Reading our own stories: Boom in Arabic children's books

AMMAN - Taghreed Najjar was a teenager when she started creating stories. A voracious reader growing up in a Jerusalem boarding school in the 1960s, her first tales were fantastical narratives about her three-year-old brother, told to her younger siblings. They took on a life of their own, and soon Najjar was compelled to commit them to paper.

“Back then we didn’t really have any authors or writers that I could look to,” she told Middle East Eye. “It was very, very hard, especially in Jordan. There were no artists illustrating anything for children and printing presses were not technically oriented for things like that. It was still black and white because that’s cheaper. It was uncharted territory.”

In those days, Najjar said, there was little in the way of quality, original children’s books for Arabic audiences: the market was dominated by imports from the West, English language books that were more often affordable and highly valued by parents. But in the last 10 years, the industry has experienced a dramatic burst of energy – so much so that insiders are talking of a renaissance, or Nahda.

Publishing houses like Kalimat, which has produced more than 155 books since its 2007 beginning, and Asala, founded in 1999, have garnered powerful reputations for producing great children’s writing.

Awards such as Etisalat, now in its fifth year, are giving creators even more reason to make outstanding work. And nearly 40 years after her first book, Najjar is regarded as a pioneer, a decorated author of dozens of books and the founder of Al Salwa, one of the best children's publishing houses in the region.

“If it’s not a renaissance then something is going on, and it’s been going on for the last seven years,” Rania El Turk, a new Jordanian writer, told MEE. “People are increasingly more interested in getting their children not just to learn Arabic but to love Arabic. And I think there is a lot more interest in getting kids to experience quality books in Arabic, too.”

Turk’s debut Ayn? (Where?) is a simple story about searching for a ladybird, the first wordless, lift-the-flap board book in Arabic. The idea evolved from Turk’s observation that tactile, wordless books that were culturally relevant – in settings familiar to children in Jordan, with Arabic snippets in the pictures – simply didn't exist. It was jointly inspired by Turk’s work in educational programs in Beirut, where she observed that illiteracy among mothers and a lack of knowledge of Arabic books was preventing kids from developing a healthy attitude to reading.

“There isn’t enough awareness among parents, even among parents who read,” Turk says. “We don’t have lists for the Arab world, like 50 of the greatest books to read. I think we’re still too busy filling gaps to start creating awareness.”

Turk hasn’t been the only person to notice this. Rana Dajani, a molecular biologist by training, says a lack of interest in quality kids’ literature is largely because parents in Jordan rarely read aloud to their children. The realisation prompted her to establish We Love Reading, a grassroots initiative that enables women to create reading groups for children in their neighbourhoods.

“Before the books that were available were not colourful; the topics were very mediocre. But in the last 10 years there’s been a huge bloom of children’s books in Arabic,” Dajani says. Continuing the trend, she believes, depends on creating an atmosphere where reading is valued, for pleasure rather than just instruction. “When we have a culture of reading, children will demand a book rather than a toy. What we’re injecting is a culture of reading, that reading is fun, so this will be reflected on people purchasing books.”

So far, We Love Reading has established 300 libraries in Jordan and directly impacted 10,000 children. Jordanian writers like Najjar and Abeer Taher El Turk, whose most recent book A Very Naughty Cat won the prestigious Etisalat Award, have praised the project. Investment in a love for reading among kids, they say, is crucial for publishing.

Still, problems remain. For Abeer, investment in training for both writers and illustrators is an issue, and finding the right artists to visualise her stories has been a challenge. “To have good writers you need a course in the university, writing for children, and illustration for children,” she says. Nothing of the sort exists in Jordan and, while there might be plenty of great artists in the country, drawing for a young audience is a rare talent that takes time to develop.

When Najjar started out she had the same problem, and though she’s not an artist, even illustrated her own work. Her breakthrough, however, came during another resurgence in children’s publishing, when her scripts were accepted by Dar el Fata el Arabi in 1976. A revolutionary force – in every sense of the phrase – in Arabic children’s literature, the Palestinian publishing house was founded in 1974 by Yasser Arafat and worked from Beirut to produce children’s books that advocated for the Palestinian cause, as well as on less political topics.

