Why the West seeks to vilify political Islam

In his preface to the English edition of Francois Burgat’s Understanding Political Islam, author Pascal Menoret tells us the book is “the work of a trespasser. It sums up the breakthroughs of a French scholar who escaped the snug - and often smug - Western enclave to research one of the least understood political movements: Islamic activism.”

Understanding Political Islam, initially published in 2016, is also the work of a passeur - one whose unique, lifelong experiences of travelling, living, working and conducting research across the Middle East and North Africa region enables westerners to understand the world through the subjectivity of the “Islamic Other” (whom Burgat reminds us is not as different from us as we often fantasise Arabs and other Muslims to be).

We are reminded that 'Islamism' is by no means the scary, violent, anti-democratic and dangerous monolith it has for years become in western media and political discourse

One of the many benefits of the book is to offer us an analysis of political Islam that is not tainted or distorted by western prejudices, ideologies, abstractions and Orientalist fantasies that structure the analyses of other Islamologists.

The depth of Burgat’s familiarity with these countries, cultures and peoples stands in sharp contrast to the often abstract or theoretical takes by other Islamologists.

Burgat’s Islamic/Islamist “Other” is situated, historicised and humanised, as opposed to the vilified caricatures we have been served for decades by virtually all western media and politicians as the new enemy - the “Green Threat” that replaced the Communist Red Scare after the fall of the Soviet Union.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Written in elegant prose that is as rich, dense and intelligent as it is clear and accessible, Understanding Political Islam is part autobiography, part travel memoir and part scholarship, where Burgat both synthesises and revisits his prior works on the subject, but also updates them, especially with respect to the Arab Spring and its aftermath.

A true page-turner where the warm, charismatic, personable and generous author is present with us on every page, each chapter takes us on a geographical and analytical journey to one of the various countries where Burgat has worked or studied. The book is a synthesis of a lifetime of thinking, researching and writing on Islamist activism around the world.

The spectrum of political Islam

Without generalising, Burgat effortlessly explains both the diversity and the specificity of the various Islamist movements around the world, France included, as well as their shared commonalities.

We are reminded that “Islamism” is by no means the scary, violent, anti-democratic and dangerous monolith it has for years become in western media and political discourse, where it is now systematically - and wrongly - associated with “fundamentalism” and religious “extremism” at best, and more often terroristic “jihadism”.

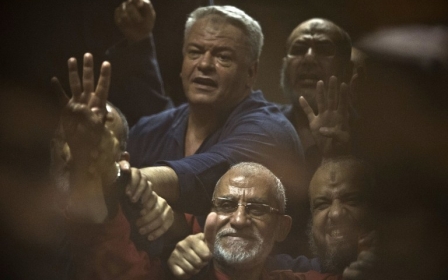

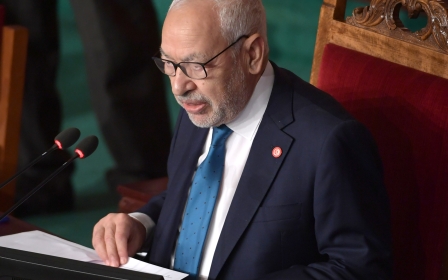

In reality, these groups, movements and parties are often radically different from one another. The spectrum of political Islam comprises both ultra-violent terrorist groups, such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS), but also Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood under the country’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, and other pacifist parties, such as Tunisia’s Ennahda, which has exerted a profoundly democratising and pacifying influence on the political life of that country.

None of those movements are static or immune to change. Far from it: they usually evolve over time, often radically, and sometimes in surprising ways.

The Kepel-Roy-Burgat debate

In the somewhat simplistic typology of mainstream French media, Francois Burgat has been cast as “the third man,” usually after the much better-known political scientists Gilles Kepel and Olivier Roy.

