Egypt takes its politics of denial to new levels

Since the July 2013 military coup that ousted Egypt’s first-ever freely elected president, Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s new government has been among the world’s worst violators of human rights. Atrocities include mass killings, arbitrary arrests, mass death sentences, forced disappearances, forced evictions and widespread torture, among other things.

Given the scope of the human rights violations, it is unsurprising that the current regime, led by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, finds itself in an international image crisis. Journalists, scholars, human rights groups, and foreign diplomats have taken turns censuring the Egyptian administration over its combination of draconian legislation, atypical judicial behaviour and brute force.

Under the circumstances, Egypt’s rulers wouldn’t have been able to completely avoid a public relations crisis. However, more reasonable responses to some of the violations would have put the government in a better position to counter at least some of the international criticism. Rather than own up to mistakes and work toward corrective action, the government has often denied or downplayed violations. Arguably, Egypt has taken the politics of denial to new levels.

For instance, the Egyptian judiciary has been under fire recently for sentencing three-year old Ahmed Karni to life in prison for a host of violent crimes the toddler is alleged to have committed when he was a 17-month-old baby. Of course, the charges, conviction and sentencing are all absurd and create a public relations nightmare in and of themselves.

However, the government’s response has intensified the public relations problem. Instead of apologising for the mistake, official Interior Minister spokesperson Abu Bakr Abdelkareem downplayed the incident on national television on Friday evening. Although he said Karni and his father were safe to go home, Abdelkareem denied documented evidence that police had visited the family home earlier in the day and that the boy’s father had spent four months in jail as part of the case.

Also, news broke Saturday that seven police officers were arrested before a scheduled appearance on a television programme. An Egyptian daily reported that the Interior Ministry made the arrests because it suspected the officers intended to criticise the regime over its handling of Karni’s case.

This month’s sentencing of a toddler follows a 31 October 2015 Russian passenger jet crash in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The New York Times reported that investigations led “most of the world” to conclude that terrorism was the likely cause of the crash, for which ISIS claimed responsibility. The Sisi regime, however, denied that terrorism was the cause of the crash and instead resorted to conspiracy theories. According to the Times, an adviser to the Minister of Tourism said: “Of course we are talking about a [western] conspiracy.”

Police violence

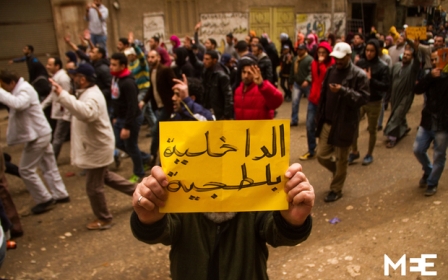

The damage done to Egypt’s image by the recent sentencing of a toddler and the Russian plane crash pales in comparison to harm caused by police-perpetrated violence, which has created a series of public relations problems for the Egyptian regime. The government’s reactions to the violence - ranging from blame deflection to outright celebration - have only exacerbated the image crisis.

On 14 August 2013, Egypt’s police committed what is possibly the largest massacre against protesters in modern world history, killing at least 900 protesters over a span of a few hours at two large public squares in Cairo. Rather than investigate police for excessive use of deadly force, Egypt’s government congratulated police for a job well done. In the immediate aftermath of the massacres, media outlets and government officials described police officers as heroes and saviours. Two prominent pro-government television news networks showed heroic footage of Egyptian police while playing theme music for Pirates of the Caribbean and Rocky, respectively. In a sort of salt-in-the-wounds gesture, the government erected a statue honouring police officers at the site of the largest massacre, Rabaa Square. To date, the government has not apologised for the mass killings, nor acknowledged blame.

In May 2015, Egyptian police fatally shot a 31-year old female protester, Shaimaa El-Sabbagh, with birdshot. The tragic images of El-Sabbagh dying in the arms of another protester went viral on internet news sites. Unsurprisingly, global outrage - from human rights groups, journalists and scholars - ensued. In the aftermath of another police-perpetrated fatality, the Egyptian government attempted to deflect blame. The New York Times reported that a spokesperson for the Medical Forensics Authority, Hisham Abdel Hamid, said that El-Sabbagh only died because she was too skinny. Implying that the use of birdshot on an unarmed protester from pointblank range was not necessarily problematic, Abdel Hamid said: “[El-Sabbagh’s] body was like skin over bone, as they say. She was very thin. She did not have any percentage of fat. So the small pellets penetrated very easily.”

