'I'm being punished': Guantanamo's 'most tortured detainee' still can't leave Mauritania

NOUAKCHOTT - Mohamedou Salahi is beaming. His welcoming smile is a sign that our conversation, delving into his recent past, may not be so excruciating after all.

For 14 years and two months, Salahi was held in Guantanamo Prison without charge, enduring extensive psychological and physical torture, documented in his best-selling book, Guantanamo Diaries.

He was reunited in 2016 with his family in his native Mauritania. Yet sitting with tea, much of his body lost somewhere in the thick white fabric of a traditional robe called a boubou, which hangs off his body like oversized bird wings, Salahi is still not free.

Under pressure from the US, Mauritanian authorities have refused to hand over his passport since he arrived home. He can’t travel for treatment to fix a longstanding nerve condition that he says was exacerbated by his Guantanamo torturers.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

His newborn son in Germany is unable to be formally registered as a citizen because Salahi can’t get there to sign papers. And without a passport, Salahi cannot work or register to vote in Mauritania. His wings are clipped.

Yet sitting at his friend’s place in a relatively affluent neighbourhood of the capital, Salahi is smiling. He sits with one foot on a velvety purple sofa that wraps around half of a spacious living room. He has a greying beard, but appears much younger than 48 with bright, engaging eyes.

Over the course of the three cups of tea, we take in the virtues of YouTube, human happiness and how he gained an inner sense of freedom during his long detention and torture, one that he says can only be reached at rock bottom.

“If you are at the bottom of society, you are not afraid of anything because they cannot do anything to you because you are already at the bottom," he says.

"That’s how prison is. I don’t need to pretend anything. It's freedom in a weird way, freedom of soul.”

Branded a 'high-value' al-Qaeda operative

Born in 1970 in Rosso, on Mauritania's southern border with Senegal, Salahi memorised the entire Quran as a teenager before winning a scholarship in 1988 to study electrical engineering in Duisburg, a port city in what was then West Germany.

He was working for a German technology company in the late 1990s when he came onto the radar of the US intelligence services.

The US had been jolted by attacks claimed by al-Qaeda on its embassies in East Africa, and so stepped up efforts to track suspected militants.

It so happened that Abu Hafs, Salahi’s cousin, was Osama bin Laden’s religious adviser. Two of the men who went on to become 9/11 hijackers had also spent the night at Salahi's house in Duisburg.

US authorities also knew that Salahi had once sworn allegiance to al-Qaeda, and fought against Soviet-backed Communists in Afghanistan for three weeks in the early 1990s, before breaking off ties with the group.

This was at a much earlier time in al-Qaeda’s rise, before the group was considered a threat to Western interests - and a few years after bin Laden and other future leaders of the group had fought on the side of the US-backed Mujahideen to oust the Soviets from Afghanistan.

Salahi must be a “high-value” al-Qaeda operative, US authorities determined in the wake of 9/11 , as they and their allies began to pick up suspected militants from around the globe on the flimsiest of pretexts - a phone call made here, a rumour there - if any at all.

