Can South Sudan's men of war lead the country to peace?

South Sudanese artist James Aguer Garang has invited us into his sparsely furnished studio. Propped against the wall is his most famous painting.

On the right side of the canvas is the nation envisaged at the time of independence in July 2011. Blue sky. Cattle grazing in lush grass. A father and daughter walking hand in hand.

The left side of the canvas represents the reality of war: rape, destruction and death. A child tries to suckle milk from its dead mother’s breast. Villagers flee from their burning huts as soldiers advance.

“This is the story of our country,” says Garang, a gentle and serious man in his 40s. With a pen in his shirt pocket and wearing a dark suit, he dresses more like an accountant than an artist.

The picture is personal for him. Aged nine, Garang was one of a force of 20,000 children enlisted by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army to fight in the second Sudanese War, which lasted from 1983 to 2005.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Told by soldiers he would be going to school, instead he was taught to use a gun. He saw combat in one of the most bloodthirsty conflicts of modern times in which more than two million lives - approaching one quarter of the South Sudanese population - are thought to have been lost.

Garang has a scar above his right eyebrow. “We were running from the enemy,” he explains. “We had to cross a river. They were shooting at us so I dived down deep to escape the bullets and hit my head on a rock.”

“Every day when I look in the mirror, I am reminded of that time.”

After five years Garang deserted, making a five-month journey on foot through the Ethiopian bush before reaching a refugee camp in Kenya.

There he learned to paint, following in the footsteps of his father who had been a traditional craftsman, carving sculptures out of wood and cow horn.

Today, Garang is not only one of South Sudan’s most well-known painters, but also uses art to provide trauma therapy to children and adults affected by war.

“There is no worse disease than trauma in South Sudan,” he says. “The first thing trauma attacks is your thinking brain. You don’t concentrate. You don’t remember things. You have issues in your personal relationships with people.

“In South Sudan, fighting is the normality. There are no apologies. That’s the life of a traumatised community.”

South Sudan has been in a state of conflict for much of the period since Britain gave Sudan its independence in 1956, ignoring repeated warnings from local people and knowledgeable colonial officials that the south was too distant and underdeveloped to submit to rule from Khartoum.

The first Sudanese rebellion broke out in 1963, and persisted for a decade. An uneasy ceasefire held until 1982 when war broke out again. It lasted 21 years until a peace deal was struck in January 2005.

South Sudan secured independence after a referendum in 2011 only for civil war to erupt two years later.

Most have suffered the loss of family members. Far too often their entire family. Many have themselves committed atrocities. Millions have known the terror of fleeing their homes. There are more than one million South Sudanese refugees in neighbouring Uganda alone.

James Aguer Garang's organisation tries to confront this spiral of violence with street art projects for young people. It is called Ana Taban - Arabic for “I am tired”.

“We in South Sudan are tired of war,” says Garang.

“We need to come to our senses, to prevent ourselves from being victims and aggressors. But it’s hard to change by yourself. That’s why we need programmes for people who cannot stop aggression.”

Garang firmly believes there is the potential for change. “From trauma there can be reconciliation,” he insists.

Scorpions in a bottle

An attempt at reconciliation is under way. Fifteen minutes' walk from Garang’s office is a dusty road beside which men sit in plastic chairs drinking tea.

On one side is the national football stadium, separated from the street by a corrugated iron fence. Opposite is a row of modern hotels. This year these have been home to rebel leaders, warlords, diplomats, government officials and international powerbrokers.

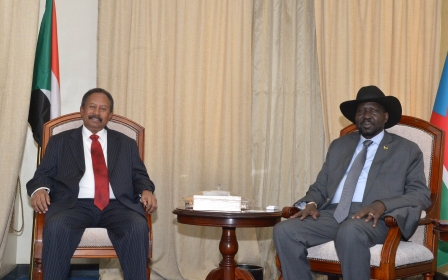

They are there to negotiate a peace settlement between South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir and rival Riek Machar. Peace depends on the two men forming a transitional unity government by an agreed deadline of 22 February.

Machar and Kiir started out as comrades nearly 40 years ago in the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, the main rebel opposition to Khartoum, led by legendary guerilla fighter and national hero John Garang.