Also in May 2015, Egypt executed six young men following a swift, irregular murder trial in a military court. Both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International documented evidence that three of the six men had been arrested and detained (and had hired lawyers) three months before the crimes they were executed for were carried out. Human Rights Monitor, meanwhile, presented evidence that the remaining three men were arrested days before the killings occurred. Following widespread international criticism, Egypt’s Interior Ministry defended both the trial and executions. Responding specifically to a critical statement released by an Egyptian political party, an Interior Ministry spokesperson said criticism of the executions was “impermissible and incorrect”.

Questions also surround Egypt’s official response to the recent torture and murder of an Italian graduate student, Giulio Regeni, who went missing on 25 January 2016 and was found dead in Cairo on 3 February. As Professor Khaled Fahmy has noted, a pair of autopsies performed by Italian and Egyptian medical authorities showed signs of extensive torture, including slit ears, cigarette burn marks, and completely extracted fingernails and toenails. Importantly, the Egyptian autopsy report omitted some of the more grisly torture details.

A letter to the Egyptian government signed by more than 4,000 academics noted that Regeni’s forced disappearance and torture were consistent with the practices of Egypt’s security forces. The letter cited an Amnesty International report documenting the systematic patterns of forced disappearances and torture carried out by Egyptian security forces. Egypt flatly denied suggestions that police may be behind either Regeni’s disappearance, torture or murder. Egypt’s interior minister said, “there are many rumours repeated on pages of newspapers insinuating the security forces might be behind the accident. This is unacceptable. This is not our policy.” Egyptian authorities have promised an investigation, however.

Occasional acknowledgement of police transgressions notwithstanding, the Egyptian government has, for the most part, downplayed and ignored police brutality. Regime responses have led to overwhelmingly critical reportage in international news outlets, and rebuke by a number of important foreign governments, including some otherwise strong allies.

The Egyptian population may be growing tired of what has developed into a consistent pattern of abuse and denial. After a police officer shot a civilian in Egypt last week, protesters surrounded the Cairo Security Directorate, demanding justice and chanting against the Interior Ministry. Also, demonstrations were organised by the Egyptian Medical Syndicate last week after a pair of Egyptian doctors were roughed up by police. The protests were held in spite of a draconian protest law that effectively prohibits demonstrations.

Judicial rulings

The Egyptian government’s responses to a series of absurd mass death sentences - the largest in modern world history - also offer a useful stopping point. In 2014 and 2015, Egypt’s judiciary issued four unprecedented mass death sentences, including one sentence against more than 500 people for the alleged killing of one policeman. Some of those sentenced to death were either already dead or in jail at the times alleged crimes took place, making their guilt an impossibility.

Rather than acknowledge the legitimate criticisms expressed by global human rights groups and diplomats, Badr Abdel Aaty, an official spokesperson for Egypt’s Foreign Ministry, rejected criticism and defended Egypt’s judiciary as free and independent. He said that other countries should not interfere in Egypt’s internal affairs, noting that “absolutely unjust” court rulings are issued regularly in other countries, but Egypt wisely chooses to avoid interfering.

He went on to say that Egyptians should “not attach a great deal of importance” to the critical comments made by human rights groups and Western diplomats, adding that “some Western countries have given us a headache with talk of respecting human rights”. Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry and other government officials also offered up passionate defences of Egypt’s judiciary.

The government has also failed to appropriately acknowledge Egypt’s mass incarceration problem. Human rights groups, journalists and scholars have widely reported that Egypt has arrested more than 40,000 people since the start of its July 2013 crackdown, and, as I’ve explained elsewhere, government press statements corroborate the reported arrest numbers. In spite of the fairly obvious fact of mass arrests, Shoukry recently complained to Foreign Policy that the arrest figures provided by journalists and other observers represent gross exaggerations. He suggested that Egypt has fallen victim to a global propaganda campaign that resembles Nazi propaganda.

In one particularly high-profile case, three Al-Jazeera journalists were convicted in 2014 on terrorism-related charges, with each journalist given a prison sentence ranging from seven-to-10 years. The case was widely condemned in international media and human rights circles, with observers noting gross irregularities in the trial, including the fact that it didn’t appear that there was any evidence that the journalists were doing anything more than reporting on Egyptian politics. Egyptian prosecutors presented bizarre evidence, including photographs of a European family vacation and a documentary about Somalia.

After the verdict, an Egyptian state-owned daily newspaper reported that Egypt’s Foreign Ministry instructed Egyptian embassies abroad to “request urgent meetings with foreign affairs officials” to justify the convictions. Egyptian ambassadors were provided a list of talking points, which included an affirmation of the “independence of Egypt’s judiciary and the rights of free and independent media”. The Foreign Ministry also rejected foreign attempts at “meddling” in internal Egyptian affairs.