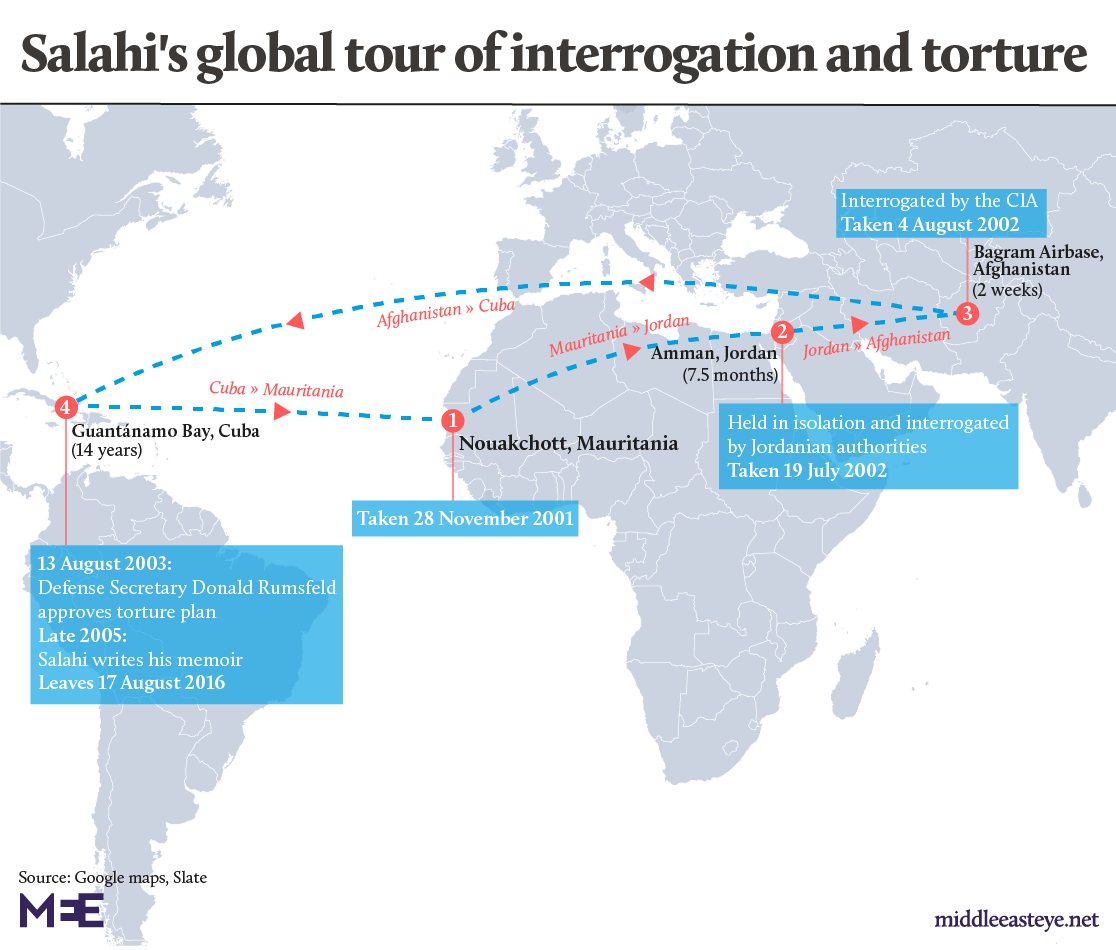

Acting under US pressure, it was authorities in Salahi’s own country, Mauritania, who after detaining him in 2001, turned him over to Jordanian commandos. He was then rendered to Jordan's capital, Amman, where he was held for seven and a half months in isolation before he was taken to the notorious Bagram air base in Afghanistan by the CIA.

After two weeks, he was hooded and bound and put on a plane to Guantanamo, his last stop on a global tour of illegal rendition, detention and torture without trial, which would last 14 years, the effect of which he still lives with today.

'Like I had just stepped from a time capsule'

One of Salahi’s first requests after arriving back home at the start of 2016 was to ask his family to buy him two large TV sets full of channels.

A strict diet of curated news and information fed to him by his US captors had made him hungry to understand what the world was really like.

“We could not know anything except what the American government told us,” he says.

He asked his niece to set up the channels. She looked at him and said “I have never touched a TV in my life” and instead used a smartphone to watch everything.

Realising that the world had moved on and that he was now playing catch up, Salahi said: “Oh God, I'm so freaking old, man.”

Surprisingly, the first things he wanted to do once he got a smartphone were to watch YouTube videos about Guantanamo and listen to songs once played by his Guantanamo guards.

He compared the experience of wanting to recreate Guantanamo in his head without physically being there to watching a horror film.

The thought of still being at Guantanamo offered a strange sort of security in the early days after his release, he said.

