Arab comic artists discuss adversity and censorship

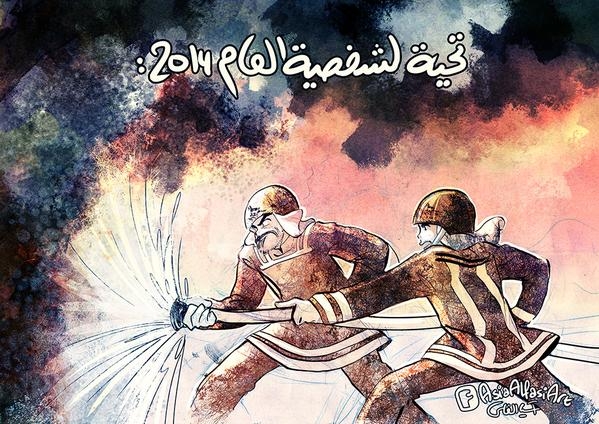

As the only veiled girl in a Glaswegian school, Asia Alfasi did not have an easy time growing up until the Libyan comic artist discovered Manga and began drawing the comics herself.

"It was the first time that people stopped bullying me and were actually interested in what I was doing instead. They started sitting next to me quietly as I drew. It was at that moment that I realised the power that comics have; that an art form can completely subdue a monster and make them receptive. That's when I decided to become a comic artist," Alfasi said at a panel on Arab comic art at the British Library as part of London’s 2015 Shubbak Festival.

The July festival, which aims at promoting contemporary Arab culture in London, featured literary heavyweights such as Mourid Barghouti and brought together a diverse selection of acclaimed Arab comic artists. Lena Merhej from Lebanon, Tarek Shahin and Mohamed Anwar, both from Egypt, and Alfasi spoke on the panel chaired by Paul Gravett, a co-curator of the 2014 ‘Comics Unmasked’ exhibition at the British Library – the largest comic book exhibition in the UK.

As co-founder of the award-winning comic series Samandal, Mehraj said she spent her childhood exploring her imagination and relieving her boredom by looking at books with her siblings.

"We looked at atlases and history books to travel, and we used a cupboard to go to the moon," she said. These exercises in imagination, along with her being, in her own words, "an angry teenager" led to her drawing comics and co-founding the adult comic series in 2008.

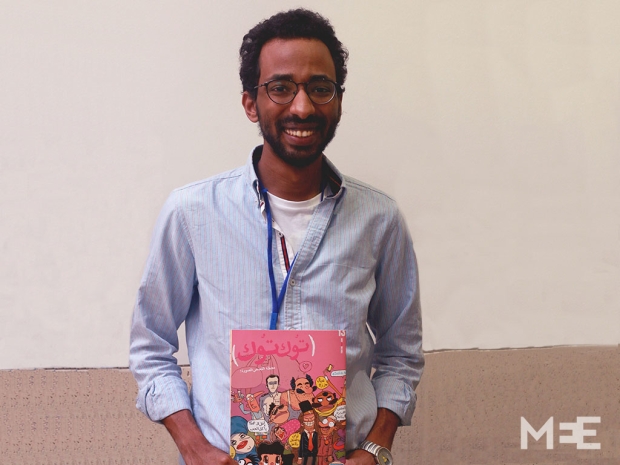

As a contributor to Toktok, Egypt’s first adult contemporary comic series, Mohamed Anwar spoke of his pride in representing the series on the panel, after his peer Andeel had to cancel due to visa issues.

"I think [international interest] in Toktok is testament to our success as a team," he said after the panel. "It is one of the elements that revived interest in comics in Egypt. We were the first to make good quality, professional comic art for adults. Now the next phase is turning the project into an industry."

Sustainability was cited by Mehraj, Anwar and Shahin as a challenge to their comic art. The three artists say they are stretched thin, having to multitask as producers, distributors and promoters of their comic books while working full-time jobs.

"We need to make this industry sustainable," Anwar explained. "We can't continue to rely on grants, we need to find someone to handle the business aspect, and we need to make this a stable industry."

Mehraj, agreed - telling the panel that the number of copies printed of her comic had more than halved since it first went to press.

"The [comic] market in Lebanon is very small," Lena said. "The first issue we printed, we made 2,500 copies, now we're down to 1000, not more. But if some entrepreneur could take over the distribution, we could reach the Middle East. We are all artists; we can't be everything. Right now it's an NGO, we don't make money out of it; we need someone who can make it into a business, and I think that's the case for all Arab artists around the world."