They became enemies in 1991 when Machar mounted a failed coup against John Garang, with the support of Khartoum. Kiir remained loyal and was named Garang’s successor after he died in a helicopter crash in 2005.

The pair reunited in 2011 when Kiir became president and Machar vice president of the newly created Republic of South Sudan. The partnership failed - think scorpions in a bottle - and in 2013 South Sudan again descended into war.

Only this time the war was not between the north and the south. The South Sudanese were fighting each other.

Machar was reinstated as vice president in 2016 in a failed attempt to broker a peace. After three months, fighting broke out between the two men’s forces. Machar fled the capital, pursued by Kiir's forces. There is still no consensus on who started the fighting. All too quickly, the renewed political struggle mutated into a barbarous conflict between the nation’s two largest tribes ("tribe" is the term used by the South Sudanese), Kiir's Dinka and Machar’s Nuer.

Soon the southern Equatoria region, which largely avoided conflict in 2013, was dragged into the fighting. Before long the entire country was at war. Many feared South Sudan would descend into the genocidal violence that overtook Rwanda in 1994.

Under international pressure, South Sudan somehow pulled itself back from the brink. By December 2017 Machar and Kiir had agreed to a ceasefire, and have been dragged back to the negotiating table. Many regard today as the most hopeful moment in South Sudan’s short history.

Negotiations are being led by a trade group of eight east African countries known as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), which was responsible for the Comprehensive Peace Agreement signed in 2005.

Support is also being provided by the so-called troika made up of the United States, United Kingdom and Norway. Local and international church leaders, including the Pope and the Archbishop of Canterbury, have played their part.

Every power in the region supports peace. Uganda, (a long-term backer of Kiir) is playing a significant role. Ethiopia, which has often hosted rebel troops, put on the start of the peace talks.

South Africa is pushing for a settlement, which it sees as the perfect start to its term as the new chair of the African Union, a role it assumed in January this year.

Perhaps most significant of all, the ousting of Sudan’s former president Omar Bashir, who waged war against the south for many years, has produced a more positive atmosphere. “The stars are aligned,” one diplomat told us.

The world's youngest country

South Sudan is called the world’s youngest country. The 11 million population is made up of over 60 ethnic groups, none of which are a majority. The largest group, the Dinka, make up around a third of the population. The second largest group, the Nuer, is around half that size.

Some differentiate themselves with facial scars. It is not uncommon to see men with long v-shaped lines etched into their foreheads. Others have parallel lines stretching around to the back of their skull or crosses and stars on their cheeks.

Almost every tribe has its own language. Arabic, from the days of unification with Sudan, is the closest South Sudan has to a national language. English and Swahili are also popular among the millions who sought refuge in Uganda and Kenya.

The breakdown of national unity into tribal disputes and poverty has led to uncontrolled, armed clashes across the country

During the decades of war with Sudan, tribes had a common enemy. After independence, any national identity unravelled almost immediately as South Sudan’s leaders returned to tribal affiliations and lined their own pockets with resources meant to build a country.

South Sudan is the size of France, but where France has more than a million kilometres of tarmac roads, South Sudan has less than 300 - a discrepancy that becomes worse when you consider that South Sudan has had a yearly revenue of more than £1.15bn from oil alone since 2005.

A lack of formal institutions at the time of independence made theft easy. The vast majority of South Sudan’s population are farmers or cattle keepers with no formal education.

Cows have for centuries been the centre of the economy and culture. Little has changed. In villages cows remain the preferred currency. In Juba, the most powerful people in South Sudan pay for dowries, or hide stolen money, in vast herds.

Money for roads, schools and hospitals quickly ended up in the pockets of the new administration, made up of former generals and veterans with no experience of government.

One particularly nefarious example, known as the Dura Saga grain scandal, saw £1.53bn set aside for food storage facilities to protect against famine disappear.

After two consecutive years of flooding in much of the country, famine is again expected in much of South Sudan. There is still no infrastructure to protect the starving.

In 2012, President Kiir - a major beneficiary himself of looting the public purse - issued a half-hearted public appeal to 75 top officials to return over £3bn.

