Stones, masks and matches: A decade of Middle Eastern art

The British Museum’s Islamic and Contemporary Middle East art curator Venetia Porter has authored a new book, Reflections, showcasing the museum’s collection of contemporary Middle Eastern art. Key works added to the museum in the last decade include artists’ responses to the Arab Spring and its aftermath. The Flag, by Mohamed Abla, evokes the exhilaration of the occupation of Tahrir Square in Cairo in 2011 (Reproduced by permission of the artist, Mohamed Abla)

Since 2009, the British Museum’s Contemporary and Modern Middle Eastern Art acquisition group (CaMMEA) has been acquiring work for its collection, drawing on the extraordinary creativity of artists from the MENA region. Many of the purchases appear in Porter’s book. They include the Syrian digital artist and filmmaker Sulafa Hijazi’s Untitled, 2012. Hijazi began her career by sharing her digital images on social media (Courtesy of Sulafa Hijazi and Malu Halasa)

Last month the museum’s former director, Neil MacGregor, revisited his popular 2010 BBC radio series A History of the World in 100 Objects. He added his 101st object: Syrian-born Issam Kourbaj’s Dark Water, Burning World, 2017, where Kourbaj used matchsticks and bicycle mudguards to represent frightened, huddled groups of refugees fleeing in precarious boats. “Kourbaj’s little convoy of matchstick figures stand for all migrants, anywhere, driven by fear, and guided by hope,” MacGregor said (Courtesy of Issam Kourbaj)

Revolution and war in Syria was the backdrop for work such as Azza Abo Rabieh’s Our Revolution is on the Boot of Our Government, 2011. “A common question has been why the work of so many artists of the Middle East is often overtly political,” Porter writes in her book. “It is of course far from the case that all work made by artists of the Middle East is political, but it is nevertheless a distinct feature.” (Reproduced by permission of the artist, Azza Abo Rabieh)

The Egyptian-born artist Khaled Zaki, however, deliberately chose to begin work on his sculptural project The Sufi in 2012, shown in the Egyptian pavilion at the Venice Biennale, at a time when the Middle East “was burning with confrontations”, he said. Zaki's sketches for the work address a doctrine encouraging peace and forgiveness (Reproduced by permission of the artist, Khaled Zaki)

There is a strong history of modern artists of the Middle East responding to political and social upheaval. Lebanon’s Paul Guiragossian in La misère humaine (Human Misery) reflected the mass expulsion of Armenians from Turkey in 1915–16, whose survivors included his own parents. These grim black figures were described by one curator as “mute witnesses of history”.

“Through art’s power to speak directly to human sensibility, artists can draw attention to the price - in terms of human lives and suffering - that political decisions can inflict on the citizens whom governments hope to mobilise,” MENA region expert Charles Tripp writes in an essay for the book (Courtesy of the Paul Guiragossian Foundation)

The work of Palestinian artist Hazem Harb is “utterly informed” by the politics of Israel and Palestine, Tripp adds. “I have a mission in my life, with my artwork,” the Gaza-born Harb declares. His work from the series Beyond Memory is typical of the artist in drawing on archive material to create a sense of loss and longing. Here he superimposes period images of men boating on to the background of the separation barrier (Reproduced by permission of the artist, Hazem Harb)

In Untitled, 2011, Djamel Tatah presents an image of a boy offering handfuls of stones; it speaks immediately of Palestinian resistance, though Tatah is a French-born Algerian whose work often draws on newspaper images from across the region, of people living in conflict zones.

The focus of Gaza-born Palestinian artist Taysir Batniji’s work is exile and displacement. He last visited Gaza in 2012 and has been unable to return; in travel documents, he has seen his nationality stamped “undefined”. The artwork in the top image, in aquarelle on paper, perhaps shows the figure of the artist himself, contemplating life in a suitcase (Reproduced by permission of the artists, Djamel Tatah and Taysir Batniji)