“Dar el Fata were everywhere. They were unprecedented, they managed to speak to the whole of the Arab world and their print run was ten, fifteen thousand – you don’t see that even today,” Najjar explains. “But that wasn’t the point. The point was that they produced books. Excellent-quality books in terms of content, in terms of design and illustration, that people here in the region had not seen before or experienced, except for foreign books.

“The message here was clear: that Arabic books can be just as good, if not better. To say, look, we can do that.”

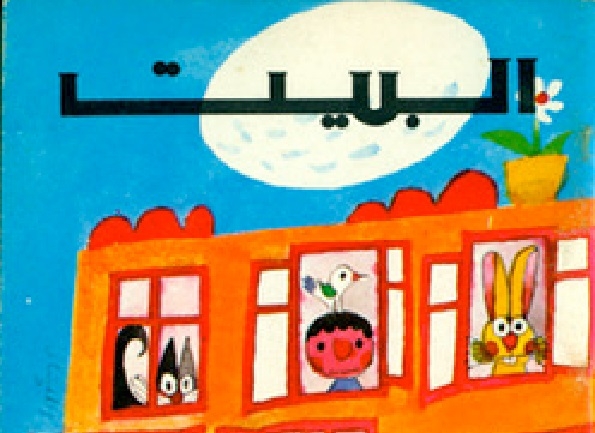

Classics produced by Dar el Fata included Zacharia Tamer’s Al Bayt, which followed a simple narrative. All animals have a home – the chicken has a coop, the rabbit a cave and the fish the river – but the Palestinians do not. Their homes had been taken from them by their enemies, the book said: return to them would be made possible through fighting an armed struggle.

The explicit politics of Dar el Fata were crucial to its success – the Palestinian message united the Arab world. But some writers and artists say it also contributed to its decline, restricting the freedom of creatives to write what they pleased. By the 90s, the publishing house had been closed. Still, its success had created something important: a distinctly Arab identity for literature in an environment that had been flooded by foreign books to a perhaps troubling extent.

“For a long time the books children saw and the people in the books related to foreigners. The houses looked different to our houses, the policemen wore different uniforms, and even the features of the people look foreign. No matter how good the books were they could not relate completely to them,” Najjar said of the books that were available in the 70s and 80s.

“Taking into account the British Mandate, occupation and so on, there was this kind of relationship between the ruler and the ruled, the colonial part of it. That kind of emphasised it, when the books we read, the books we studied, were produced by our previous masters, our previous occupiers.

“For me when I started to write I was thinking of all these children who don’t read, who don’t like Arabic books,” Abeer El Turk said. “And one of them is my daughter; she didn’t like Arabic books. She read English stories, because there were no good stories in Arabic.” The observation – and the realisation that her daughter’s Arabic was suffering as a result – compelled Abeer to write books that were fun, entertaining and in Arabic, that wouldn’t force kids to look to English books for work they loved.

Still, for those shaping the new landscape of Arabic children’s literature, creating great work in Arabic comes with profound challenges. In a region so torn by conflict, distribution is a serious one, and war means it’s virtually impossible for books to reach Syria and other areas. Rania El Turk, too, is conscious of censorship when finalising her books – standards of modesty, for example, are a consideration when it comes to marketing to the essential Gulf market.

Quality picture books are also expensive by nature, and public libraries for lending books don’t have a particularly strong foothold in Jordan: even when they’re available in Sweden, Japan and the USA, she says, Najjar’s books are nearly impossible to find in more distant Jordanian towns like Ma’an or Aqaba.

Writers and readers are agreed that if the renaissance in publishing is to continue, there’s much more work to be done. But after decades of Jordanian markets being filled with English books and translations, traffic is beginning to move in the opposite direction: Najjar’s book Why Not? was translated to English by Lucy Coats last month as The Little Green Drum. Set in the village of Lifta in 1930s Palestine, it tells the story of a young girl who takes on her father’s role of waking the village up during Ramadan Suhoor.

“I realised that if I wanted to become a writer, then I needed to be an authentic one,” Najjar says. It wouldn’t be enough to place tokenistic cultural referents or familiar settings on her pages, she realised. Her task would be to create an original voice on her own. “I couldn’t be a photocopy. Because if I was a photocopy of foreign literature then I would not have any value.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.