Unsurprisingly, nothing was returned. Corruption is still widespread. A report published in September 2019, released by the Sentry, an investigative team in the nonprofit group Enough Project, detailed an international network of actors assisting local kleptocrats in the theft of billions, from “Chinese-Malaysian oil giants and British tycoons to networks of traders from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya and Uganda”.

The result for the people of South Sudan has been famine and war. The breakdown of national unity into tribal disputes and poverty has led to uncontrolled, armed clashes across the country.

'You don't know why they want to kill you'

It takes at least two days to drive the 400 miles north from Juba in the south to Wau, the country’s second largest city. There are no tarmacked roads, and roadblocks manned by militias. Robbers line the route. To avoid trouble, we drove in from the north.

We reached a school with no windows, no doors, no benches, just a blackboard. Teachers get paid 3,000 Sudanese pounds, less than £10 sterling, a month. Even that money seldom gets paid.

One tells us: “We are used to going six months without salary. How do you think we can eat? I cannot feed my children.”

Philip Nyok, principal of a nearby teacher training college, says that peace “will change so many things. People will be able to go back to their areas. They will cultivate their land. They will get more income”.

“You cannot get away five miles from here because you will be killed by unknown gunmen,” he says. “You don’t even know why they want to kill you. That is why you cannot get out of town and cultivate your crops.”

Despite the heat, Nyok is dressed in a smart grey suit, a jumper and tie. Like James Aguer Garang, he tells us “we are tired of war”.

“South Sudan needs strong people. Independent people. Hard-working people who can support themselves,” he continues.

“They won’t need support if there is peace. But with insecurity there are no jobs, no food, no shelter.”

Despite the current situation, Nyok has ambitious plans. He drives us out of the town to show us. At once the landscape opens out, dry bush spreading for miles on either side of the increasingly worn-away track. Small trees provide occasional patches of shade.

We pass a man collecting firewood, sweat dripping from his face. After 15 minutes we reach 50 hectares of virgin land that Nyok has set aside to turn his college into a university campus.

There is no fence or sign to mark out the site, nothing to distinguish it from the miles of bush surrounding it. There is still everything to be done. It is men like like Nyok who are determined to deliver the future South Sudan dreamed of at independence nine years ago, if their leaders will let them.

'Too dangerous to go home'

A few miles from Nyok’s campus, at a camp for internally displaced persons on the east bank of the Jur river, we found Adom, a mother of eight.

Sitting cross-legged outside her tent, children playing at her feet, she said: “I was born in the conflict. I was married in the conflict. And now I am growing old in the conflict.

“I miss my house. I miss it so much. But everything has been destroyed.”

'I was born in the conflict. I was married in the conflict. And now I am growing old in the conflict'

- Adom, mother of eight

Adero, a mother of seven, recalled: “My nephew was shot dead while we were sharing a plate of food. We just ran. I can’t go home until security comes.

“When I hear the opposition and the government agree, I can then think about returning home. I’m not just missing my village. I am crying my heart out. But it is still too dangerous to go home.”

Another lady, Asunta, arrived in the camp last March, having walked three days after her village came under attack. She said that “if they form a unity government, I will go back”.

Most of the people we spoke to were members of the Luo tribe, who had fled from Dinka raiders. The collapse of order in South Sudan has enabled indiscriminate warfare between different tribes.

Disagreements which used to be settled with low-level violence and regulated by elders are now settled with machine guns and RPGs, all too easy to obtain in a time of civil war.

The South Sudanese tragedy is only in part fought between the rival armies of Kiir and Machar. The horror of their war has unleashed a kaleidoscope of local conflicts which cannot be resolved without national unity.

'We are all one'

Back in Juba, negotiators face two sticking points. The first is the sensitive matter of merging Machar and Kiir’s armies into a national institution. This is going better than expected.

Beside the swimming pool of a Juba hotel we met Colonel Lam Paul Gabriel, spokesman for Machar’s opposition army. Gabriel told us there had been no major clashes since November 2018, and that huge strides had been made in merging the two armies in training centres set up across the country: "The troops are really happy together, sleeping together, celebrating together, eating together."

He added that troops enthusiastically sing “We are all one” at the training centres. Up to 40,000 members of the new national force will soon be deployed at border checkpoints and on policing duties.

The colonel insisted that no decision had yet been made whether opposition chief of staff Lt General Gatwech Dual or General Gabriel Jok Riak, head of Kiir’s army, would be in charge.

