Street signs to Sindbad: Uncovering the legacy of Arab graphic design

I had never given much thought to Cairo’s street signs. I liked them, certainly - subconsciously I found a certain charm to their white-on-blue calligraphy and often-stunted English transliterations - but I had never really stopped to notice them.

It wasn’t until designers and scholars Bahia Shehab and Haytham Nawar were presenting their new book A History of Arab Graphic Design, that I learned to do a double-take to their everyday presence.

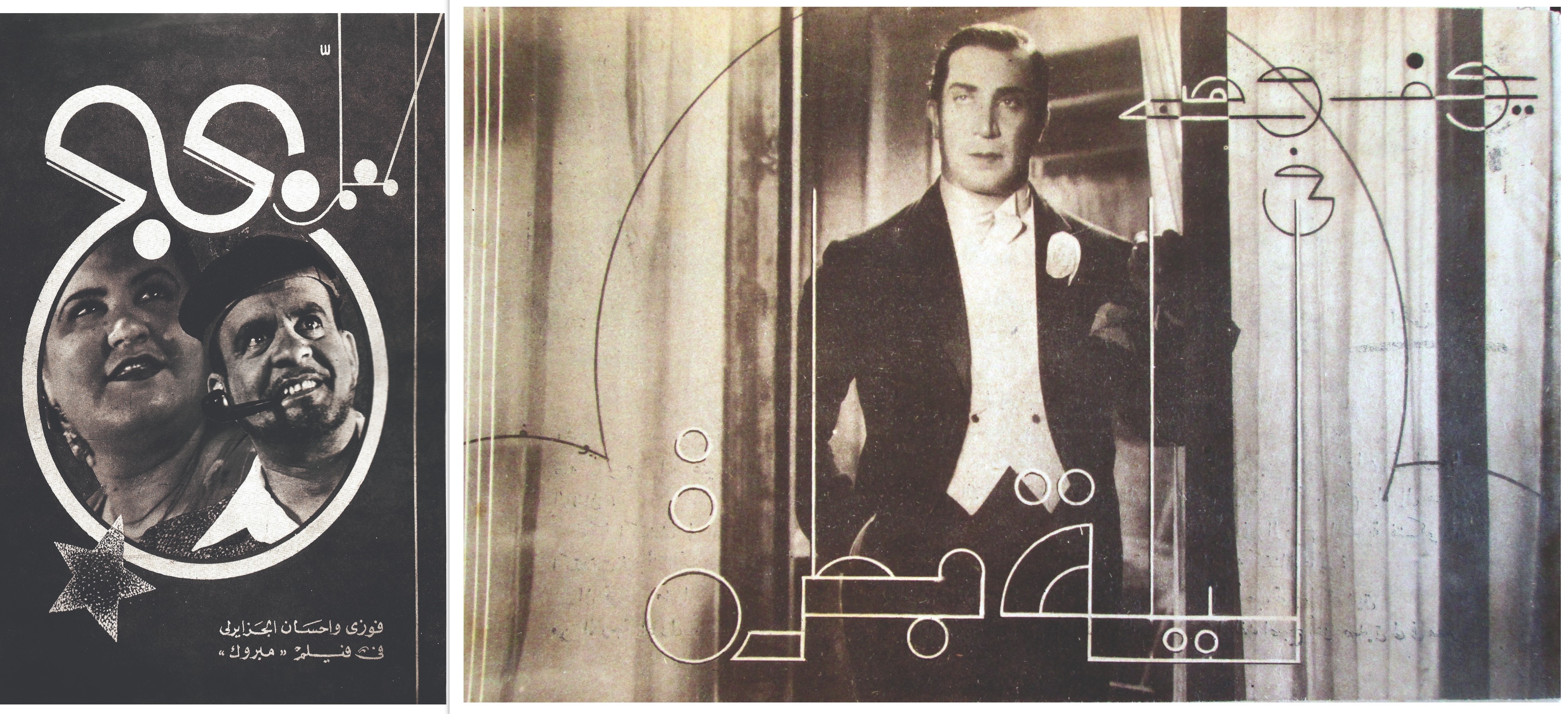

Sayed Ibrahim, known as the dean of Arabic calligraphy, was a pioneer of the early 20th century, and a graphic designer whose work precedes the term "graphic design". In addition to creating the current logo for Al Ahram Newspaper and logotypes for giants such as Om Kulthoum, former president Gamal Abdel Nasser and Prince of Poets Ahmed Shawqi, Ibrahim’s lettering still lines Cairene streets today.