While much has been written on the theoretical rivalry between Kepel’s thesis on the “radicalisation of Islam” versus Roy’s reverse theory on the “Islamisation of radicalism” - with other analysts claiming the two are not incompatible, but complementary - Burgat, the third major figure of French scholarship on Islam (third in terms of the level of media attention he receives, but second to none in terms of analytical power) has rejected both.

Instead, Burgat champions a qualitatively different explanation of Islamism and jihadism. Its starting point is western imperialism, the legacy of colonialism and neocolonialism, and the continuing racism and discrimination of European societies.

In France, the media attention given to Islamologists is primarily determined by whether they fit within the group-think and dominant narrative about “Islamism” - in other words, whether they contribute to that “green scare”. Kepel does, while Burgat does not.

If Kepel and his many disciples highlight the religious, scriptural-theological and ideological dimensions of “religious extremism” (including the non-violent type), and if Roy and others emphasise its psychological and even psychiatric aspects, Burgat re-contextualises, re-historicises, and above all re-politicises Islamism and jihadism, without assuming that the former leads naturally to the latter in “conveyor belt theory” fashion.

Searching for the root causes

For Burgat, both Kepel, who “ascribes a decisive role to the influence of religious doctrine on society,” and Roy, who tries to explain Islamism and jihadism through paradigms such as nihilism, the “death drive” or jihadis as “small-time crooks,” confuse the symptoms for the causes.

Their theories are like “trees that hide the political forest” and misleadingly replace the fundamentally political root causes with religious, ideological, psychological or psychosocial ones.

It is crucial that we stop misunderstanding the phenomenon of the rise and spread of Islamism - so that one day, hopefully, the West can finally develop more rational, mutually beneficial relations with Islam

By excluding the colonial and neocolonial political and historical backgrounds of these phenomena, including western domination of the Muslim “other” through violence far greater than jihadism itself; and by refusing to take into account the enormous responsibilities of non-Muslim actors, such as western governments, and their usually despotic Arab allies in the making of jihadist violence; such disingenuous explanations are also, for Burgat, complicit with French or US nationalist and imperialist neoconservatism.

Analytically and politically, they obfuscate the real drivers, along with the fundamentally political, reactive and oppositional nature of Islamism and jihadism.

For Burgat, Islamism and jihadism do not signal a “return of religion” or a “revenge of God,” but a return to centre stage of the (still-dominated) Global South in the international geopolitical arena, but also at the domestic level.

Retaliatory terrorism

Far from the psychosocial or religious and doctrinal “spasms” described by Kepel, Roy or Abdelwahab Meddeb in his equally ubiquitous Malady of Islam, Islamism and jihadism are foremost mass protests by self-conscious political, often revolutionary actors.

They have everything to do with “post-colonial suffering, youth identification with the Palestinian cause, rejection of western intervention in the Middle East, or exclusion from a racist and Islamophobic France, relations of domination endured by the Muslim component of the population... and the policies of our governments”.

Jihadism thus constitutes a “counter-violence” - a logical outcome of the fact that all “the most ordinary political conditions for extreme violence have been brought together,” mostly by western states and Arab regimes.

There is therefore no need to invoke as root causes a “contamination of Islam,” an alleged malady of Salafism, or other religious, theological, psychosocial or even sexual pathologies. With or without those, the toxic political and geostrategic terrain upon which groups such as al-Qaeda and IS have emerged remains bound to generate reactions of a similar, sometimes violent nature.

To take an obvious example, Iraq under US military occupation did not need to get “Islamised” for armed resistance to inevitably occur. Yet, the ideological function of abstract theories, such as those of Kepel and Roy, is to deny or “conjure away the various effects of the persistence of North/South domination, to discredit the protests of the dominated,” and to maintain the illusion that “their bombs have nothing to do with ours”.

Politically incorrect truths

In sharp contrast, Burgat has tirelessly repeated politically incorrect truths that no one wants to hear, including “that the precondition of the long-awaited democratic transitions is not excluding Islamists from the political sphere. Much less is it hoping that they disappear. The solution is integrating them in the political sphere.”

