Jerusalem's Al-Aqsa Mosque: 'The side you've never seen before'

The golden dome of Al-Aqsa sits on top of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount, one of the most sacred locations on the planet and revered by Muslims, Christians and Jews alike.

The compound is the third holiest site in Islam. Built in the seventh century, it marks the spot where Islam believes the Prophet Muhammad ascended into heaven.

Its importance is underlined every year during the Night of Power, the holiest time of the holy month of Ramadan when Muslims believe the Quran was revealed to Muhammad. It was also Islam's first qibla, the direction towards which Muslims pray, before it was replaced by Mecca in the year 623 CE.

Hundreds of millions of followers spend the day devoted to studying and reciting the Quran. And for hundreds of thousands of worshippers, there is no more sacred occasion than spending the night at Al-Aqsa.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The documentary One Night In Al Aqsa, which has its world premiere in London on 2 August, takes audiences on a journey into the compound through the people who live and work there.

The film is directed by Abrar Hussain, who first made his name with the Islam Channel shows Model Mosque – a reality show to find the UK’s best mosque – and Faith Off, an inter-religious game show.

His 2017 documentary One Day In The Haram showed parts of Mecca, Islam’s holiest site, which is only accessible to Muslims, including the daily routines of the workers and life for the millions of pilgrims who arrive for Hajj each year. Hussain turned his attention to Al-Aqsa because he thinks it has been neglected for too long.

“The love for Al-Aqsa isn’t what it should be among the Muslim community,” he told MEE, “so we wanted to make this to boost Al-Aqsa and do something comprehensive for its recognition. When the opportunity to cover Al-Aqsa came, I had to take it because it’s under threat.

“This wasn’t just about the place, it’s also about the people, the workers and the worshippers who live in such difficult conditions under occupation."

'Our aim was to show people a side of Al-Aqsa they’ve never seen before'

- Abrar Hussain, director

As with Hussain’s previous film, One Night In Al Aqsa explores lesser-seen parts of the compound, from the muezzins calling worshippers to prayer to the role of female employees.

“Our aim was to show people a side of Al-Aqsa they’ve never seen before,” says Hussain, “we didn’t just want to regurgitate content."

Choosing to shoot during the Night of Power was a deliberate choice. “We capture the atmosphere, how it feels, smells, how the heat is, we tried to make the film a very immersive experience."