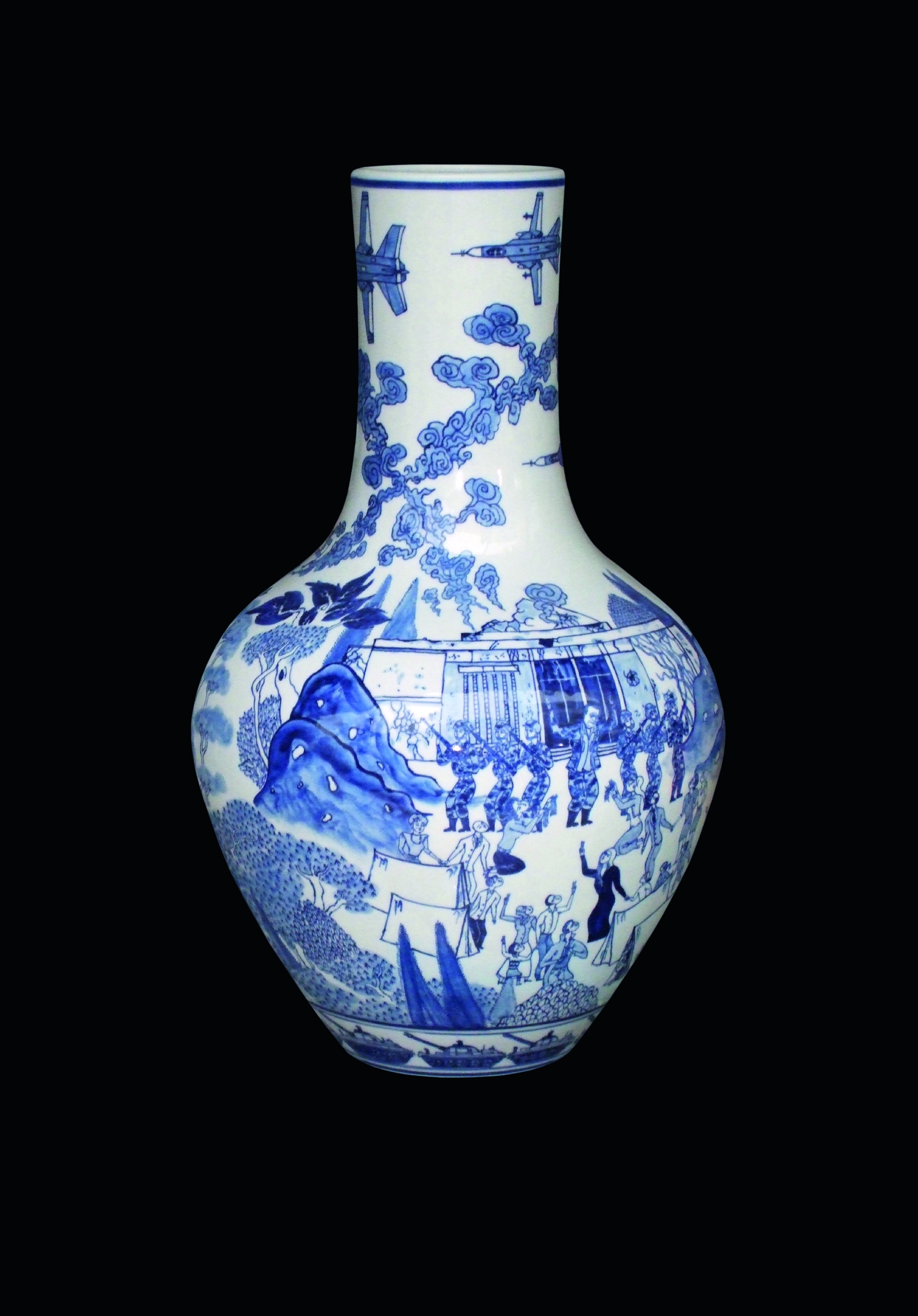

Beirut-born Raed Yassin portrayed key events in the Lebanese Civil War on seven porcelain vases, recording battles as the Ancient Greeks had done, to challenge what he called “uneasy amnesia” about past conflict. His Yassin Dynasty, 2013, showed the unsuccessful “War of Liberation” launched by then General Michel Aoun at the end of the 15-year war (Courtesy of the artist and Kalfayan Galleries, Athens)

Reflections was published to coincide with an exhibition of the same name opening soon at the British Museum. With more than 100 works, it was due to open its doors on 11 February, but it has been delayed amid the coronavirus lockdown; Venetia Porter will give a (virtual) curator's talk on 25 February. While The Flag by Mohamed Abla is in the book, but not in the exhibition, his work In Conversation (above) will be shown (Reproduced by permission of the artist, Mohamed Abla)

Reflections is available from British Museum Press

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.