He notes that the “Islamic reference point” of these movements is in no way “a dogmatic, intangible dead-end divorced from history or impervious to change,” and that there will be no end to terrorism until western states and societies recognise and address their own fundamental responsibilities in the creation of such Frankenstein monsters as al-Qaeda and IS.

They must start by ending their “unwavering support for regimes like that of [President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi] in Egypt; for anti-religious elites marginalised in their own societies; or even for our Israeli ally”. Such indefensible policies, he notes, serve only to “exacerbate the radical, reactive threat these policies are precisely supposed to preserve us from”.

Alas, so far, such healthy recommendations have fallen on deaf ears.

Burgat insists that far more than theoretical disagreements are at stake in the proper understanding of political Islam. The question is which representation of the “Muslim Other” will dominate the public sphere, which affects how we relate to other countries and domestic Muslim populations.

That is why it is crucial that we stop misunderstanding the phenomenon of the rise and spread of Islamism - so that one day, hopefully, the West can finally develop more rational, mutually beneficial relations with Islam and its more than 1.5 billion believers.

Challenging western imperialism

So far, it has been unable to do so. Instead, it has opted for hostility towards, and even eradication of, anything labelled “Islamist” - a toxic and counterproductive policy that is not so much due to the alleged “threat to peace and freedom” but to the fact that Islamism is a powerful, transnational political movement that for decades has openly challenged western imperialist and neo-imperialist hegemony and the sacred cow of “secularism”.

So, what exactly is “Islamism”? In Burgat’s analysis, and again contrary to group-think, it “is less the result of an ideology than the production of new political identities from one’s own ground”. Similarly, the Global South is “a region whose specificity is less its religion or culture than its position right outside the West’s bloody borders”.

Islamism seeks to organise the resistance to both the ongoing western push for hegemony, and to corrupt, co-opted native and national elites

Islamism is the adoption of an “Islamic religious lexicon against colonial oppression and post-colonial modernism,” by which newly independent countries sought to modernise along European lines.

It signals a fundamentally political (as opposed to ideological or religious) and anti-colonialist “turn towards speaking Muslim” - an effort to forge an “indigenous” and “authentic” social and political vocabulary that would be imposed neither from the outside by former colonial powers, nor from the inside by post-independence westernised regimes, nor from above by elites and puppet regimes serving the West.

Islamism seeks to organise the resistance to both the ongoing western push for hegemony and to corrupt, co-opted native and national elites.

A fundamentally reactive and oppositional political movement - and furthermore a major one that Burgat correctly predicted would not disappear, but rather remain an essential and major part of the political cultures of these countries - Islamism is essentially a continuation of the long historical fight for independence from western domination. It is “the extension of the dynamic that successfully fought for independence”.

'The new voice of the South'

Islamism, in all its variants, is indeed “the new voice of the South” - one that is not so much produced by “Islam” as by the history suffered by Muslims at the hands of both foreign colonial states and authoritarian Arab states. In Burgat’s reading, it historically represents the third stage of decolonisation, pursuing the anti-imperialist struggle for independence of now-discredited and ossified nationalist movements, such as Algeria’s National Liberation Front.

In addition to pursuing political and economic independence, or at least distancing from the West, Islamism is now also “starting to reconquer, often successfully, the ideological territory once lost to the North”.

At its core, and regardless of the various forms it takes - whether admirably democratic like Ennahda, or violently terroristic like al-Qaeda - Islamism is the continuation of the South’s long process of self-emancipation from the North. As such, it threatens western imperialist domination, influence and control over these countries, peoples and cultures.

It is therefore not surprising that the West vilifies and seeks to eradicate even the most perfectly democratic and peaceful expressions of Islamism, given that they, too, announce the end of the era of unchallenged European and American hegemony.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.