The same positive message comes from the government side, though one diplomat observer of the talks is sceptical.

“Are they sending core combatants to the camps?” he asked. “Or are both sides recruiting people to go to the camps while leaving hardened troops in key defensive positions?”

In any case, the unification of the army still holds great symbolic value. It is an institution that transcends tribal loyalties, a rare thing in South Sudan.

If peace is to hold, the formation of a new national identity will be key. In a society where most positions of authority are held by former SPLA generals, the army is an obvious place to begin this process.

The second issue is the number of South Sudanese states. What sounds like an administrative detail is deeply political. At independence in 2011, South Sudan was split into 10 states. Since then, Kiir has twice increased the number - to 25 in 2015 and then to the current 32 in 2017.

Critics insist that Kiir’s redrawing of boundaries is designed to gerrymander Dinka majorities in resource-rich areas, especially those with oil. More importantly, those same majorities will ensure Kiir wins the national elections slated to take place in three years' time.

Machar has understandably refused to accept the current 32 states. He has also rejected a suggestion from South African mediators that the issue is put to an international arbitration committee.

Machar has offered a return to the 24 states recognised under the British administration, with Juba being made an additional neutral state. It’s one of the more attractive options, due to having historical boundaries to work from. However, Kiir is refusing to compromise.

This failure to reach an agreement reveals more than bad faith. Machar and Kiir are terrified of each other.

After years of bitter fighting, both fear for their lives. Kiir has refused to provide Machar (who is said to have British citizenship) with a South Sudanese passport.

Machar, who lives in Khartoum, travels to Juba in the military jet of Sudan’s General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemeti, a senior member of Sudan's transitional government and commander of the country's Rapid Support Forces, formed from elements of the Janjaweed militia accused of massacres in Darfur.

He never stays in the city without his Sudanese protector. And whenever the pair are in the city, trucks full of elite presidential guards - known as the Tiger Battalion, named after Kiir’s rebel codename - are stationed outside their hotel.

Bullet holes in the walls

The guards outside Kiir's presidential palace in the centre of Juba look more relaxed. They wear stylish military fatigues and red berets. They sport dark glasses and smoke cigarettes. But the walls behind them are pockmarked with bullet holes, legacy of the gunfight between Kiir's and Machar's troops last time they tried to form a government in 2016.

Goats graze in front of plaques announcing South Sudan's slogan “Justice, Liberty, Prosperity”.

In Kiir's private office we meet the president’s secretary, who tells us she used to campaign against gender violence. Kiir enters wearing his trademark stetson hat, presented to him by US President George W Bush on a visit to the White House almost 15 years ago. He has rarely been seen without it since.

The president walks slowly, and his conversation is interrupted by long, pregnant pauses. Kiir maintains he is “hopeful” that a unity government can be formed this month.

At the same time, suspicion of Machar can be heard in much of what he says: “Riek is not convinced about the agreement because the agreement does not make him president. He has been threatening to go back to war.”

“If he captures the centre of power, if he controls Juba even for a day, he will claim he is president,” the president continues. “Even if he is here [in the room] for 24 hours, his ambition is completed.”

Who will be commander in chief? Kiir replies: “Of course, it will be someone from our side,” contradicting the earlier briefing from Machar’s military spokesman.

“We all want peace except Riek Machar,” adds the president. We reply that Machar also says he wants peace. “There is a difference between what you say and what you have in your heart.”

We observe that making peace requires forgiveness. Kiir replies: “I’m a very forgiving person. In my life I don’t seek revenge. If a person does me wrong on many occasions, I have no problem.”

“Last time the peace did not hold because Machar was not convinced. If we form a government now and Riek accepts the role of first vice president, it will hold. If this government succeeds the past will be forgotten.”

Kiir pauses, then mentions the bullet holes outside the presidential palace: “You have seen the walls. The bullets. I did not close them. I want to remind him. When he comes in together we will plaster the walls. We will repair them. Paint them.”

History is full of examples of men of violence who have given up arms and led the way to lasting peace. But are Machar and Kiir capable of the necessary generosity of spirit and moral heroism? With the 22 February deadline nearing and no compromise yet reached, that question is yet to be answered.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.