Why Yemenis are still joining al-Qaeda

On the night of the 18th of October 2012, Abdulmajeed Al-Hasni arrived home after spending four years in prison. Abdulmajeed was only 16 when he was taken from the streets of Sanaa by the Yemeni intelligence – the National Security Bureau (NSB).

A week after his return, the then 20 year old man spent a week with his parents in Sanaa before running away to join al-Qaeda. On 22nd January 2013, Abdulmajeed had died; killed in a drone strike in Al-Jawf, east of Sanaa. His eldest brother Bandar met the same fate, just the day before. When a drone strike hit his vehicle in the neighboring province of Marib.

They was not their family’s only loss. In six months three of the Al-Hasni family’s sons died – Abdulmajeed, the 24 year old Abdullah and the 31 year old Bandar.

The story began in 2005, when Bandar was arrested by the NSB on terrorism related charges. He was accused of being a member of a cell that was plotting to attack US facilities in Yemen.

The NSB had just been formed as a result of a security pact between Yemen and the United States. Ali Abdullah Saleh – the former president – appointed his nephew Ammar as the head of the NSB, and the newly formed bureau was quickly taking over the role of the old established intelligence agency.

The court acquitted Bandar after he spent three years in prison. According to his family those three years were years of intimidation and humiliation by the Yemeni intelligence. The NSB used to conduct night raids and threaten the family, including Bandar’s younger brothers, Abdullah and Abdulmajeed.

The intimidation and harassment of former detainees was a systematic policy by the Yemeni intelligence. Since its establishment, NSB officers harassed ex-detainees in their personal lives. A number of former detainees reported that NSB officers would threaten their employers once they found a job, and their families would be subject to continuous interrogation. Al-Hasni’s family were no different.

In August 2009, Abdulmajeed, who was working with a Yemeni businessman as his personal assistant, was kidnapped by NSB officers along with his employer. He was 16 at the time, and was working during the summer school vacation to earn some money. His employer was released, but Abdulmajeed remained in prison.

“When I used to go to visit him in prison, I found out that I’m not alone,” Abdulmajeed’s mother said. “At the prison gates, you would see a lot of mothers visiting their fourteen and fifteen year old sons,” she added.

Those young boys are on the frontlines of what is known today as al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Many of them were introduced to al-Qaeda members inside those prison walls.

Bandar was kidnapped a few months after his brother Abdulmajeed, and was taken blind folded to the Yemeni intelligence prison before he was released. Abdulmajeed was never charged, but was taken as a hostage in exchange for his brother Abdullah, who joined al-Qaeda that the same year.

Bandar tried numerous times to get Abdulmajeed released, and tried to convince the Yemeni intelligence that Abdulmajeed had nothing to do with the decisions and actions of Abdullah, but it was to no use.

The Arab Spring and al-Qaeda

As the protests were filling the streets of Sanaa in 2011, Bandar, like many Yemenis, decided to join the protests to topple what many believed to be an authoritarian, oppressive regime.

In Yemen, like in Egypt, Syria and Libya, jihadist movements were present in the revolutions, believing them to be a chance to rebel against what they regarded as corrupt and puppet regimes. This was added to the fact that many of them have had first-hand experience with the security and intelligence system of those regimes.

Jihadists partially agreed to the demands of toppling the regimes but didn’t agree on following peaceful methods. The use of violence to achieve justice is appealing to many youth in the Arab world today. Many felt that they had not been given anything by the national states created in the 1950s and 1960s, and they felt no particular allegiance to them. Years of injustice, failure and oppression paved the road towards mass revolutions in 2011, which later descended into civil wars.

Similarly to what Assad did in Syria, and in order to tinge the movement with extremism, the Yemeni intelligence unleashed hundreds of detainees, as well as chasing former detainees and increasingly harassing them and their families.

Bandar’s sister said that the NSB told her brother in 2011 that they could not guarantee his safety anymore and that his only option is to join his former prison mates in Abyan, South Yemen. In April 2012, al-Qaeda announced that they had taken control of Abyan. Bandar was not alone - many prisoners who were captured after the government took control of Abyan in 2012 told a similar story of being ordered to go to Abyan.