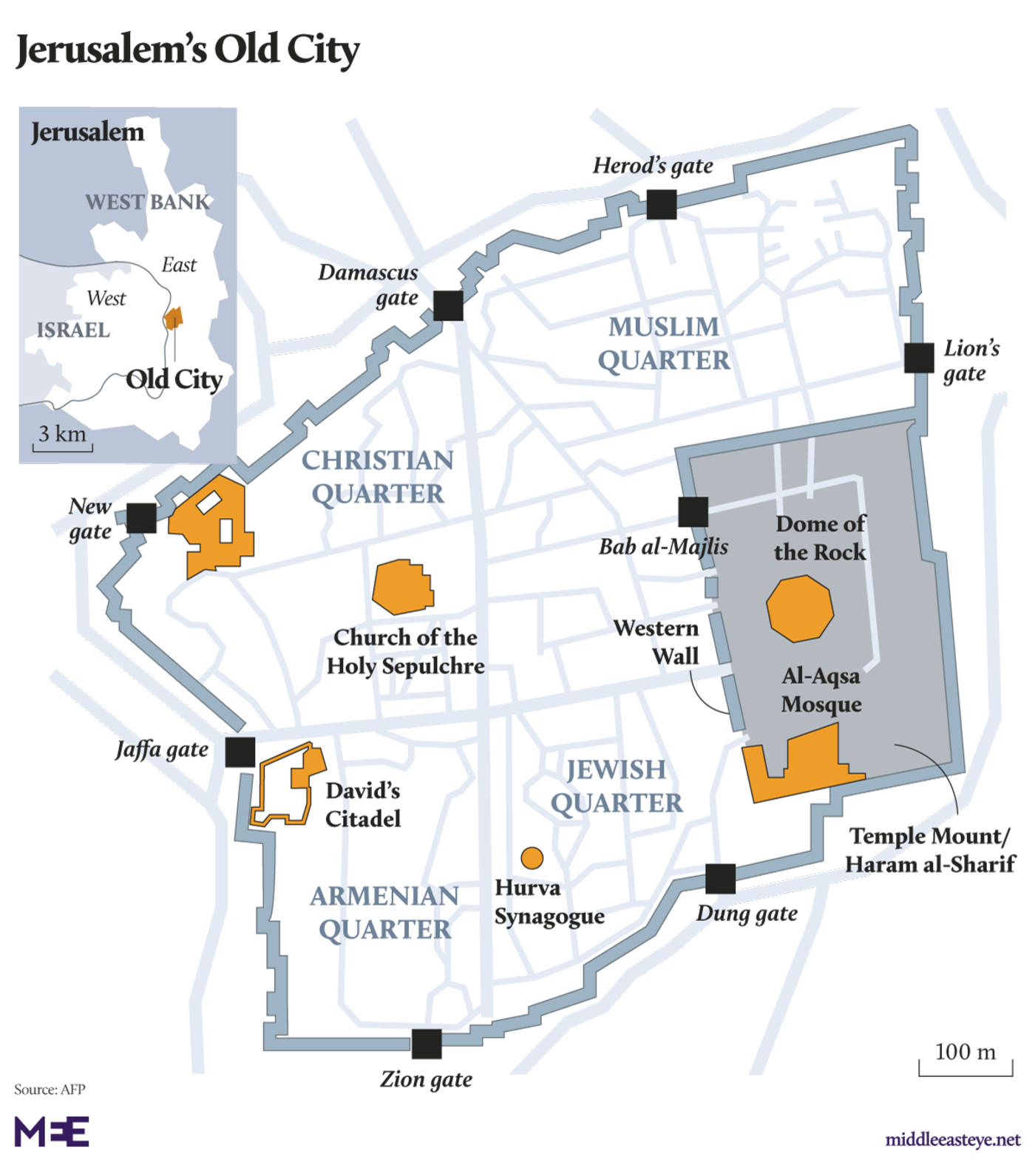

But with its location in the Old City of Jerusalem, Al-Aqsa has been a focus of tension between worshippers and Israeli authorities, who control the complex.

Muslims frequently face difficulties when entering the mosque at Al-Aqsa due to security measures imposed by the Israeli government. Restrictions are often placed on those trying to enter, with entrances being blocked.

Palestinian Muslims in Gaza do not have access to the mosque, while the 2.5 million Muslims in the West Bank can only do so with a permit: restrictions vary, including a total bar on certain days.

This year, for the first time since 2003, Palestinian worshippers were able to pray at the al-Rahma Gate, one of the doorways to the mosque.

From the start, the film team faced obstacles entering the compound and showing parts not seen before in such depth. “One of the major drawbacks was for the last two or three years in Jerusalem they’ve had a complete drone ban," says Hussain, "and as a film-maker I use drones to get important shots that resonate with viewers. I tried our hardest to get permission but couldn’t."

Instead Hussain and his team asked film-makers around Jerusalem if they had drone footage. “Many of them let us use it."

The team also faced questions from guards and Israeli authorities, who also imposed restrictions. “We were operating with a small crew so we wouldn’t attract too much attention to ourselves," Hussain says.

"We were very wary because even with permissions you could turn up at the gate and they would have to check the equipment or x-ray it, so we would take smaller cameras into the mosque and find ways around it."

Getting into the compound was not the only problem the team faced, as Hussain and his eight camera crews negotiated the site, crammed with 400,000 worshippers who had endured intense heat after a day of fasting.

It is little wonder then that Hussain, who was sleep deprived and dehydrated, called Night of Power one of the hardest shoots of his life.

“The whole crew was shattered. We did a Fajr to Fajr [pre-dawn prayer] shoot and it fell on a Friday so we captured jum’aa [Friday congregational prayers]. I’ve worked in some pretty difficult places but that was probably the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.”

Despite practical problems, the shoot also had its emotional side, not least coming after his experience in Mecca.

“I was constantly comparing the two locations,” Hussain says. “When I first went to Mecca, it felt like I had arrived home, or like I should have always been there and I didn't want to leave.

“But when I got to Jerusalem, although I loved it, I couldn’t wait to get out. I felt so constricted there and paranoid about the guards. It felt like I couldn’t breathe there. But just the feeling of walking into the compound, a place where so many prophets prayed, was really quite overwhelming.”

Hussain also says he was upset to see the compound in such a state of disrepair, with lights not working or bits of pavement broken.

“When I asked, I found that it was because for any changes to be made there is a lengthy, sometimes a never-ending process, and permits that are needed."

With One Night in Al Aqsa about to reach cinemas, Hussain is already thinking about future plans.

Aside from inspiring more Muslim creatives (“I’d love to do filmmaking seminars for young people to get them involved in the industry and encourage them to get them into this field”), he is also considering further faith-based content.

“We have several exciting projects that are in development. Alhamdulilah (praise be to God), I’m grateful for that and the trust of the Muslim community,” he says.

“We’ve had these institutions for over 1,400 years and it’s only now that we’re really taking a deep look and exploring it. It’s much needed.”

One Night In Al Aqsa premieres in London’s Leicester Square on 2 August before opening in cinemas in the UK. It will also be distributed in the US, Canada and Australia: more details at One Night In Al Aqsa.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.