“I told myself that in this cell no one is going to kidnap me, because the people who kidnapped me, they already have me," he says.

"If I’m outside of this cell then I’m under the constant threat of being kidnapped again and going through the same pain.”

By the time of his release, his mother and one of his brothers had died, but he had new nieces and nephews.

'I was hurt like never before; it wasn't me any more, and I would never be the same as before'

- Mohamedou Salahi

“I didn’t recognise a lot of my family. People were getting old, and some who weren’t born were now men and women," he said.

"TV wasn’t important at all and now everybody watched the news on the internet.

“It was like I had just stepped from a time capsule and was there trying to fit in.”

Though Salahi continues to vocally demand his rights from the Mauritanian government and the US, he has found it in him to forgive.

“I don’t have beef against anyone. I’ve wholeheartedly forgiven everyone,” he said.

As proof of this, he says he sometimes speaks to his former interrogators, and that under his influence one of his his former guards, Steve Wood, has converted to Islam and visited him in Mauritania.

But it took a long time for him to reach that stage. At first, he says: “I wanted revenge.”

Freedom of the soul

While his kidnapping and detention cut short his aspiration to study further and build his career, it also meant that he was now unburdened from the pressures of daily life, he explains.

“The life many people live now doesn’t allow you to have time to think about anything because we are the slaves of time," he says. "I was like that as well, but then my life was cut short by prison. I had to redefine who I was and my relationship with God.

"I had time to think. All the great prophets, including Muhammad, and all the great philosophers, they went through this process of solitude. It allows you to know who you are. I had to redefine everything, it was a complete life transformation."

Salahi spoke about what it felt like to be “driven to the bottom of society” and how in prison, he had found a "freedom of soul".

Surprised, and a little bewildered by his comment, I reluctantly ask if he found happiness at Guantanamo.

“Absolutely,” he says right away. “It was like an epiphany. One day I was in the interrogation room and that’s when they started to torture me.

"They [the interrogators] were very happy but I was shaking, scared. I was asking myself why I was scared, then it came to me that my expectation that I would be hurt led me to be unhappy and scared.”

He continues: “We have a saying in Arabic, waiting on torture is worse than torture itself.

"I remember many times when they threatened me and I just wanted to get it over with. I would be so eager so that they just did whatever they wanted to do.”

Salahi still has nightmares about being stuck in Guantanamo, a sign that while he was able to find some spiritual space within his torturous constraints, he is not immune from the effects of his treatment.

He says he feels guilty that he has left the camp which still holds some 40 people, and regularly lobbies his lawyers to help them.

Notorious interrogator

Salahi's regimen of abuse was exceptional, and he is regarded by many as the most tortured man in the history of Guantanamo Bay.

The programme of abuse was given the go-ahead from the highest levels of the US government, personally signed off by the then US secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld.

And his torture was carried out by one of America’s most notorious interrogators.

Chicago detective Richard Zuley had made a name for himself extracting confessions from mainly poor black and Latino suspects in Chicago during the 1980s and 1990s.

Some of those who passed through his hands allege physical abuse, manipulation of evidence and coerced confessions.

One African-American women told the Guardian newspaper that Zuley and his team handcuffed her to a wall for over 24 hours in 1994, threatening to not let her ever see her children again until she would implicate herself and her husband in a murder.

A US administration keen to gain intelligence at any cost thought Zuley to be just the man to head up an interrogation plan for Salahi, who they considered to be a “high-value” al-Qaeda operative.

Techniques of rare brutality, rehearsed and refined over decades on the US mainland would now be exported to Guantanamo.

Described variously as “omnipotence tactics”, “degradation tactics” and “monopolisation of perception tactics,” post 9/11 US government documents describe in clinical detail an assortment of techniques designed to “break” detainees, including various types of slaps, stress positions and stripping.

But Zuley’s plan for Salahi surpassed this. Its stated aim was to “replicate and exploit the ‘Stockholm syndrome’” in which a captive victim begins to trust and feel affection for their captors.

