Will the new Sudan follow Egypt's authoritarian path?

Sudan’s interim prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, was pictured a short while after the failed attempt on his life on 9 March with a beaming smile, sitting behind his desk in Khartoum.

The photographer made sure to capture the television screen in his office in the same frame, carrying news of the assassination attempt from an Arabic channel. In his landmark uplifting style, Hamdok issued a statement saying: “What happened will not stop the march of change and will only be an additional splash in the high wave of the revolution.”

Expensive political choice

Government spokesman Faisal Mohamed Saleh immediately labelled the attempt a “terrorist attack”. Two days later, on 11 March, Saleh announced the arrest of several suspects, including foreigners, and confirmed the arrival of a team of US security experts to join the investigation effort.

Saleh willingly adopted the narrative of the US “war on terror”, saying that the government requested the aid of the FBI “due to its experience and the modern technologies it has, especially as Sudan is a country that has no experience in dealing with this kind of incident”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Sudan's new rulers are evidently keen to prove their worth in the US security architecture, for the immediate purpose of slipping off the US state sponsor of terrorism list

Saleh recalled events in February, when Sudanese security forces announced the arrest of members of a “terrorist cell” headed by an Egyptian national who allegedly confessed his ties to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Sudanese authorities claimed that members of the cell who carried forged Syrian passports had received training in explosives and were plotting a series of assassinations targeting Sudanese officials tasked with dismantling institutions of the deposed regime of former President Omar al-Bashir.

Interestingly, the lot of Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood members who sought shelter in Sudan after the July 2013 Egyptian coup, during Bashir’s rule, was not much better. They were traded for favours from Egypt’s dictator.

Bashir’s regime had laboured strenuously to shed its earlier record of Islamist adventures, foremost the 1995 botched attempt on the life of Egyptian autocrat Hosni Mubarak in Addis Ababa, and relocate itself in the terrain of US subservience.

It happily advanced cooperation with US intelligence in the aftermath of 9/11, but the reputation of Sudan’s security cabal made open normalisation of ties an expensive political choice domestically for successive US administrations. Nevertheless, cooperation continued, and the CIA was pleased with the performance of its Sudanese clients under Bashir right up to the end of his rule.

Surprise meeting

Sudan’s new rulers are evidently keen to prove their worth in the US security architecture, for the immediate purpose of slipping off the US state sponsor of terrorism list and to strategically align with their powerful Arab Gulf patrons, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, in the regional political order.

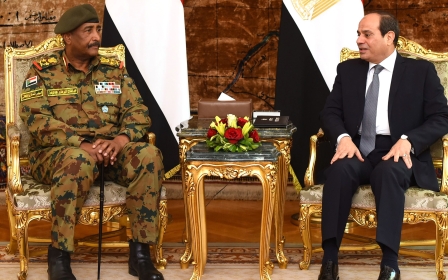

Sudanese leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan stated as much when arguing his case for normalisation of ties with the Israeli occupation after his surprise meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Uganda’s Entebbe in early February. The meeting was allegedly arranged by Abu Dhabi with the involvement of Riyadh and Cairo.

The facts of the attempt on Hamdok’s life remain murky. A bomb planted in a parked car exploded as his convoy passed by in the Kober district of Khartoum North, and a volley of bullets was heard. Accounts vary, however, with some claiming that a projectile was fired against the convoy from a high building.

The political consequences, if not benefits, of the attempt unfolded in quick succession. On the same day, Egypt’s security chief, Abbas Kamel, was received by Sudan’s military rulers, and held separate meetings with Burhan and his deputy, Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, leader of the Rapid Support Forces militia.

A few days later, Dagolo flew to Egypt, despite a flight ban in relation to the coronavirus pandemic, for meetings with Egyptian officials, including President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, partially to smooth out a serious disagreement over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam; Sudan had opted out of an Arab League resolution supporting Cairo’s position in the dispute with Addis Ababa, drawing official Egyptian disdain.

Dictionary of repression

Domestically, the assassination attempt drew the civilians of the tenuous transitional authority closer to their military allies. A joint meeting of the cabinet, the sovereignty council and the leadership organ of the Forces of Freedom and Change resolved to establish a new internal security organ separate from the General Intelligence Service, with the mandate of tracking, monitoring and pre-empting the actions of members of terrorist organisations or any organisation with objectives opposed to the 2019 revolution.

This generous formulation is borrowed directly from the dictionary of repression, and I assume will come to haunt the very women and men who toppled Bashir the dictator. Indeed, Sudan’s new rulers have struggled to counter or absorb the independent and multiple organisational forms of Sudan’s protest movement, foremost the ubiquitous resistance committees.

The new security organ, with designs likely to be fashioned following the Egyptian example, will probably serve the dual function of appropriation and repression through incorporation of willing recruits into the new security apparatus, and the subjugation of others who defy the will of the state.

Meanwhile, Hamdok, it must be said, risks deteriorating into the mantle of Egypt’s Adly Mansour, the former acting president and perfect placeholder who gave cover to Sisi's 2013 coup.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.