For Shahin, the solution to a contracting industry was to take on all the different publishing roles - but this has come with its own issues.

"I decided to publish independently, so I also do marketing, PR, and distribution, and I don’t think I do it very well, so the lack of a business aspect to this industry affects me as well," Shahin said. "I think comic art is an industry worth investing in, but [there is] no guarantee of a return on profits any time soon. If someone were to invest, they'd have to be a bit charitable and patient at first."

Self-censorship

Gravett led the panel with a brief introduction to the history of Arab comics. The earliest comic was reportedly published in Egypt’s al-Awlad magazine in 1923, with both Egypt and Lebanon dominating the industry throughout the 1950s and 60s. The issue of state censorship was also briefly discussed. Famously, Egyptian author Magdy al-Shafee was convicted of offending public decency in 2008 and his comic book Metro was banned in Egypt, while Syria’s Ali Farzat was kidnapped and beaten in 2001, apparently for his anti-Assad cartoons.

While none of the panellists had similar experiences, Anwar said he recently faced a bitter backlash from his colleagues at the state-run Roz al-Youssef magazine after he made a cartoon of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. Such was their vitriol that their complaints gained enough momentum to reach the media and even the presidency, but without any repercussions for the artist.

"For me, what was extraordinary was that this action didn’t come from the government; it came from fellow journalists," he said after the panel. "I think they did this because of the country’s current state of mind. These are the people that we have to talk to now [as artists]."

Nonetheless, he views the incident as just another necessary challenge to overcome.

"It's not their problem, it's ours. We [artists] must build channels of communication and figure out how to connect with these audiences."

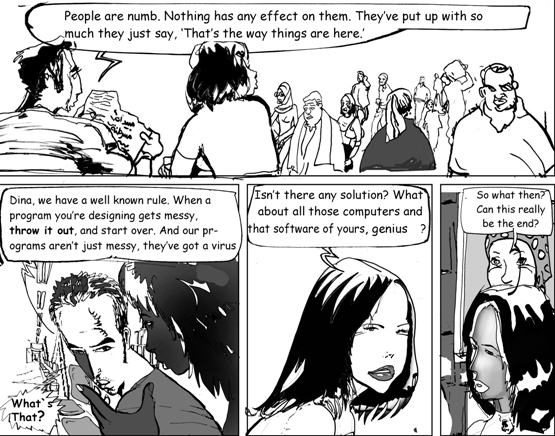

Shahin said he chose self-censorship and subtlety as a means to avoid being persecuted in Egypt for his political cartoon series al-Khan, which appeared in the publication Daily News Egypt until 2010.

"None of my work was ever censored [by the state] but not for lack of trying by the powers that be," he said. "Credit goes to my editor, who always fought on my behalf. I just didn't want to give them excuses to arrest me, and that was a reason for my series' longevity."

For her part, Mehraj brought an academic perspective to the discussion, citing the recently launched Sawwaf Arabic Comics Initiative at Lebanon’s American University in Beirut, which will study, archive and promote Arab comic art. She also spoke of the need for more academic work on the emerging industry.

"Hopefully [the initiative] will engage people in research around comics," she said after the panel. "Because we don’t have any critical work around comics; we have production but we don’t have any feedback."

Perhaps the event's weakest point was the issue of translation: the panel spent considerable time attempting to translate Arabic comics – and Arabic humour – to a predominantly English-speaking audience, often laughing among themselves when the joke was clearly lost on others.

Redeeming this issue, however, was Alfasi's talk of her comic series Juha, and how her research of this Islamic folk tale character led her to discover that Juha, or Nasruldin as he’s known in other parts of the world, also existed in folktales in Iran, India, Russia and Turkey.

"This led me to thinking, instead of importing cartoons and artefacts of culture, why can't we export our own stories [as Arabs?]" she said. "And who better a character to export than someone that ties all of us together? It doesn’t matter who calls him what, but that we all have him in our collective cultures."

Her desire to bridge cultures is also evident in her upcoming graphic novel, to be published by Bloomsbury in late 2015, which is based on her childhood in Libya as well as a year spent with her grandmother in Tripoli during the 2011 Libyan uprising.

"I wanted to give an insider’s perspective to what’s happening in Libya," she said. "My biggest goal here was to humanise Arabs and people in the Middle East. There are so many shared struggles and so many shared stories that everybody can relate to."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.