A boat trip around Guantanamo

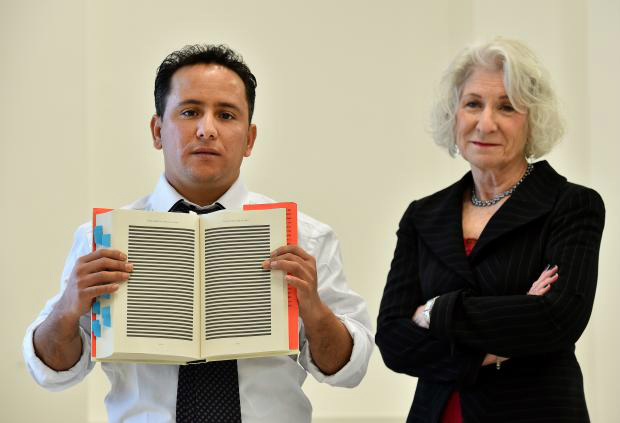

Salahi's memoir, the international bestseller Guantanamo Diary, was written while he was in prison in 2005, but wasn't published until 2015 with numerous redactions by the US government.

In it, Salahi describes being forced to drink water around the clock to deprive him of sleep.

“No sleep was allowed. In order to enforce this, I was given 25oz (740ml) water bottles at intervals of one to two hours, depending on the mood of the guards, 24 hours a day," he says.

"The consequences were devastating. I couldn’t close my eyes for 10 minutes because I was sitting most of the time on the toilet.”

One night, Salahi says he was blindfolded and taken on a boat trip around Guantanamo to make him feel as though he was being taken somewhere else, as dogs barked and guards punched and kicked him.

Three to four hours later, he was left with several broken ribs.

In a memo, Zuley said that he had used dogs to “develop the atmosphere that something major is happening and add to the tension level of the detainee”.

In another case, Salahi was shackled to an eyebolt - a metal loop used to secure a prisoner’s cuffs or chains - and left in a room with music blasting, where he would be soaked with ice-cold water and only permitted to sleep four out of every 16 hours.

A Guardian investigation found that this was a supercharged version of a technique Zuley had used in Chicago against at least three people.

Force-fed during Ramadan

A devout Muslim, Salahi was also forbidden to pray for a year and force-fed during Ramadan, after trying to resist a sexual assault by two women.

“I was hurt like never before; it wasn’t me any more, and I would never be the same as before,” Salahi recalls in his memoir about his ordeal.

'One day I was in the interrogation room and that’s when they started to torture me'

- Mohamedou Salahi

Now he began to talk. He confessed. He lied.

Salahi wrote about the dilemma he faced during interrogations: “But the problem is that you cannot just admit to something you haven’t done; you need to deliver the details, which you can’t when you hadn’t done anything.

"It’s not just, ‘Yes, I did!’ No, it doesn’t work that way: you have to make up a complete story that makes sense to the dumbest dummies. One of the hardest things to do is to tell an untruthful story and maintain it, and that is exactly where I was stuck.”

Guantanamo was a key nerve centre in a global web of intelligence gathering where tampered evidence derived from mistreatment and torture could be used to ensnare others.

Information would come from other inmates, or from those held at the CIA’s network of illicit black sites, secret detention centres around the world, which involved the covert help of at least 54 partner countries.

Implicating another detainee

For many years, Salahi lived with the guilt that he had implicated someone he didn’t know in an alleged crime.

Interrogators had asked Salahi about a Canadian man who was seeking asylum in the US. Under pressure, Salahi says he was forced to lie.

“In the beginning, I was very upset because they started torturing me because another detainee said completely wrong stuff about me and I became very angry with him,” he says.

“But then, when I was tortured, I said completely wrong stuff about someone else. God showed me I wasn’t stronger than anybody.