Out of touch

The Egyptian government’s responses to human rights violations may be contributing to a sense among Egyptians that their rulers, including Sisi, are out of touch with some relatively primitive realities. Other aspects of Sisi’s rule may also be contributing.

For example, Sisi was recently criticised for rolling out a 2.5-mile long red carpet for his motorcade. Some Egyptian and western media outlets saw the massive red carpet as inconsistent with Egypt’s basic economic condition, which, by all accounts, is dire. Sisi’s prized economic project - the expansion of the Suez Canal - has not generated any increased revenue, and the value of the Egyptian pound has plummeted to an all-time low against the dollar. Moreover, Sisi has instructed Egyptians to limit their consumption and warned of more subsidy cuts, including on clean water.

Earlier, during his presidential campaign, Sisi had suggested that Egyptians were overly demanding, asking Egyptians if they were “going to eat up Egypt”. Seen in light of this larger economic context, a 2.5-mile red carpet motorcade appeared to many to be incongruous.

Additionally, in a recent speech to parliament, Sisi said that Egypt has “laid the foundation of a democratic system”. This statement, too, seemed to fly in the face of reality. At present, Egypt’s system is anything but democratic. After coming to power via military coup, Sisi’s post-coup government eliminated political opposition by banning them, shut down oppositional television networks, ordered violent dispersals of opposition protests, and issued draconian legislation. Sisi handpicked an interim leader who promptly chose a small group of “experts” to write a new military friendly constitution. The government campaigned aggressively for a "yes" vote in a national referendum on the constitution, while arresting those who campaigned for a "no" vote. The constitution passed in a referendum widely condemned by rights groups, scholars and other observers.

Following the elimination of all serious opposition, Sisi won a sham presidential election with nearly 96 percent of the vote. Most recently, Sisi used legislation to ensure a loyal, rubber-stamp parliament. It is clear that Egypt does not closely resemble a democracy and that no meaningful democratic foundations have been laid. Few outside of Sisi’s circle of ardent supporters will buy the suggestion that a democratic order is emerging. Unsurprisingly, Sisi’s speech was met with Western criticism.

In perhaps the most telling example of the extent to which Egypt’s government is out of touch, an Egyptian military doctor announced in early 2014 that he had cured AIDS, cancer and Hepatitis C with a new medical device that resembled a staple gun. Then presidential hopeful Sisi sat next to Egypt’s interim president at the military-sponsored press conference at which the medical breakthrough was announced. Although no research was published in a scientific journal or presented at an academic conference, the government recognised the cure and reportedly sought recognition from the United States and Europe. Although the Egyptian government ultimately backtracked and went into damage control mode, a full-page advertisement in the current issue of state-owned EgyptAir magazine tells tourists that a “Hepatitis C cure… is just a flight away”. The advertisement instructs tourists to “Go to Egypt” to get cured.

Egypt’s losing propaganda war

The current Egyptian regime lost credibility in many Western circles a long time ago. But recent events suggest that more and more Egyptians are frustrated by the government’s pattern of abuse and denial. Recent protests offer one indication of mounting frustration, while recent Egyptian media coverage provides another.

For the better part of three years, Egyptian media outlets have played the role of obedient lapdog, adopting the official line and avoiding coverage critical of the government. Over the past several weeks, however, typically pro-regime television presenters have been unusually aggressive in their criticism of the government. Amr Adeeb, Wael Al-Ibrashy, Ibrahim Issa, Youssef El-Husseiny, Lamees El-Hadeedy and others have taken turns bashing the government.

More than anything, perhaps, the fresh signs of dissent in Egypt may be an indication that Sisi’s honeymoon phase among supporters may be ending, and that he may be losing the propaganda war he started in July 2013.

Sisi would be wise to heed the voices of international experts. Egypt should cease to push the line that it is the victim of a global conspiracy and, instead, engage in some critical self-reflection. Independent fact-finding committees should be established to investigate atrocities, politicised judges should be dismissed, and fair trials should be held for those suspected of committing abuses.

Moreover, and importantly, reconciliation should be sought with the Muslim Brotherhood and other banned groups, and a national democratic project should be reestablished. These steps could help Egypt avert the violent uprising that some have predicted may occur if the status quo continues for much longer.

- Dr Mohamad Elmasry is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communications at the University of North Alabama.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A screen shows Egypt's President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi delivering a speech during the Africa 2016 forum on 20 February, 2016, in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh (AFP).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.