According to his family, Bandar didn’t fight with al-Qaeda, and by mid-2012 he contacted the Yemeni intelligence to request his return to his family. Despite his desperate attempts, the Yemeni intelligence refused his requests.

After the revolution

In July 2012, the Al-Hasni family received the news of the death of Abdullah, who died in armed confrontation between al-Qaeda and the Yemeni army in Abyan. Abdullah was the first to die in a conflict that his family didn’t decide to be part of.

Abdulmajeed was finally released in October 2012, but, according to his mother, four years in prison changed him. He was filled with anger and a sense of revenge. “He changed, he was so angry all the time, remembering how he was tortured in prison,” his sister said. Abdulmajeed wasn’t even religious according to one of his prison mates.

Abdulmajeed spent one week with his family before running away to join the same people he knew in prison.

Only a few months passed before the family were told the tragic news.

On 21 January 2013, Bandar died in a drone strike in Marib. He had notified his family a few days earlier that he was trying to convince the Yemeni intelligence to return back to Sanaa. A day later, his brother Abdulmajeed would face the same fate.

The Al-Hasni family is a regular Yemeni family. They wouldn’t strike you as an extremely religious family but the conditions they lived through made al-Qaeda part of their life.

NSB had and still have tens of informants working within the layers of al-Qaeda. In a meeting between the National Dialogue members and the NSB in 2013, NSB deputy Mohammed Al-Hadher was proudly stating, “We are the only security agency that have successfully infiltrated Al-Qaeda.” What the NSB considers infiltration, for many families like Al-Hasni’s, it was recruiting and pushing their sons to join al-Qaeda.

When the Houthi rebels took over Sanaa in September 2014, the NSB was the only government institution that remained unoccupied by the Houthis. It continued functioning as normal even after the civil war broke in the country.

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula however benefited from the current conflict and extended its reach to many provinces. The NSB policy of “feeding the beast in order to control it” have failed, and al-Qaeda is now largely going out of control.

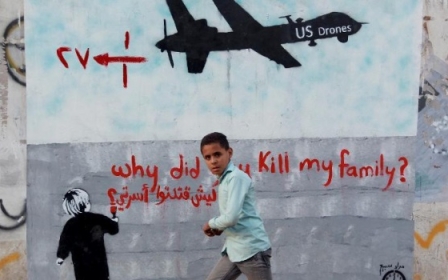

Although al-Qaeda lost its top leaders, al-Qaeda as an idea remained. Young people convinced now more than ever that the only tool to achieve justice from their persecutors is using violence.

- Baraa Shiban is a Yemeni human rights activist. He is the Yemen project co-ordinator for the human rights organisation Reprieve.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

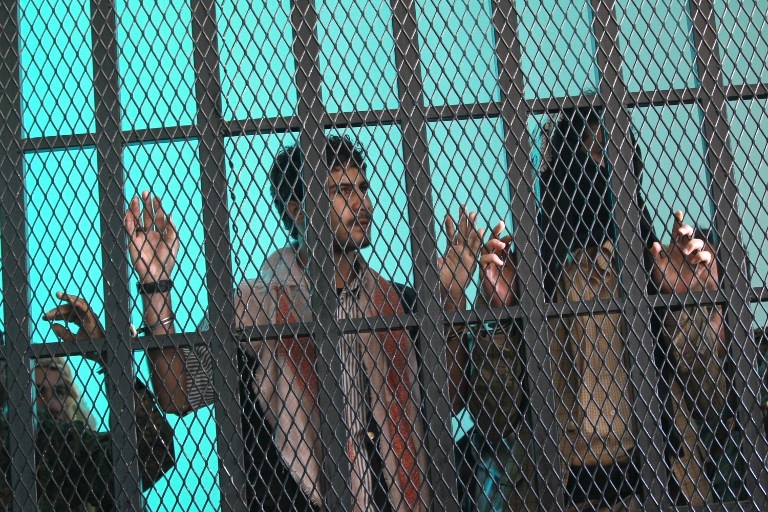

Photo: Suspected al-Qaeda militants stand behind bars during a hearing at the appeals court in the Yemeni capital Sanaa on 3 February, 2015 (AFP).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.