'But then, when I was tortured, I said completely wrong stuff about someone else'

- Mohamedou Salahi

"It's horrible,” he says in a low voice. “And it lives with you for a very long time.”

After alerting his lawyers, the tainted evidence against the asylum-seeker whom Salahi calls Ahmed was eventually thrown out.

Yet as he began to talk, his conditions improved, and he would come to have a television, computer and be given the chance to tend his own herb garden. Things appeared to be on the up, when in 2010 a US court determined that Salahi’s continued detention was illegal.

US District Court Judge James Robertson stated that the evidence against Salahi was “so tainted by coercion and mistreatment, or so classified, that it cannot support a successful criminal prosecution”.

He concluded: “Salahi must be released from custody.”

But it would take another six years of campaigning and diplomatic hand wringing before Salahi was finally released.

'Best tea in the world'

By now, we are well into our third round of attaya, a frothy mint tea served in miniature glass cups, which Salahi claims is “the best tea in the world”.

Unable to work or travel, Salahi spends a lot of time writing. After Guantanamo Diary, Salahi wrote four more books in detention, but was not allowed to take them with him.

He’s now completed a novel about Mauritanian Bedouin life and is rewriting a book on human happiness that he had already completed in Guantanamo.

Salahi takes a phone call warning him about protests that have sprung up across Nouakchott, disputing the result of the previous day’s presidential election.

Many here distrust the political establishment which has been dominated by the military for decades. Former army chief Mohamed Ghazouani is ahead with 52 percent of the vote and will go on to win.

Videos emerge later that week that show a violent crackdown with police brandishing truncheons and using them against raging protestors.

Cratered streets in poor neighbourhoods are filled with the black smoke of burning tyres.

The protestors in the videos are black, poor descendants of former slaves, who were once the property of the country’s Arab-Berbers, a 30 percent minority which dominates every sphere of Mauritanian life.

'Still being punished'

Tens of thousands of Mauritania’s black population still live in slavery. And there are telling parallels between Salahi's captivity and slavery, especially as it was practised across the Americas, including in the US and Cuba, the Caribbean island on which Guantanamo sits.

For hundreds of years, black Africans were trafficked and forced to work on sugar plantations there in the most brutal conditions.

What then does he think about slavery in Mauritania?

'Anyone who wants to stay in power, they have to serve America first. I think the slogan of our president should have been 'America first''

- Mohamedou Salahi

Salahi is reluctant to address this directly. It's a sensitive topic in Mauritania, considered a bit taboo. Instead, he refers me to a passage in his book that deals with slavery - but not as it is practised in Mauritania.

“I often compared myself with a slave. Slaves were taken forcibly from Africa, and so was I," he wrote.

"Slaves were sold a couple of times on their way to their final destination, and so was I. Slaves were suddenly assigned to somebody they didn’t choose, and so was I.”

Even though he has now returned home to Africa, he cannot leave, and so he has yet to fully win his freedom.

On the day we met, he had already written a letter - in French, Arabic and English, a language he learned in Guantanamo - to the next Mauritanian president, whoever it would be.

In it, he tore into his country’s ruling establishment, describing it as one of a number of “decaying and corrupt Arab systems, where those in power abuse the poor and the oppressed”.

He is certain the next president won’t grant him his passport even though he has never been convicted or charged during his 20-year ordeal.

“None of them will be ballsy enough to say I am going to apply the law. I am a Mauritanian citizen, but we don't have this understanding of the law in this country,” he says.

“Anyone who wants to stay in power, they have to serve America first. I think the slogan of our president should have been 'America first'.”

But inside he says, he is free, and he speaks without fear.

“I accept that the United States should follow and put to trial all the people who are harming their citizens. I agree with that," he says.

"But I disagree with them that if they suspect you, they kidnap you, they torture you, and let you rot in prison for 15 or 16 years.

"And then they dump you in your country and they say you cannot have your passport because you have already seen so many things that we don't want you to travel around the world to talk about. I'm being punished."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.