“Before World War One, calligraphy was a more royal art. Calligraphers used to be commissioned for the royal court or to scribe the Quran and other holy texts,” says Shehab of the post-war boom for calligraphers that birthed graphic design in the region.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Now - because of cinema and brands that were emerging after the war - there’s more access to their work for a greater public. Calligraphy started being taken to the streets, to the people.”

By taking a closer look at the design all around us, the everyday is revealed to contain a substantial cultural inheritance

One of the most fascinating aspects of Shehab and Nawar’s book is precisely this: how, by taking a closer look at the design all around us - the omnipresent logos, our childhood magazines, the street signs of Ibrahim in Cairo and Omar Racim in Algiers - the everyday is revealed to contain a substantial cultural inheritance.

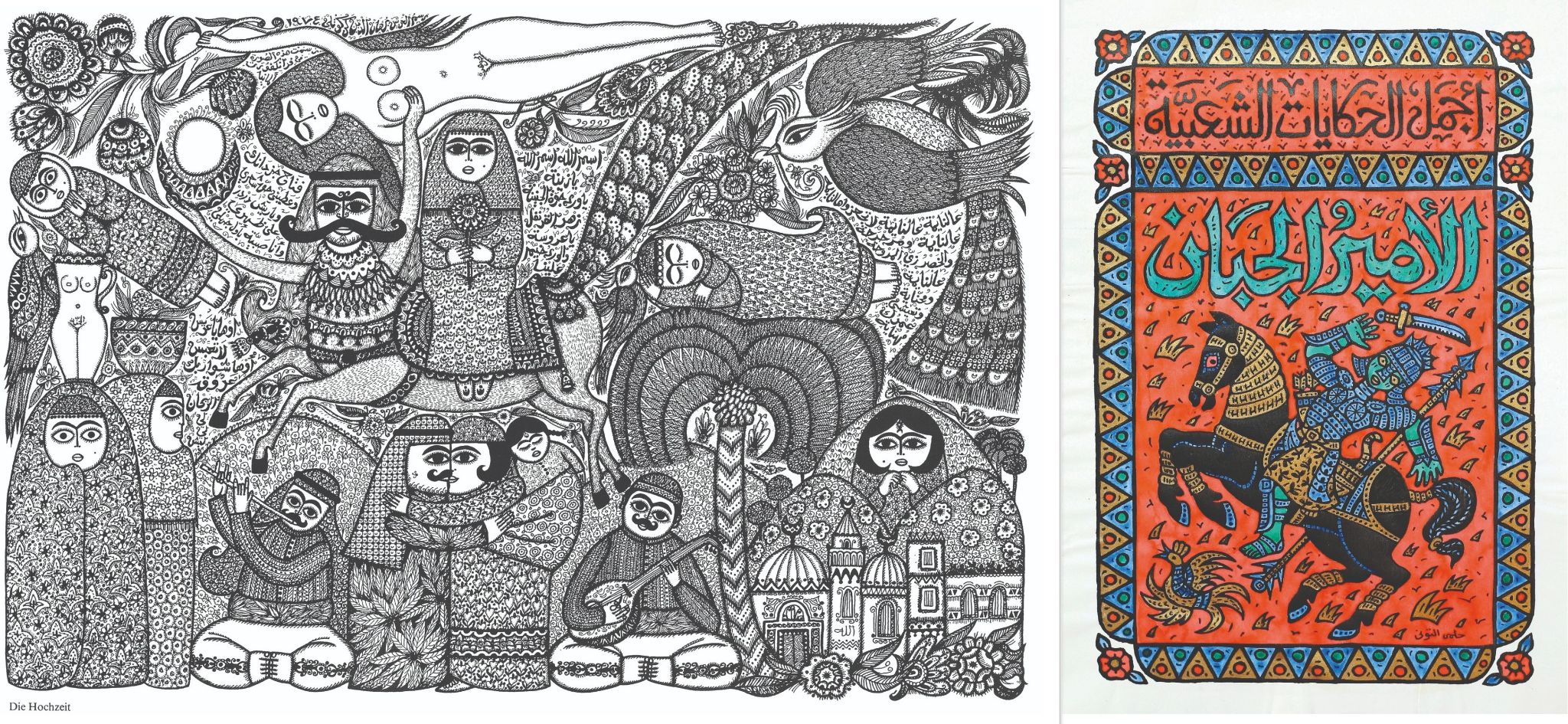

From Islamic manuscripts through the titles of Golden Age cinema to posters in solidarity with Palestine, generations of designers (some we know, many more we do not) have left a rich legacy of Arab graphic design, one we can still see today. In the process, they built unique visual languages that all too often go unappreciated, were it not for projects like this.

