.

With the massive departure of Europeans, unemployment exploded. In agricultural businesses, often deprived of their owners and managers, activity had to resume at all costs to ward off famine on a national scale.

Moreover, about a quarter of the Algerian population had been displaced, the majority living in camps. In March, as many as 300,000 people were living as refugees in Tunisia and Morocco, and wanted to come back.

So close to annihilation

In 1962, people started coming back, sometimes to return to villages rendered uninhabitable by destruction and fields rendered unexploitable by the approximately 12 million anti-personnel mines that the French army placed during the conflict.

International NGOs had already been working in Algeria during the conflict. But in 1962, there were some spectacular interventions: the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) joined forces with the League of Red Cross Societies to repatriate refugees from abroad, in “the largest repatriation operation undertaken with the help of an international organisation since the time of Nansen [the High Commissioner for Refugees from 1920 to 1930], with the exception of the return of displaced people during World War II”, according to UNHCR’s archive.

A 1962 film by Stanley Wright, Comme la pierre est à la pierre, promoted this intervention to raise awareness among donors around the world and avoid national famine.

What averted famine and prevented the collapse of the country was both the extraordinary international solidarity and the spectacular internal mobilisation which made it possible to organise, amid chaos, the start of the new school year in September 1962, and the resumption of agricultural activities to avoid a lost season.That mobilisation was not only based on wartime energy, but also on the years of cultural, sports and partisan mobilisations that had preceded it: part of that discipline and organisation had, for example, been acquired in the scout movement, and in the political parties that existed before the outbreak of the insurrection in 1954.

Independence might not have happened. The Algerian state might not have been born, and we were so close to annihilation

To this must be added the experience of the war, in a way that in 1962, clandestine clinics and food distribution systems were set up in remote areas to ensure survival. Scout groups were also touring the countryside to record the destruction, the number of dead people, and to help searching for the missing.

It was sometimes these young scouts in uniform that served as the only official presence for funerals, where there wasn’t yet an Algerian administration.

Fifty-five years later, this is what strikes me when I look at independence: the idea that so close to the end of the war, everything could still have been lost.

Independence might not have happened. The Algerian state might not have been born, and we were so close to annihilation. This is why I believe Algerian independence is a miracle.

- Malika Rahal is a historian at the Institut d’Histoire du Temps Présent (Paris). She has written extensively on the contemporary history of Algeria, before and after its independence.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: On 23 March 1962, a few days after the signing of the Evian agreement which led to Algeria's independence, leaders of the National Liberation Front participate in a parade of units of the National Liberation Army in Oujda (AFP)

Translated from French (original).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.