The book - a large, 400-page volume that took four years to write - is both narrative and encyclopaedic. Though the book’s timeframe is the 20th century, just barely leading into the 2000s, it is not just a chronology of the 20th century giants of the field. It starts long before the “father of Arab graphic design,” Abdel Salam el-Sherif, started working in the late 1920s, and extends beyond a biographic focus.

Instead it traces (to name only a few examples) the long lineage of Islamic visual language; the evolution of the Arabic typewriter; the negotiations of postcolonial visual identities; the theories behind the motifs of Arab national flags; and the impact of political turmoil on design, all in astonishing detail.

At every point, however, Shehab and Nawar insist that their project barely scratches the surface of the history, that there is far, far more to discover about the people behind the Arab world’s visual culture.

In their prose, at their book launch in Cairo, and in their conversation with Middle East Eye, they reiterate the sentiment behind the book’s dedication: “To the forgotten Arab designers.”

Tracing the lineage

This sense of oblivion, of a history that has faded into the background of our lives, is a bigger issue than my own casual awe at putting a name to the logos around me. Design educators themselves, Shehab and Nawar approached the project as an educational tool, one designed to instil in their students the knowledge that graphic design is not - and has never been - a foreign import into their culture.

“When I was a student at the American University in Beirut, 20 years ago, I was always looking at references from the west that made it look like that is where design originated,” Shehab recalls. “But I was fully aware that we had a very rich, Islamic art tradition that was also very much based on design. So where was that in the global narrative on design?”

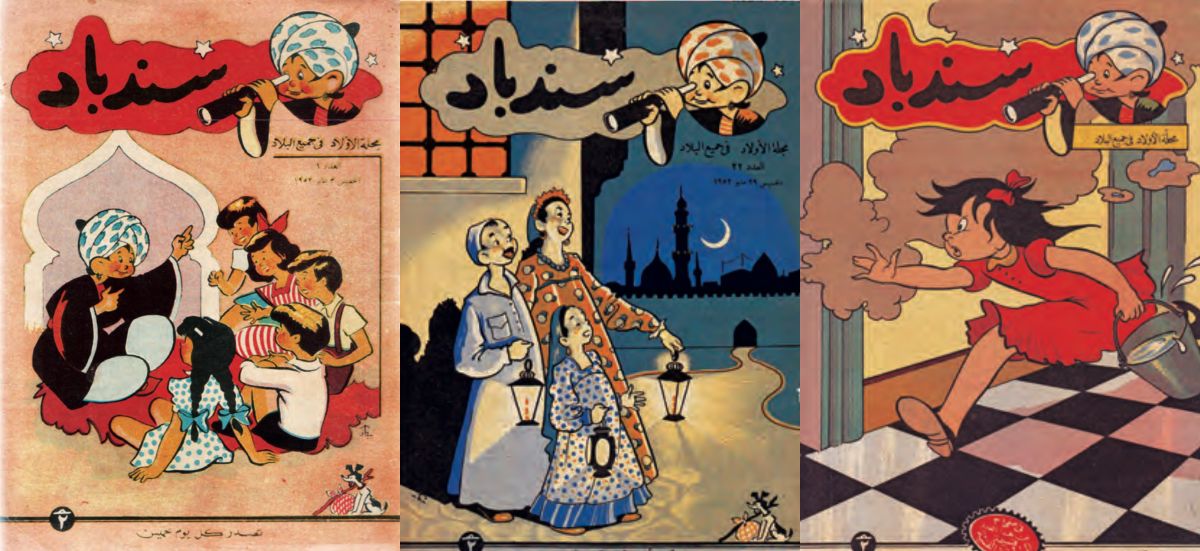

Pioneer children’s magazine Sindbad was so widely read it spurred what came to be known as the 'Sindbad School'

One of the book’s most impactful aspects, therefore, is its tracing of family trees. Not only did these designers work to produce a visual culture; they worked together.

In laying out the history of the field, we can also trace the stylistic and epistemological lines between generations of designers, the conversations they were having across borders, and the schools emerging according to city, style, or beloved children’s magazine.

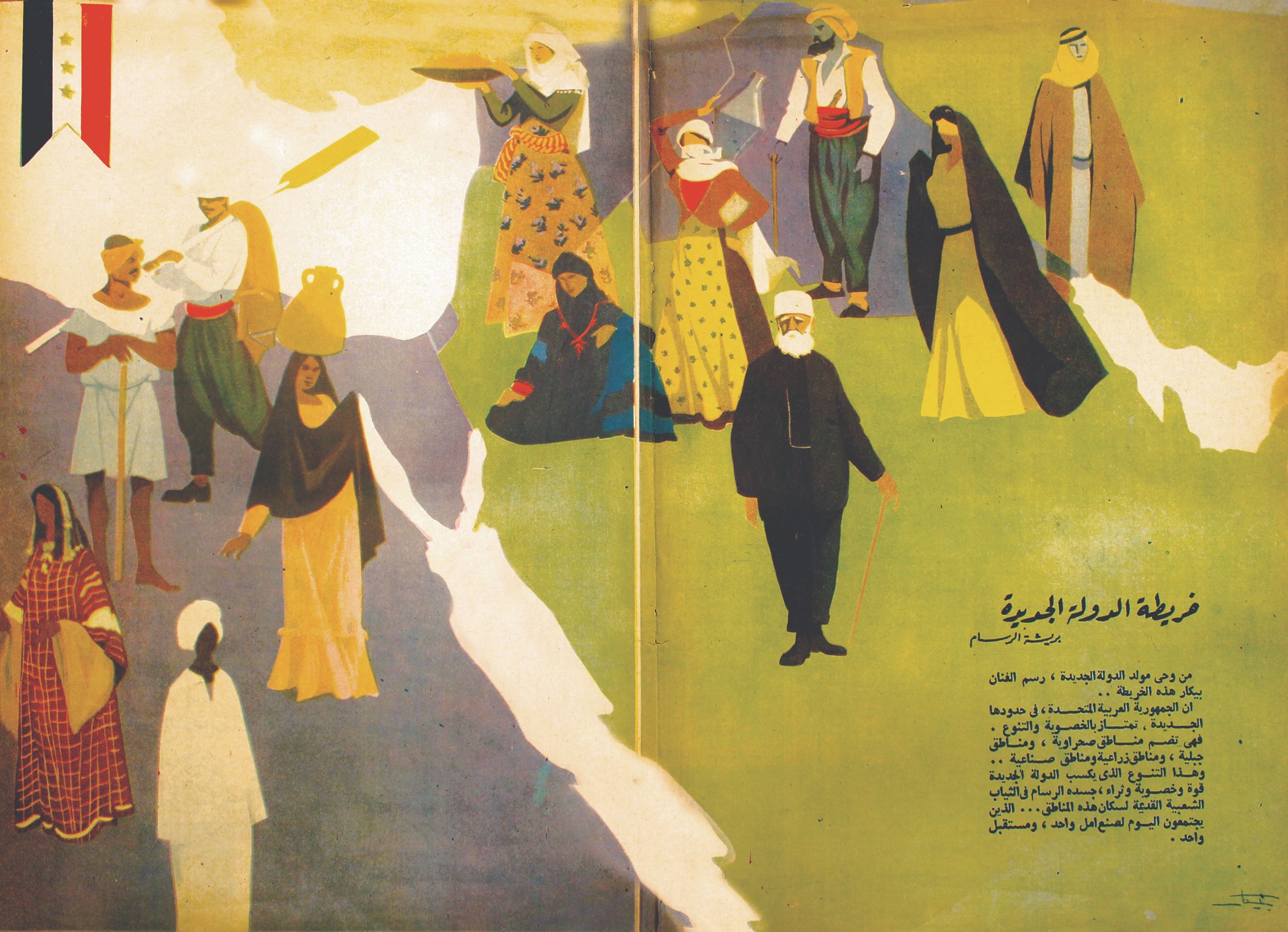

“The first generation of designers, Hussein Bicar and Abdelsalam el-Sherif, they were schools in themselves,” explains Nawar. El-Sherif travelled the region extensively, leaving a trail of proteges in his wake.

Pioneer children’s magazine Sindbad, which ran from 1952 to 1960, was so widely read that, according to Nawar, the generation of artists and designers that grew up influenced by Hussein Bicar’s covers came to be known as the Sindbad School.

In addition to stylistic affinities, and the overarching impact of Islamic art motifs, many of the questions asked by generations of designers were - and continue to be - fundamentally political.

One of the most ardent answers to the question "what do we represent as Arab designers", for example, is continually expressed in terms of solidarity with Palestine, so much so that the fifth chapter of the book is dedicated entirely to the relationship between Arab design and the Palestinian resistance, delving specifically into the world of resistance posters.

Different generations of Arab designers grappled with questions of colonialism and imperialism to different ends. Some, such as Moroccan modernist Mohammed Melehi (1936-2020) and the Casablanca School went to the very root of the issue, inventing tools using henna as a way to decolonise from the paints of the West.

Many more, however, were directly engaged in imagining postcolonial national and regional visions. “Designers aren’t often credited for their role in imagining the past and presenting it to the future,” says Shehab, commenting on Bicar’s work in turn illustrating imaginations of Ancient Egypt and celebrations of the United Arab Republic.

“But they do create the visual language of the period. In Hussein Bicar’s case, this was creating an image of Ancient Egypt in its original colours, and then also one of a unified Arab state, beyond national borders.”

How do we decide what’s worth preserving?

Lebanese calligrapher Kamel al-Baba was a pillar of classical calligraphy. He was in conversation with Egypt’s Sayed Ibrahim, worked tirelessly throughout the 20th century to teach the Arabic script and the evolution of calligraphy, and wrote the seminal work Ruh al-khatt al-‘arabi (The Spirit of Arabic Calligraphy) in 1983.

He was also a prominent commercial calligrapher, designing for example, the masthead for the Lebanese daily newspaper Annahar still in use today. When Shehab and Nawar were searching for his work in Beirut, however, they could not find an archive.

“There was nothing left, even though he was one of the most prominent calligraphers in Lebanon,” Shehab says. “So a part of our research suffered because the kind of work that these calligraphers or designers were doing was not perceived as important because it was commercial.”

According to Nawar, it’s an issue of how graphic design itself is perceived, particularly with the older generation. “People don’t really acknowledge graphic design as a field,” he says. “The generation that is now in their seventies or eighties, very few of them would actually like to be identified as designers. They like to be identified as artists, especially that most of them made art, and then did design as part of their commercial practice.”

More than simply sad - to know that archives like al-Baba’s are forever lost because they weren’t considered inherently valuable - it also brings up an important question: how do we decide what is important, and therefore what is worth preserving? Is a work of design worth less because it’s commercial? Or is it only in retrospect that we can make these decisions?

It’s a question that Shehab and Nawar themselves reckoned with. Despite the book’s encyclopaedic nature, it actually represents only 30 percent of the visual data collected throughout the project. Only able to include a fraction, the pair had to make difficult decisions, and so now sit on an even more expansive treasure trove of material than is in the book.

Many more we don’t know

Although the volume only includes five women designers, the authors see the incomplete nature of the book as precisely the point. It’s a start - and a powerful, seemingly comprehensive one at that - but a start, nonetheless. They point, for example, to the many cases of being told about women designers, but not being able to actually find the material.

Egyptian artist Inji Aflatoun (1924-89), is said to have designed posters while in prison between 1959 and 1963, but nobody has been able to produce her work. A History of Arab Graphic Design, therefore, is also functioning as a kind of siren call to draw out more and more stories and material.

“Already, just at the book launch,” Nawar says, “we had someone come and tell us that their grandfather was actually one of the earliest calligraphers in Sudan, and he has material to prove that his grandfather wrote the street signs and shop signs in Sudan, 70 or 80 years ago.”

As Shehab and Nawar continue to add designers and material to their ever-growing archive, they’re also now working on the Arabic translation of the book - news that the pair were excited to share with Middle East Eye as critically important to making their research available to the audience it matters most to.

“Currently, using Arabic in the graphic design field is very difficult, even for the new generation,” Nawar says. “So part of our mission in translating the content is also translating graphic design terminologies, trends and schools. And you can imagine how beneficial that would be - not just for the history of the field in the Arab world, but the field itself.”

A History of Arab Graphic Design is available now through AUC Press

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.